You’ve driven by it a million times: the reddish brown brick building on the northwest corner of NE 24th Avenue and Stanton. As I’ve researched this building and its history over the last two years, I’ve spoken with neighbors who’ve thought it was once maybe a school, a brewery, a home for wayward youth: all understandable given its institutional look and size.

Originally referred to as the Garfield Telephone Exchange, or the “Garfield Office,” this building is still functioning today for its original purpose: making sure telephone calls get connected to the right place at the right time.

When it went into full operation in 1924, the building housed telephone operators at switchboards plugging incoming and outgoing calls to and from individual circuits that served homes in Irvington and Alameda. One operator remembered that some of her colleagues and supervisors wore roller skates to help them move quickly from switchboard to switchboard.

Today, the hallways and rooms are quiet except for an omnipresent electrical hum, the quiet clicking of switches doing the job of the former operators, and the soft buzz of fluorescent lights. No roller skates, no operators, in fact it’s uncommon to find anyone in the building at all anymore.

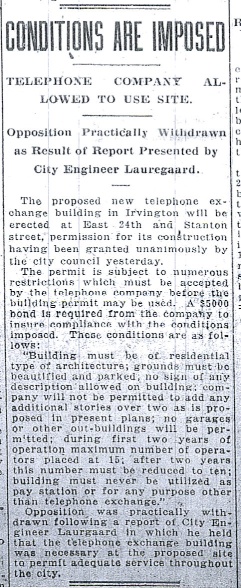

Pacific Telephone and Telegraph Company first rolled out the need for a telephone exchange building in 1919, and chose the location at NE 24th and Stanton because of its strategic location in this growing area of Portland. But early residents did not like the idea of a semi-industrial/commercial building being located in the heart of a residential neighborhood. Building codes and land use ordinances at the time were permissive and allowed the project to move forward. But influential residents of Irvington petitioned Mayor George Baker and Portland City Council to tighten restrictions, which they did on January 14, 1920, throwing a monkey wrench into project planning for Pacific Telephone and Telegraph.

Engineers for the company were stung by the new restrictions—which allowed residents to object to projects—and complained that the new public involvement processes were going to set back development of the new technology.

The Oregonian reported on January 15, 1920:

The action of the city council yesterday, according to W.J. Phillips, commercial manager of the telephone company, will upset the entire plan of development outlined for the next 20 years in Portland…he fears that the entire future service may be impaired.

Forced into reckoning with the neighborhood, the telephone company reluctantly agreed to work with a committee of neighbors to refine designs for the telephone building. Noted Portland architect A.E. Doyle, an Irvington resident, helped lead the committee and eventually won design restrictions which were reported in the April 15, 1920 edition of The Oregonian as follows:

With these restrictions in place—and with designs emerging that showed the attractive architectural details we see today—the neighborhood dropped its opposition and the project proceeded. Building permits were issued and construction followed, completed by Portland building contractor J.M. Dougan and Company at a cost of $123,690.

Trying hard to reach out to the community with a message of progress, Pacific Telephone purchased an advertisement in The Oregonian touting the new facility and mentioning the $1 million total project cost, which included the complicated and costly miles of phone cable buried throughout the area that culminated at and connected into the building.

As Portland’s housing boom produced more demand for phone service, complaints began to mount against Pacific Telephone and Telegraph about the speed at which they were responding to the growing need. In several news stories in 1921 and 1922, phone company officials were quick to point the finger of blame for these complaints at the Irvington neighborhood for slowing down progress on the Garfield Exchange and causing a ripple effect of delay throughout Portland. The building finally went into full operation in January 1924.

Even after construction, and the cables installed, residents still needed to be trained how to use the new phone equipment. The blizzard of news stories about the Garfield office and the Irvington delays (more than 15 news stories on the subject from 1920-1924) finally quieted down in late 1925 when everyone settled into using their phones, and trying to keep up with the changing technology.

Several minor additions have been made over time, and obviously complete technical overhauls have been made inside. Two houses to the north of the building were razed to make room for today’s parking lot. Despite these changes, the conditions outlined in the 1920 terms pretty much hold true today.

The building has a roof that can withstand a WWII bombing attack…part of history.

Tell me more… It is indeed a sturdy terra cotta-looking tile.

When I chatted with folks that worked there when they did a remodel, I was told that the “roof” is six inches thick concrete. Then it has decorative elements. It would have made sense to protect targets as we were paranoid in the WWII days. Oregon is the only state to have had two attacks then–submarine over at the coast and balloon bombs to the forests, but only the balloon bombs actually killed anyone. Or maybe someone actually designed it that well from the start. I do know that the area is a sand bar, so it is not the best building for an earthquake, (I had there place right across the street and sand is there deep in the soil.)

I remember going on a tour this building when I was a Boy Scout in the ’50’s. It was fascinating. While you say that today there is a “quiet clicking of switches”, the thing I recall most was the loud clicking of switches and relays. We could actually watch them, too. They told us that each click represented a call starting or ending. It sounded like a telegraph office on a very busy day.

I also did a field trip when I was a probably second or third grader at Alameda School in ’58 or ’59. I lived on Klickitat between 29th and 30th at the time. In those days, as mentioned in John’s post above, you could hear and actually even see the mechanical switches operating in huge banks of switching gear. Pretty cool historical update. Thank you.

The loading dock was a popular spot for skateboarders in the late 80s and early 90s … we couldn’t believe that there was never anyone coming out to chase us away. Eventually a barrier was put up that put an end to skateboarding there …

I lived at 24th and Stanton across the street from the building. It always seem like a mystery building to us kids and we use to roll down it’s slopping lawn playing “King of the Mountain”. I remember when they built the additional parking lot on the north side and we always use to try to peak in the windows to no avail. Also toured the huge banks of switching gear which was pretty amazing as a child.

Pat, my sister, is right. The hill seemed much steeper than what it looks like in the picture. It was covered in grass and we paid little attention to the signs saying it was private property.

On warm nights in the 50’s and 60’s the employees would open the windows (the building was staffed all night and there was no AC). Our parents also opened their windows to keep cool, but the noise was a constant irritant. I guess it took a lot of angry phone calls, but eventually the building was air conditioned and the windows sealed shut (the phone co even gave my dad a tour of the building so he could see for himself that the windows had been sealed).

There’s a similar story of my dad objecting to the fact that all the parking spaces on both sides of Stanton were taken up by the employees. I think that may have been one reason why a parking lot was built.

I lived across the street from that building also. I don’t remember the hum, but I remember going into the building and seeing walls of wire. We played King of the Mountain there and on our lawn as well.

Ann, is your sister Susan Pendergrass, graduating from Alameda in about 1965?

Philip

2947 NE 24th Avenue was my family home from 1948 to 1967. My name is Genevieve Clare Adams Morrill. I am the second of my four siblings. John is the oldest, followed by me, my sister, Rose Mary Adams Price, and brother, Patrick who was only six months when we moved to our new home.

My parents were Walter Charles Adams and Genevieve Clare McCarty Adams, they purchased our home from the Templey Estate, owners

Templey Fur Company.

It had a huge front porch with a swing and tables for dinners outside on warm summer days (before air conditioning). A vestibule and formal front and dinning room. It also featured beamed ceilings and sliding wood pocket doors which our parents always closed on Christmas mornings so we could not see what Santa had left.

I remember a lovely kitchen with lots of windows, cupboards and a wood stove that produced yummy treats my Mom loved to bake!!

A big basement in which my siblings and I played school, and ping pong that also held the bikes we rode to school on cold days.

Up stairs were three bedrooms with walk in closets. My youngest brother had the sleeping porch.

The attic was a great place to look down on our neighbors.

We use to play hide and seek at night with the whole neighborhood. No one every worried who might be hiding in the shadows it was truly a different era.

We walked to school every day to the Madeleine. I was never allowed to eat lunch at school because I only lived a half a block away.

It was sad to leave my childhood home, but progress has no mercy.

One of our former neighbors told my Mother that as our house was falling down they heard a very LOUD almost human cry.

So sad this important family home is now lost to a parking lot. I would love to learn more about the house and neighborhood and share the story with Alameda History readers… Please contact me for further conversation.

Hi Genevieve. I have lived at 3042 NE 24th (corner of NE Siskiyou) since 1997. Do you have any photos of the outside of the house you grew up in located at 2947 NE 24th?

Very interesting article. I’m a preservation architect in Seattle undertaking a local landmark nomination of another one of the PT&T Exchange buildings. The one we are looking at is one of three similar buildings dating from the 1920s. Located at 440 West Garfield Street, on Seattle’s Queen Anne Hill, it was alos referred to as “the Garfield Exchange.” We’re still researching the original designers, an engineer with the company’s San Francisco Office (1921 original two-story building) and the company’s structural engineer, Arthur D. Codington, who apparently worked in its Seattle office (1929, 3rd floor addition). If anyone has more information about these exchange building, which appear very similar, please let me know. Thanks, Susan Boyle, sboyle@bolarch.com

I worked there when I was attending Grant High School. My neighbor was Ma Bell management employee and during a Christmas party his wife was offered a typing job. I was employed starting in approximately 1970 & continued through out high school & college. Plant department…so if anyone is interested would love to share. I grew up on 26th & Stanton…Alameda grade school…Patty