We had been focused on the work of John W. McFadden, a homebuilder operating in the Laurelhurst neighborhood of the 19-teens and 1920s, when we bumped into an interesting thread of newspaper stories related to the big traffic roundabout known today as Coe Circle, at the intersection of NE Cesar Chavez Boulevard and NE Glisan. The circle exists at the core of the 392-acre Laurelhurst subdivision, platted in 1909, which before the turn of the last century had been prime agricultural land known as Hazel Fern Farm.

You know this place, which features the gold-leaf statue of Joan of Arc given to the City of Portland in 1925 by Portland resident Dr. Henry Waldo Coe, Oregon State Senator, personal friend of Teddy Roosevelt and advocate for WW1 soldiers. Coe chose this statute because Joan of Arc, by way of a song (Joan of Arc, They Are Calling you), spurred the courage and devotion of soldiers singing and fighting in France in 1917-1918. But that’s another story. Plus, the statue didn’t come along until Memorial Day 1925, 16 years after the circle was first platted.

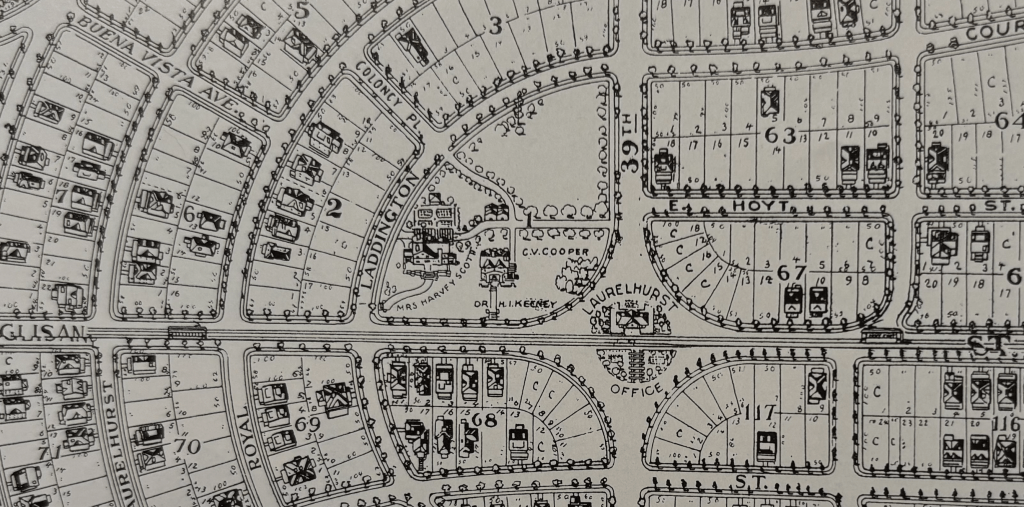

Coe Circle / “Block A” and the location of the Laurelhurst Company Tract Office, from “Laurelhurst & Its Park,” published in 1912.

The 80’ radius circle in the middle of the intersection had a few incarnations before it became the roundabout we know today, and in 1923 it narrowly avoided being turned into a retail hub, launching a dispute that shook the neighborhood. Add the traffic circle—today officially a city park—to the long list of places that nearly turned out very differently, including several of our favorite Northeast Portland parks which barely missed becoming subdivisions.

Up until the early 1920s, the Laurelhurst Company operated a real estate sales office on the north side of the circle, which was then divided north-south by the Montavilla Streetcar that traveled east-west on Glisan between Montavilla and downtown. A streetcar stop / real estate office was the perfect combination. During those years, most Portlanders traveled by streetcar, which was the ideal way to access the new eastside subdivisions to peruse vacant lots and dream about building a new house.

But by 1921, surrounding neighborhood lots had been bought up and it seemed to at least one builder/developer that what Laurelhurst needed more than a real estate office at that location was a place to buy groceries.

The Laurelhurst Company closed the real estate office in November 1921 and auctioned off the property, often referred to as “Block A,” to the highest bidder: builder/developer J.W. McFadden who knew the neighborhood well from building dozens of homes there.

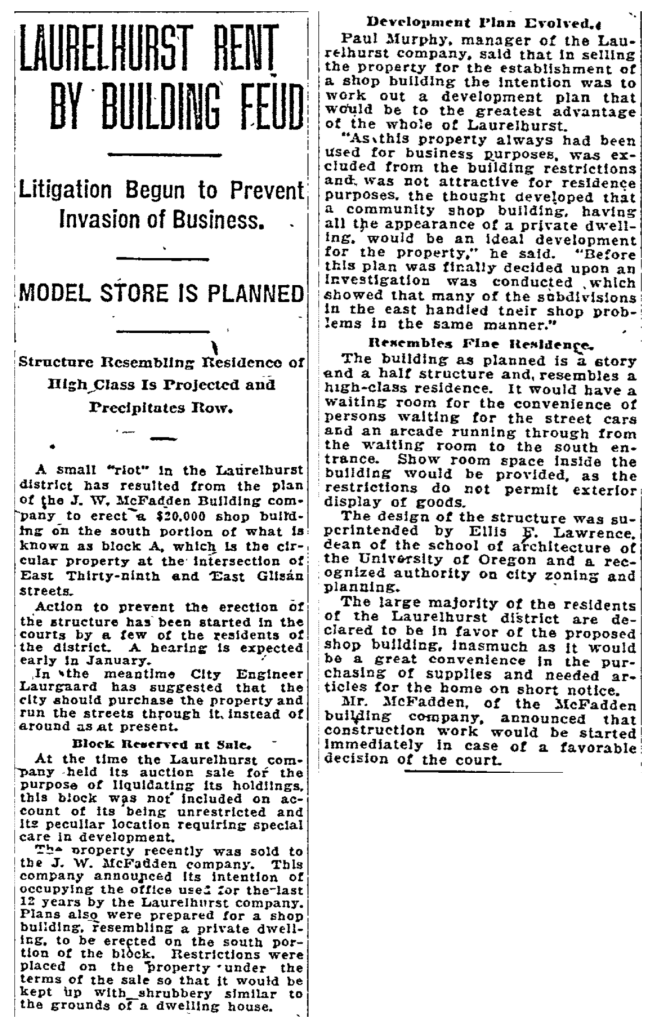

By Christmas 1921, McFadden’s plans to build a combined grocery, meat market and drug store on the south side of the circle with second-story apartments above, plus a filling station on the north side of the circle, ignited a battle in the neighborhood between those who liked the idea, and those who felt it compromised the residential feel of the place. McFadden hired talented local architect Ellis Lawrence, co-founder of the University of Oregon School of Architecture, to produce designs that would make the market a “handsome structure.”

Rendering of J.W. McFadden’s planned commercial hub to be located on the south side of today’s Coe Circle at NE Cesar Chavez and Glisan. From The Oregonian, December 25, 1921. The building was designed by Ellis Lawrence.

At issue was the interpretation of prohibitions on commercial buildings. Laurelhurst, like many eastside neighborhoods had racial deed restrictions and prohibitions against commercial buildings. But Block A seemed to be exempt.

From The Oregonian, December 25, 1921

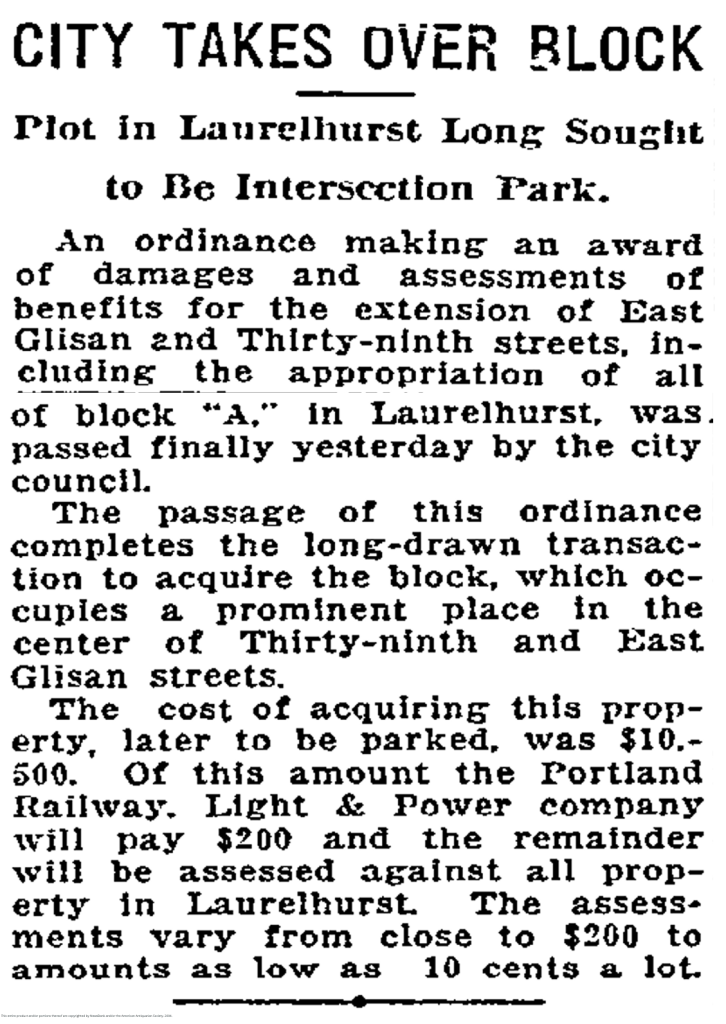

A “riot” might be a bit of an overstatement, but things did get heated, with adjacent homeowners who were attorneys filing an injunction against McFadden’s plans. Even Olaf Laurgaard, Portland’s City Engineer who lived in Laurelhurst on Royal Court, came out against the proposal and suggested a fix.

The case moved through Multnomah County Circuit Court in early 1922 and eventually the opponents lost: McFadden won the case that the commercial prohibitions did not apply to Block A. After all, the Laurelhurst Company had operated its commercial real estate office there for at least a dozen years.

From The Oregonian, March 5, 1922

The day after the circuit court decision, attorney-homeowners petitioned Portland City Council to seek other means by eliminating the circle altogether and turning it into a city street thus scuttling McFadden’s development plans. City Engineer Laurgaard’s fingerprints begin to show in this approach. Must have been a fine line to walk both as concerned neighbor and city official in charge of street engineering.

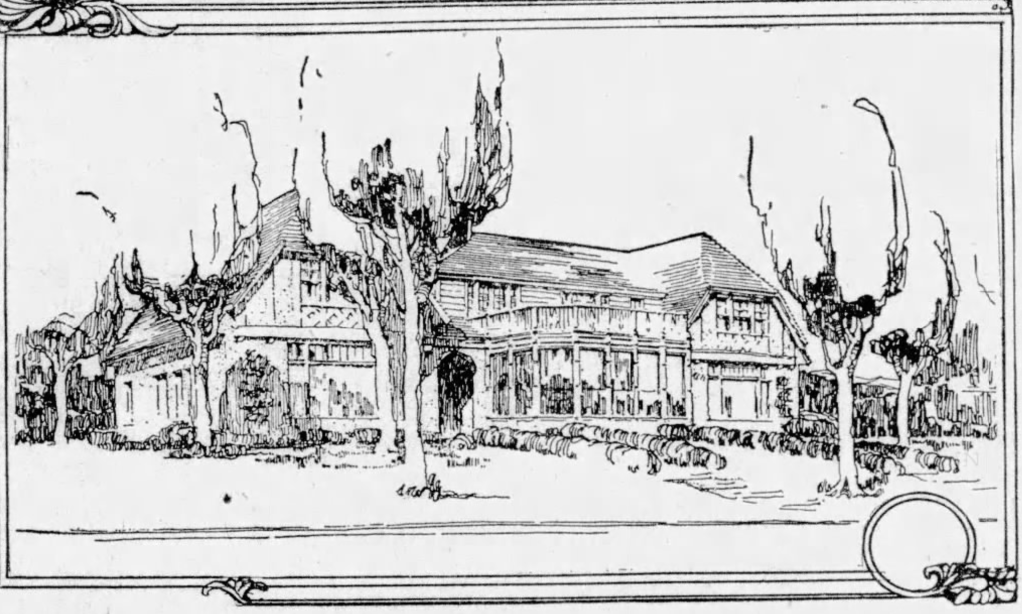

The case percolated through city politics that spring and summer, but by August 1922, Laurgaard and development opponents had figured out a course of action that involved the city buying out McFadden’s interest using mostly one-time special assessment funds paid by Laurelhurst residents and a token amount paid by the streetcar company. In August, City Council passed an ordinance codifying the “compromise.” McFadden dropped his plans, Laurelhurst neighbors paid their one-time special assessment to buy Block A, and the city added its latest city park.

From The Oregonian, August 24, 1922.

The Joan of Arc statue came along in 1925. Next time you pass by, note that it’s not in the middle of the circle, but slightly to the south because at the time, the streetcar still passed directly through the middle as it traveled along Glisan Street. As you make the round, tip your hat to City Engineer Laurgaard and the neighbors who pushed for the park, and the early generation of Laurelhurst residents who paid their special assessment to make it happen.

For the record, builder John Wesley McFadden went on to become one of Portland’s more prolific and respected residential builders in Laurelhurst, Alameda and other northeast neighborhoods. During Portland’s building boom period of the 1920s, in addition to high-profile homes, apartment buildings and movie theaters, the J.W. McFadden Company built dozens of middle market and entry level bungalows on Portland’s eastside, mostly using designs and blueprints produced by the Universal Plans Service.

In 1931, McFadden built “Bobbie’s Castle,” a scaled-down bungalow memorial to the famous Silverton-area collie dog that walked 2,800 miles from Indiana back to its owners in Oregon. Bobbie was buried at the Oregon Humane Society in Northeast Portland, and McFadden’s memorial to him—a small house—was located at the dog’s grave there.

In 1937—at age 56—McFadden joined with financial backers to create Modern Builders, Inc. to build multiple apartment buildings in southeast and southwest Portland. He died in Portland at age 68 on February 3, 1950.