For more than 40 years, a dignified and simple clapboard-sided wood frame church presided over the corner of NE 33rd Avenue and Webster, serving as a local landmark for its parishioners and for the neighborhood that was steadily growing up around it.

Old St. Charles Church, March 1931. Looking southeast at the corner of NE 33rd and Webster. Note that 33rd (at right) is paved, Webster (to the left) is not paved. Photo courtesy of the Archdiocese of Portland in Oregon Archives.

The original St. Charles Catholic Church has been gone now for almost 70 years and recollections about its life and times are slipping close to the edge of living memory. The parish relocated to its current home on NE 42nd in 1950 and demolished the original building. But when you know where it once stood and its place in the evolution of the Concordia, Vernon, Cully and Beaumont-Wilshire area, you’ll want to keep it alive in your own imagination and sense of place.

Let’s put the ghost of this old building on the map: Webster is the east-west street intersecting NE 33rd Avenue just north of Alberta and just south of today’s New Seasons Concordia grocery store. The church was sited with its long side adjacent to Webster, and front doors and stairs facing 33rd, right at the corner.

Detail of 1940 aerial photo showing location of original St. Charles Church at the southeast corner of NE 33rd Avenue and Webster Street. Photo courtesy of University of Oregon Map and Aerial Photography Library.

In February 2019, construction is underway on the site: a three-story 12-plex apartment building, which is being built pretty much in the footprint of where the church stood from 1916 until its demolition in 1950. In fact, while excavating recently for new footings, workers came across parts of the foundation and basement slab of the old church.

Looking southeast at the corner of NE 33rd and Webster, February 2019 (above). The same view in much earlier years (below), photo courtesy of St. Charles Parish Archive Committee.

Below is the Sanborn Fire Insurance Map plate from 1924 that will give you a good snapshot of where the building stood (upper left hand corner), and just how sparsely built up the surrounding area was then (click to enlarge the view). Read more and see other old photos in this recent post about the intersection of 33rd and Killingsworth, this post about Ainsworth and 33rd, and this post about the old fire station one block south at Alberta Court and 33rd.

Knowing what you know now about the prominent role local property owner John D. Kennedy played in shaping the area from 1900-1930 (his early influence can’t be overstated), you won’t be surprised to learn the church building and the entire St. Charles Catholic Parish trace its founding back to him. Parish historians Jeanne Allen and Joseph Schiwek Jr. both credit Kennedy with encouraging then Archbishop Alexander Christie to found St. Charles Parish in the first place, sometime in late 1913. Kennedy did all he could (including providing property for a public school) to create a community from the surrounding rural landscape.

In March 1915, the Catholic Sentinel newspaper characterized the area and its scattered population like this:

“This parish, which is in sparsely settled territory in the northeast portion of the city is made up of earnest workers.”

Said a little less carefully, everyone knew this area was out in the middle of nowhere in comparison to the rest of Portland proper, and that most of the people who lived here were immigrants and first-generation citizens from Italy, Ireland and Germany.

The newly founded St. Charles Parish congregation of 25 families held its first mass on February 3, 1914, in a grocery store built and owned by Henry Hall near the corner of NE Alberta and 32nd Place. Here’s a look at that old store, which stands today. It’s one of the older buildings on Alberta Street, by the way, dating to 1911. The congregation held mass there every Sunday from February 1914 until the completed church was dedicated and opened on October 1, 1916.

3266 NE Alberta (formerly 986 East Alberta before Portland’s addressing system was changed in 1931), originally known as the Hall building and later as Herliska Grocery. Photographed in February 2019. High mass was said here every Sunday between 1914-1916. The building is one of the oldest in this section of NE Alberta.

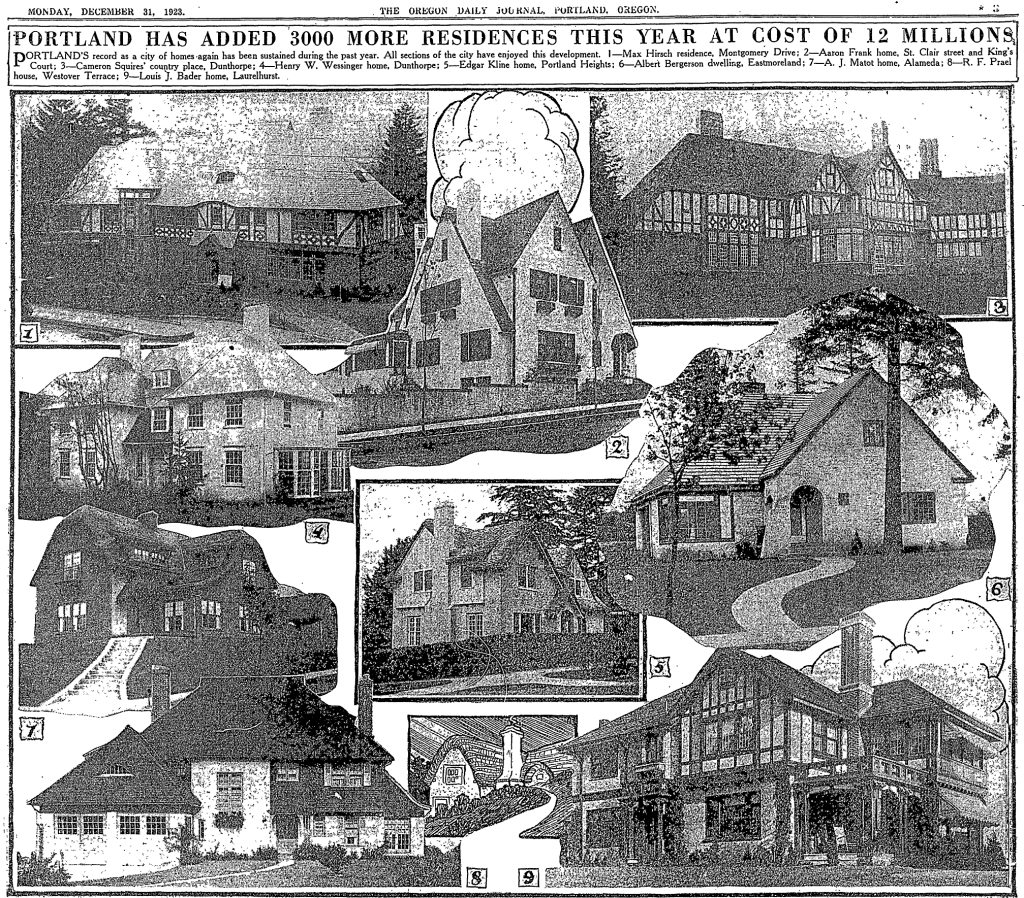

News stories during that interim reported on the new building’s planning and construction, sharing details from Portland architects Houghtaling and Dougan about the 40’ x 80’ wood frame building with its full concrete basement hall (think potluck dinners and parish events), including this rendering (we particularly like the clouds):

From The Oregonian, June 4, 1916

The church steeple, rising some 50 feet above the street, didn’t turn out quite like the rendering: an octagonal tower with cross was built instead of the traditional peaked steeple. Here’s another view, from sometime in the 1940s.

Photo courtesy of St. Charles Parish Archive Committee

The dedication was covered by The Oregonian, the Oregon Journal and the Catholic Sentinel. All three newspapers noted the church building was just the first phase of construction that would eventually include a parish school and a rectory.

By 1918, with help from John D. Kennedy, the parish bought the two lots immediately to the south with the future in mind: one was vacant and the other held a house that became the rectory. A growing number of young people in the St. Charles parish—many of whom traveled to St. Andrews at NE 9th and Alberta and some to The Madeleine at 24th and Klickitat—had hopes of a school closer to home and the congregation was doing everything it could to save and raise money.

These photos show the rectory (inset) and its location two lots south of the church. You can see the northwest corner of the rectory at far right in the larger photo. From The Catholic Sentinel, March 4, 1939. The rectory was moved to the new site on NE 42nd in 1950, and destroyed by fire in 1978.

These photos show the rectory (inset) and its location two lots south of the church. You can see the northwest corner of the rectory at far right in the larger photo. From The Catholic Sentinel, March 4, 1939. The rectory was moved to the new site on NE 42nd in 1950, and destroyed by fire in 1978.

But in 1924, the parish experienced a major setback when an overnight fire on June 27th did significant damage to the church building, altar, pews, statues and paintings that added up to almost $3,500: a major loss that would not soon be overcome.

The origin of the fire was disputed at first (fire investigators not really wanting to talk about arson) but then emerged in the stranger-than-fiction tale of Portland firefighter Chester Buchtel. A capable firefighter from an established Portland pioneer family, Buchtel admitted to setting at least 16 fires in 1923-1924–destroying Temple Beth Israel and the German Lutheran Church, both downtown, the St. Charles Church, lumber mills, garages and barns city wide–and causing more than $1 million in damage.

Repairs were made and the building was rededicated on November 23, 1924, but the wind was out of the sails for any school development fund, which continued to be the case through the Great Depression years and beyond.

Parish historian Schiwek picks up the story in the mid 1940s at the end of World War 2, from his book, Building a House Where Love Can Dwell: Celebrating the first 100 years of the St. Charles Borromeo Parish, 1914-2014:

“There were now thousands of GIs coming home to start life afresh with new homes and new families. Such was the case in Northeast Portland. Many new houses were built as families moved into the parish, with the result that by 1950, the old church, that was only capable of seating 300 persons, was fast becoming obsolete. Moreover, demand for a school was increasing and there was no land available at the existing site to build one. There were over 300 Catholic children in the parish at this time and at least half of them were attending neighboring parish schools that were themselves overcrowded and the rest were in public schools without any religious education.”

In the spring of 1950, Archbishop Edward Howard made a change in parish leadership. By that summer, the parish had obtained a site and was into construction on the St. Charles school and campus that exists today 12 blocks east at NE 42nd and Emerson. The old rectory was jacked up from the lot south of the old church and trucked to the new site in a careful two-day moving process.

The final mass at the old church was held on October 15, 1950. A photograph was taken from the church balcony to document the end of an era. And on October 22, the new St. Charles was dedicated with mass held in temporary quarters on the new site until the new church building could be completed in 1954.

Photo courtesy of St. Charles Parish Archive Committee

Long-time parishioner Jeanne Allen remembers that while there was excitement about the move to a new site and anticipation about the brand-new school and fresh start as a community, leaving the old building was hard on some of the established families who had known it all their lives. So many family events—baptisms, weddings, funerals and every Sunday in between—took place there at the corner of NE 33rd and Webster.

“There was something very comforting about the inside of the old church,” she recalled recently. “It was simple, dignified, spiritual.”

With the parish installed in its new quarters, the old church was demolished, likely sometime in 1950. No parish records remain about the demolition and property sale, nothing in the newspapers and no one we’ve spoken to remembers those final actions.

Photo courtesy of St. Charles Parish Archive Committee