Last month we began a series of stories about the prominent yellow stucco home in the Alameda neighborhood at the confluence of NE 24th, Mason and Dunckley streets. In our first installment, we met the house and its most recent residents–the von Homeyer brothers–at the close of almost a century of that family’s occupancy.

The home was built by their newlywed parents Hans and Frances in 1925-1926 and occupied until recently by the youngest son Karl, now in his 90s. Older brother Hans (referred to as “Hansey” to distinguish him from the father Hans and the grandfather Hans) lived in the house all his life too, and died in 2002.

Because both generations of the family saved so many things–particularly paper–we can gain a special insight into the homebuilding process of the 1920s that has been lost to time for most other homes of this vintage.

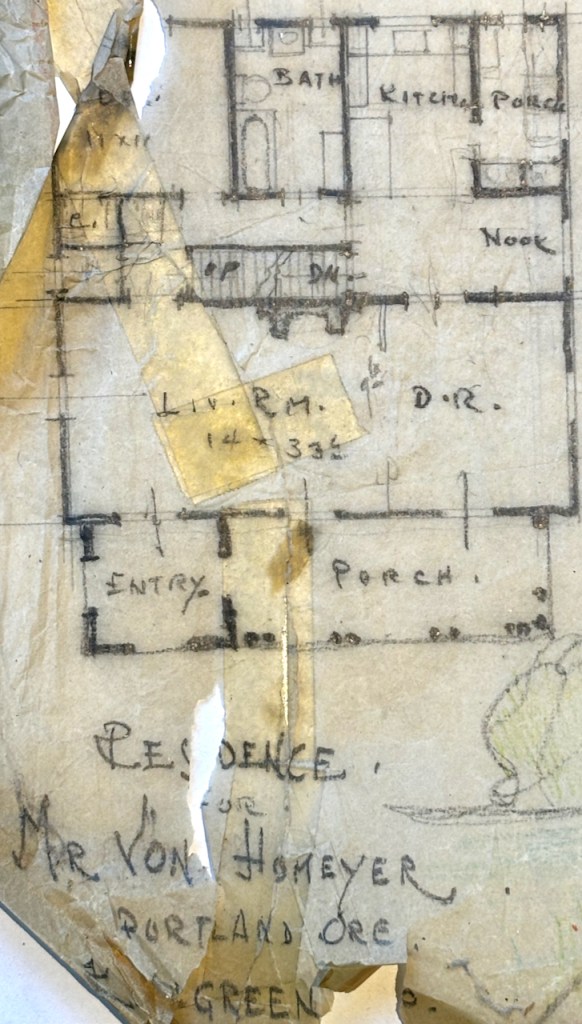

For instance, an early sketch of the house by architect Ragnar Lambert Arnesen, on onion skin paper, along with a floorplan.

Arnesen, then a 29-year-old immigrant from Stockholm, worked with Killgreen and Company, a design-build commercial and residential construction firm that started up in 1925 at the peak of Portland’s homebuilding business (by the way, the Swedish influence on Portland homebuilding is significant). By 1930, Arnesen had relocated to Dearborn, Michigan, and Killgreen and Co. had been shuttered by a collapsing economy.

Hans von Homeyer was 27 years old in 1925 and busy establishing himself. He might have come across Arnesen and Killgreen from an advertisement in The Oregonian, like this one from April 19, 1925:

Hans was in business with his brother and his parents who owned multiple cleaning and dyeing shops in Portland and Vancouver, so his own network was wide…maybe that’s how he came across Killgreen. We’ll share more about the von Homeyer family business in future posts because it’s a very interesting story and the photos are fascinating as well.

Hans and Frances Westhoff, daughter of a Vancouver clothier family, were engaged to be married and looking to start their family and home in Northeast Portland. They found the lot in the Alameda neighborhood (which was then only about half built-up), engaged Killgreen and its architect Arnesen, took out a mortgage, and got down to the business of planning and construction.

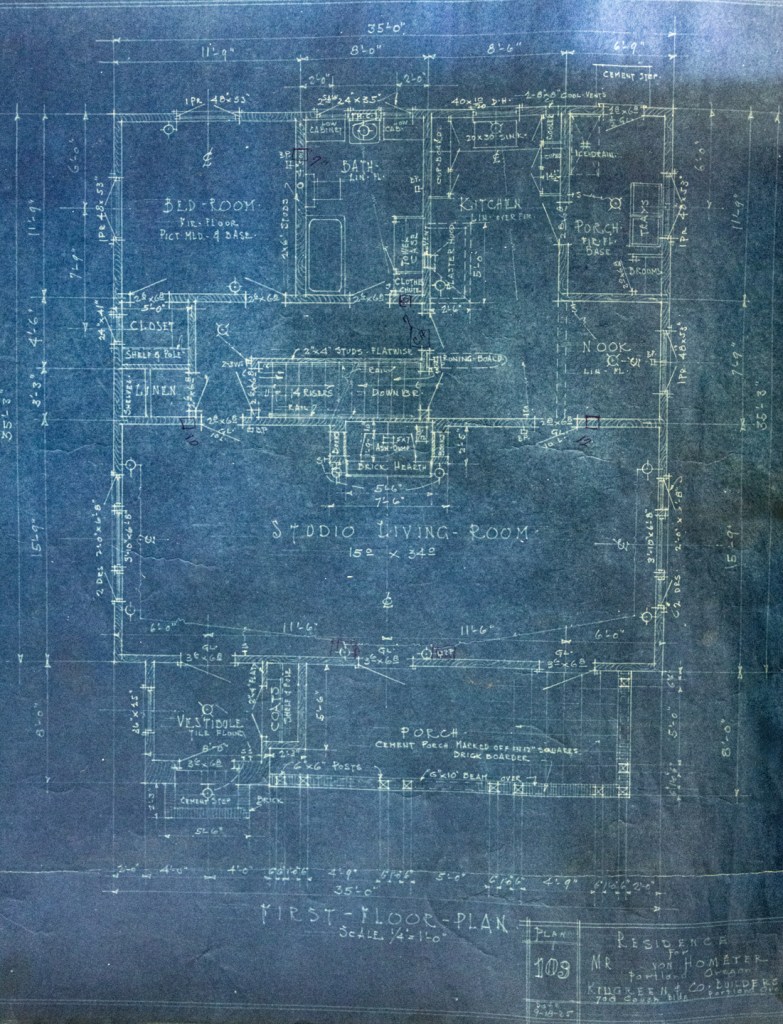

Arnesen’s early sketch led to the set of blueprints:

An important note: in the time between the first sketch and the blueprints, the primary shared living space in the home went from “Liv. Rm D.R.” to “Studio Living Room,” a hint of a much larger story.

Frances, then just 24, was an accomplished pianist building her own network as a well-known and respected piano teacher. She needed a studio to house her piano, two organs and teaching space. Ultimately, the house was designed to accommodate piano teaching and performance, which flourished in the years that followed. We’ll write more about Frances and her piano in future posts. Her gift for music touched hundreds of students–everyone in Alameda and surrounding neighborhoods knew her and plenty learned and played in that big room. Her music defined that space for so many years.

Back to the ad hoc archive of what the von Homeyers saved that allows us a view into the homebuilding process:

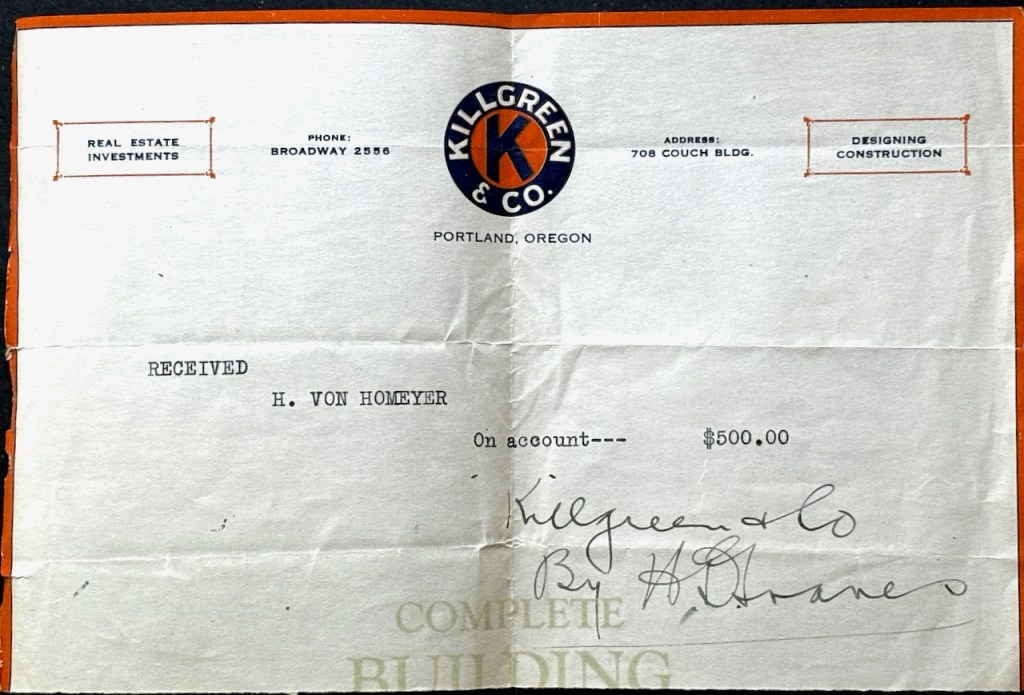

The contract–a signed agreement between Hans and Killgreen dated October 2, 1925 for the total cost of design and construction: $3,780, paid on completion of the house, with $500 at signing of the contract, $540 each week for five weeks and $500 upon completion of construction.

A copy of the receipts from Killgreen for each payment:

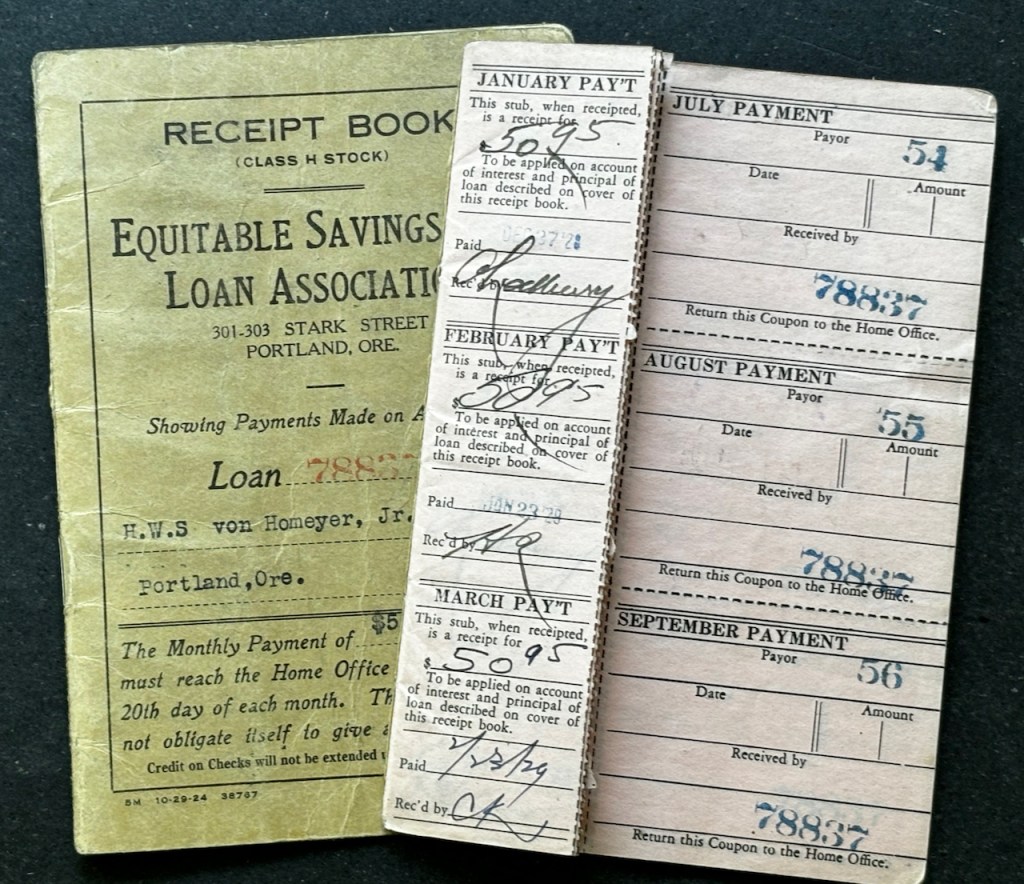

The bank receipt book from Equitable Savings and Loan with the monthly mortgage payment stubs for $50.95, paid through May of 1930:

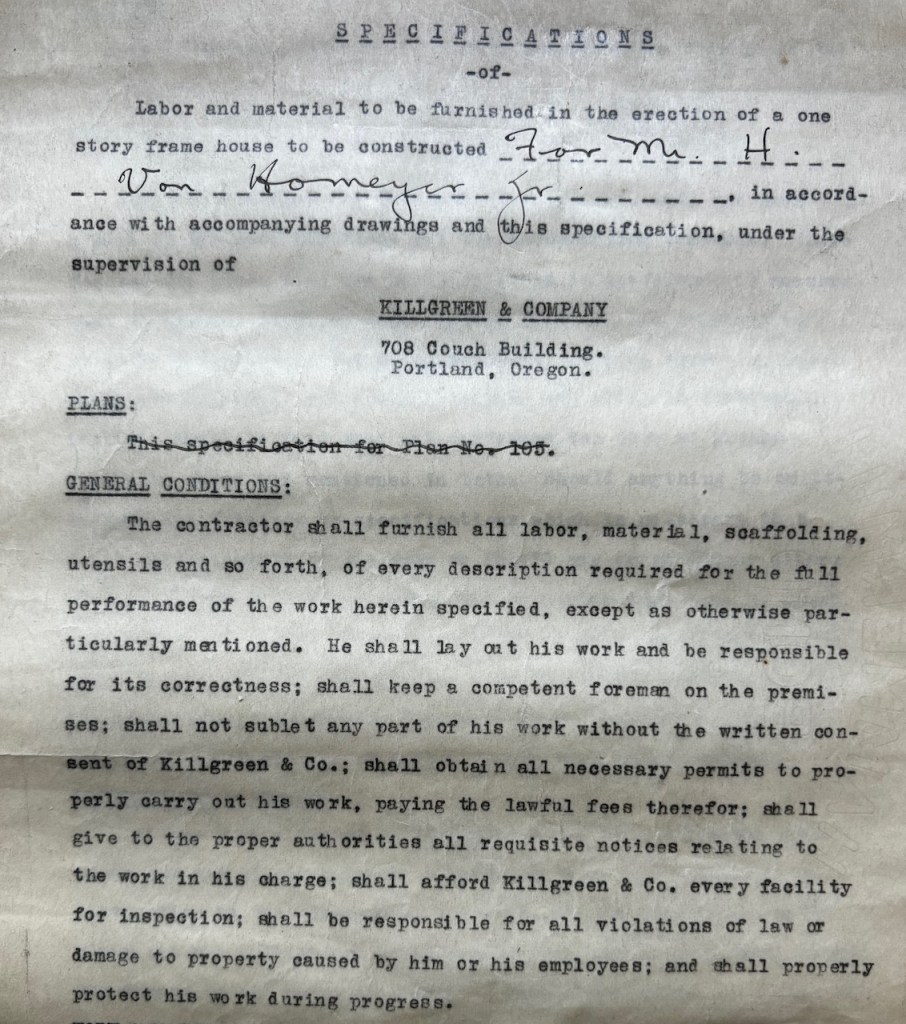

Thirteen pages of written specifications for construction of the house that accompanied the blueprints and pertained to every detail including the amounts and types of sand, mortar and lime that would be used for brickwork:

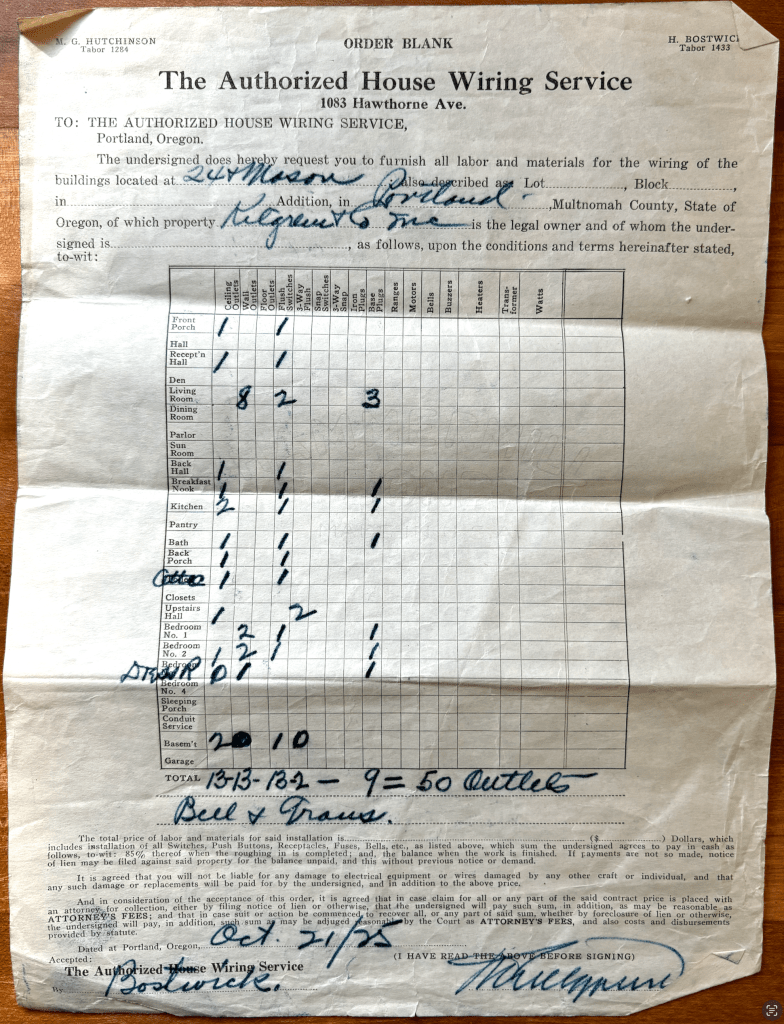

A detailed listing of all house wiring components installed by electricians (one of our favorites):

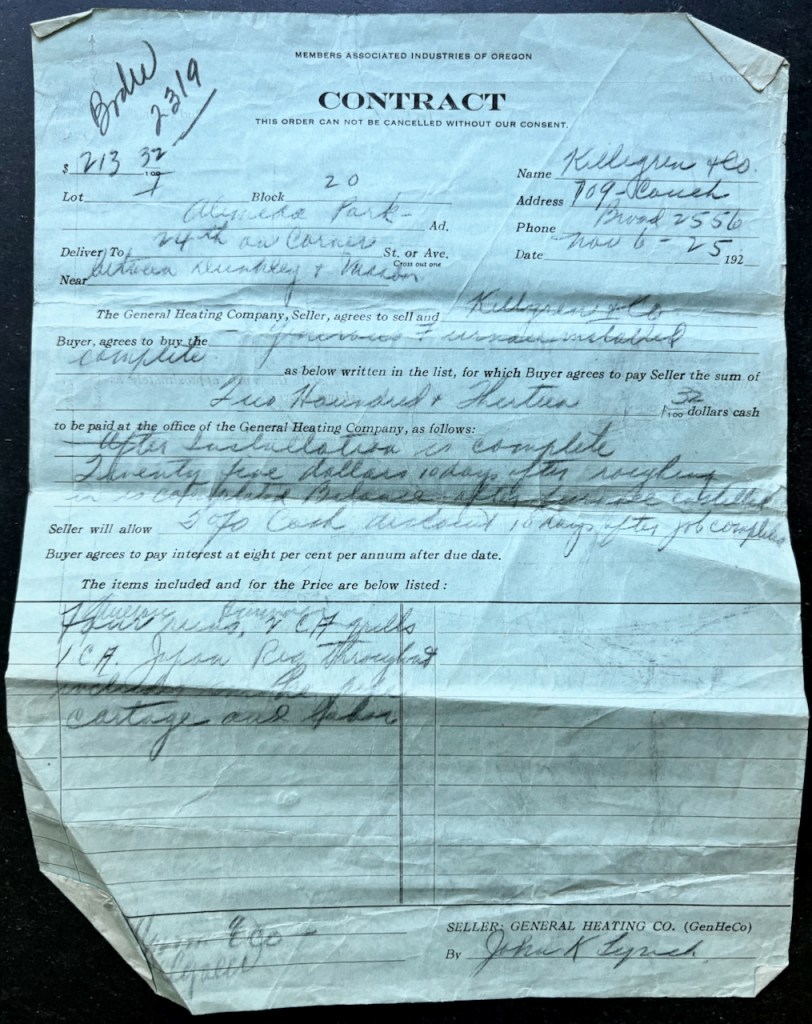

The contract with General Heating Company for installation of the furnace: $213.32:

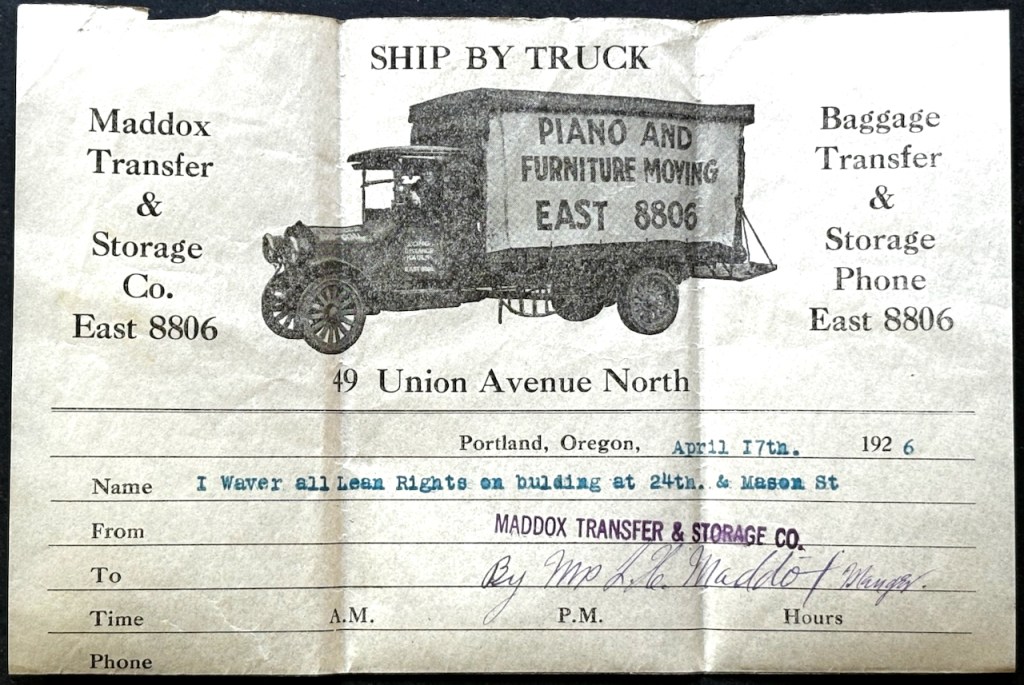

And perhaps the most important document, a receipt from piano mover Maddox Transfer dated April 17, 1926, which is a good indication of when the couple–and Frances’s piano–moved into the house:

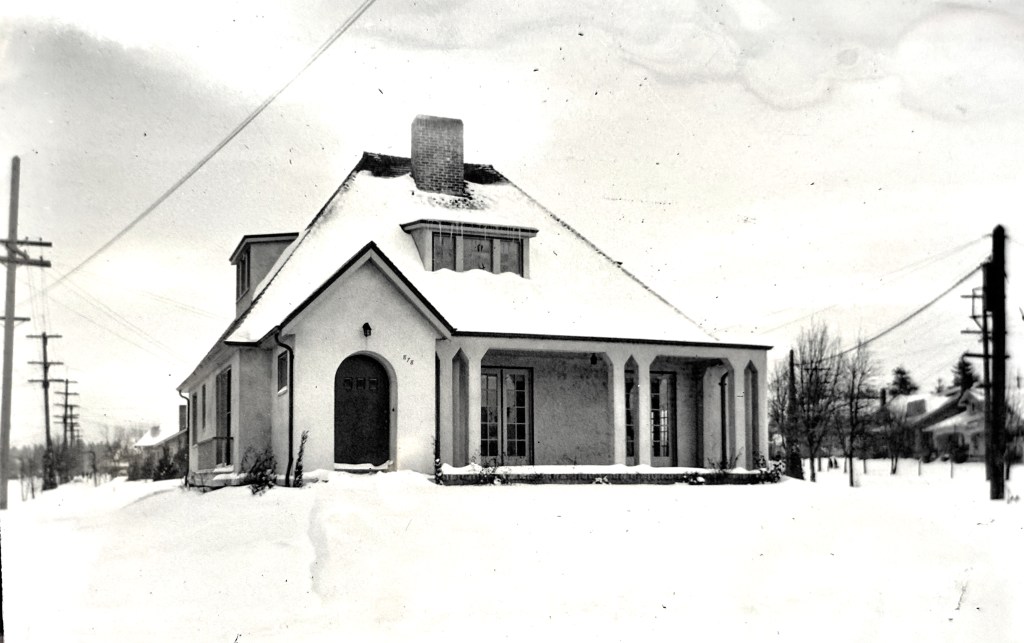

In addition to the many receipts, contracts, correspondence and other documents related to construction, several photographs from the winter and spring of 1926 document the process.

Construction clutter indicates work still underway

Almost done. The small building in the parking strip is a saw shed, which housed the builder’s tools and supplies. Saw sheds were common on residential construction sites.

The finished home, addressed as 878 East 24th Street North, before Portland’s Great Renumbering.

How unusual it is to be able to see all these moving parts associated with the homebuilding process from the 1920s. Not so different from business agreements, loans, waivers and releases today. But more personal, more detailed, more bespoke than the computer printouts of today.

That the family kept them together in a set of files all these years–along with the abstract of title, the deed and other documents–signifies their importance, a kind of family trove of sacred documents. Now, they’re all organized and safe and will be staying with the house going forward.