We’ve been reflecting on the legacy of the rivers and the people who for millennia defined the landscape we think of today as Portland. It is both inspiring and beyond tragic when we consider what was, and what has been lost.

This week, we want to help imagine that early landscape.

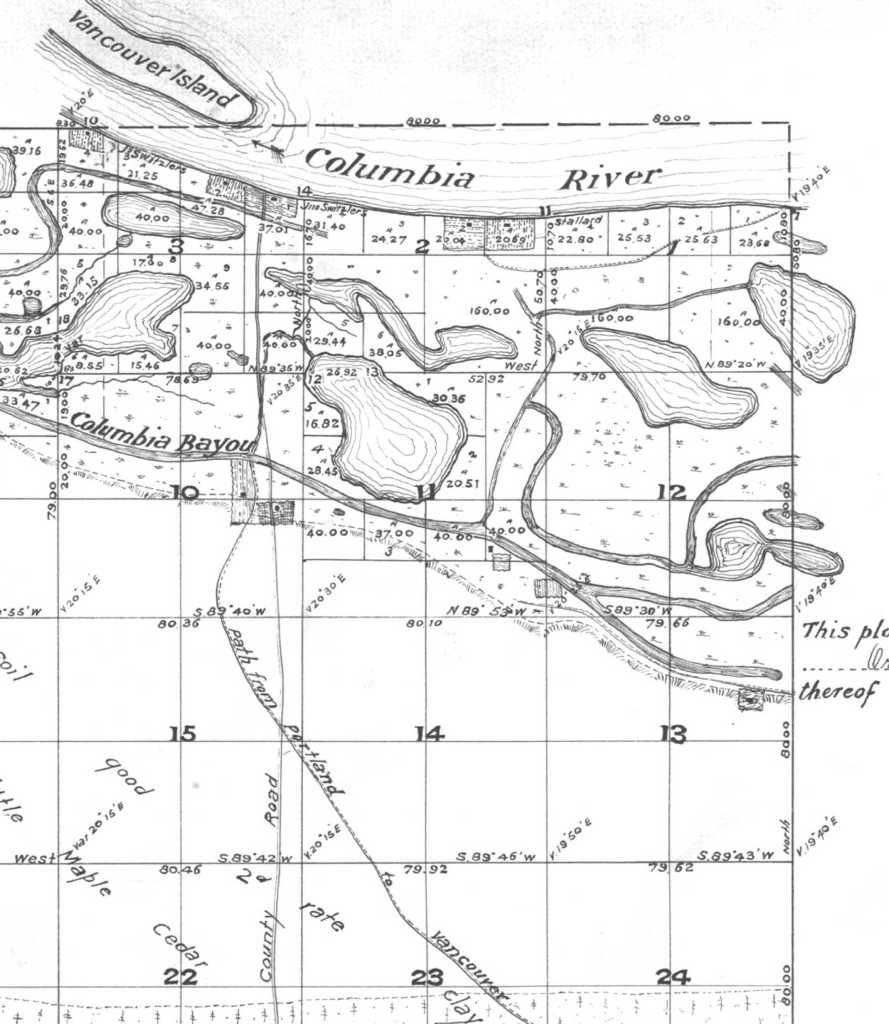

Here’s a detail from an 1852 map that conveys the complexity of the margin between river and shore in the northern edges of today’s Northeast Portland. Have a good look and we’ll discuss.

Detail of 1852 Map of Township 1 North, Range 1 East, Courtesy of Bureau of Land Management Cadastral Survey Records. The complete map plate is here in our Maps collection.

The island labeled “Vancouver Island” is today’s Hayden Island. For orientation purposes the number 24 (which is Section 24 in Township 1 North, Range 1 East) is at the intersection of NE 33rd and Prescott Street. The far right edge of this map running up and down follows the line of today’s NE 42nd Avenue.

For those of you familiar with the Willamette Meridian, NE 42nd Avenue scribes the section line between Range 1 East and Range 2 East. The number 13 is just west of today’s Fernhill Park at NE 33rd and Holman. Today’s Columbia Boulevard runs northwest-southeast just at the base of the slope (the slope is scribed on this map as a hatched line just south of the waterway).

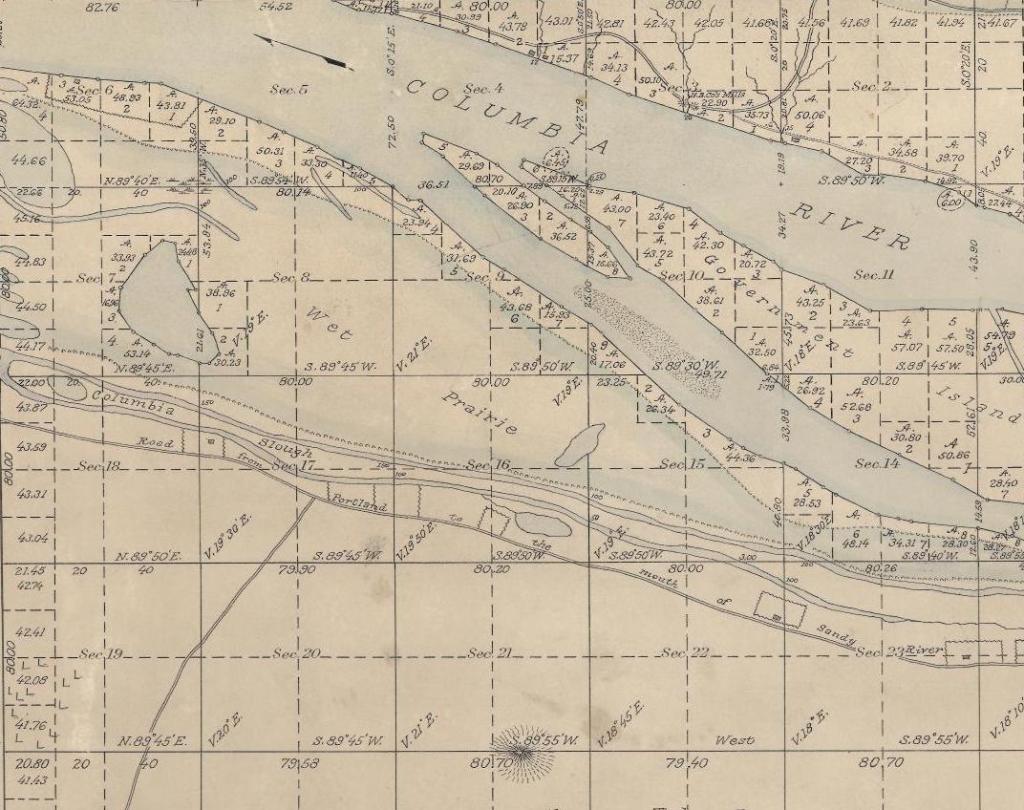

Here’s another early map that continues the look east on the Columbia shore.

This 1850s map, of Township 1 North, Range 2 East, shows the location of today’s Portland International Airport in the area between the two lakes labeled as “wet prairie,” telling us the area was typically inundated during high water. A large shoal or shallow area exists in the Columbia between shore and Government Island. The road angling up from the bottom is today’s NE Cully Avenue (the Cully family was here in 1846). The topography showing in the bottom center is Rocky Butte. This early map shows today’s Columbia Boulevard, labeled “road from Portland to the mouth of Sandy River.”

Detail of 1852 Map of Township 1 North, Range 2 East, Courtesy of Bureau of Land Management Cadastral Survey Records. The complete map plate is here.

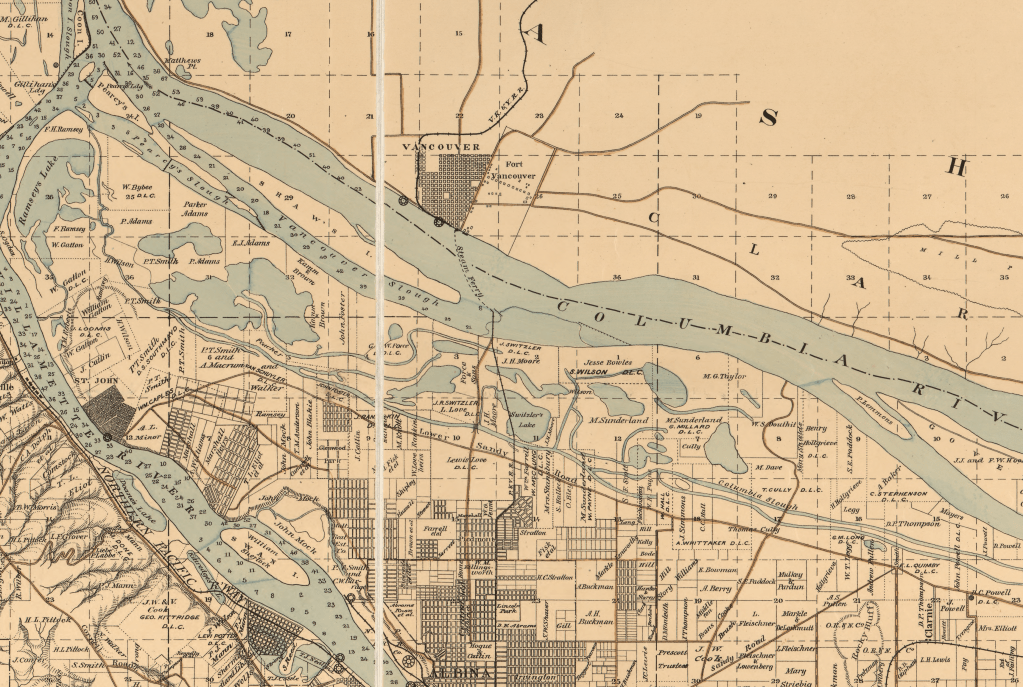

Here’s a detail from one more map that conveys the complexity of our northern edge: an 1889 land ownership map of Multnomah County compiled by R.A. Habersham, on file at the Library of Congress. In the 40 years between these two maps, the degree of landscape change is almost hard to imagine, with a grid of streets, residents and industry beginning to utilize these northern waterways as a vast sewer system.

Detail of Map of Multnomah County, Oregon 1889, courtesy of Library of Congress. Here’s a link to the full map (it’s a big file).

We’ve thought a lot about what this area must have looked like, and the people who lived here since time immemorial. We’ve wanted to find an approximation to suggest what all that changeable marshland might have felt like, and you don’t have to look far. Recently, we took the kayak to the Ridgefield National Wildlife Refuge just downstream from our reach of the Columbia and offer these photos to feed your imagination:

Imagining a “wet prairie.” That’s the reconstructed Cathlapotle plankhouse on the left at Ridgefield National Wildlife Refuge. February 2021

Thanks for your continued extraordinary attention to details such as these, Doug. Profound changes to the landscape and paying respect to the original inhabitants of this land. (And reminding your readers as to what this extraordinary landscape looked like, pre-settlement.)

Thanks, Doug, for a lot of research and leg work. It is interesting to me especially as this was our playground as a kid while living in NE Portland. We used to bike to the river and play in some of the out of the way spots. The change is very substantial even since the 1940s. Thanks, del Schulzke.

Thank you for sharing your curiosity.

You’re right on target, Doug. The dike, on which Marine Drive is now situated, was built 1919. Before that and before the Bonneville Dam was built, the Columbia River flooded with the spring freshets. Dwellings on the river were occupied seasonally, as evidenced by the Lewis and Clark journals. The area north of the southern arm of the slough was seasonally wet.

Thomas Cully arrived in Oregon in late 1845 without any family. He made 4 provisional claims before settling in what is now called the Cully Neighborhood in 1847. He married in 1850 and started his own family withi his first child in 1852.

Susan

You may have come across this as part of your research, but a January 2020 Army Corps of Engineers report, “Portland Metro Levee System Feasibility Study,” has an accompanying appendix, “Integrated Feasibility Report and Environmental Assessment: Appendix H: Cultural Resources,” which provides a trove of additional maps and research on pre-contact history and culture in the Columbia Slough. You can download it (PDF) via the following link: https://usace.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/api/collection/p16021coll7/id/13116/download

Indeed, came across this along the way, full of additional detail, recommended reading.