Plats are the puzzle pieces of our urban geography: invisible grids tied to a much larger grid known as the Willamette Meridian; part engineering plan, part map, part marketing pitch. Developers were required to submit them to the Multnomah County Surveyor’s Office before they divvied up the landscape. Today more than 900 individual plats make up the City of Portland. Knowing this provides a passport into the city’s development history.

But sometimes, the ones that don’t get developed are as interesting as those that do.

A recent research assignment took us up Cornelius Pass Road into the northwest reaches of Portland’s west hills, high above Sauvie Island in pursuit of the story of Folkenberg School, a 1913 Craftsman-style one-room building that operated for 23 years until the Great Depression and school consolidation forced its closure.

Folkenberg School in May 2024, courtesy Alan Baylis, RE/MAX Advantage Group, and REPIXS.

Leaning on our research, Portland Monthly just wrote a nice piece about the old school, which was converted to a residence in the early 1970s and recently placed on the market.

The simple school—built without indoor plumbing, heated by woodstove and lighted by tall windows that flanked the single large room—existed at the center of the Folkenberg Addition, a 51-block planned community that its developers dreamed would one day be an extension of Portland.

Portland experienced a land rush in the years after the 1905 Lewis and Clark Exposition, which attracted 1.5 million visitors, many of whom liked what they saw and wanted to stay. Much of Portland’s eastside was developed during this time, with new neighborhoods being platted every month, carved out of agricultural and forest lands. Real estate speculators made fortunes as lots were measured out, entire neighborhoods established and homes built.

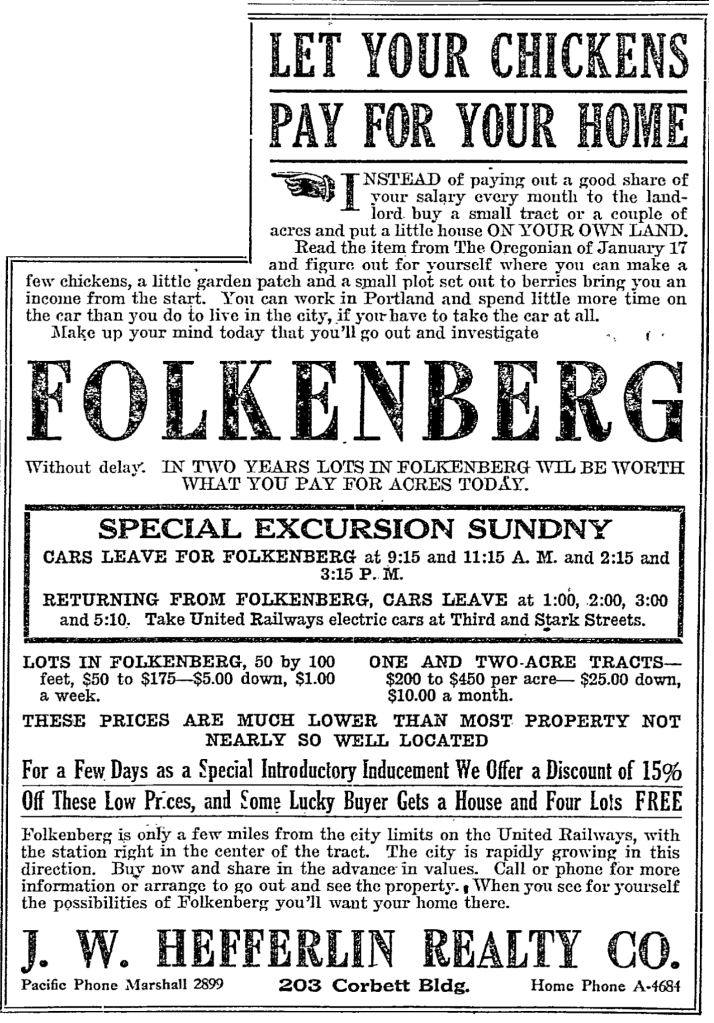

That same housing boom fueled interest in other undeveloped lands within striking distance of downtown. When he filed his plat for the Folkenberg Addition in January 1911, realtor and land speculator R.W. Hefferlin was probably thinking about the newly built Heights neighborhoods of Portland’s westside—Willamette Heights, King’s Heights, Arlington Heights, and Hillside. Still, he recognized the reality of the surrounding rural landscape and in fact promoted the revenue generating aspects of chickens, fruit trees and nearby fields.

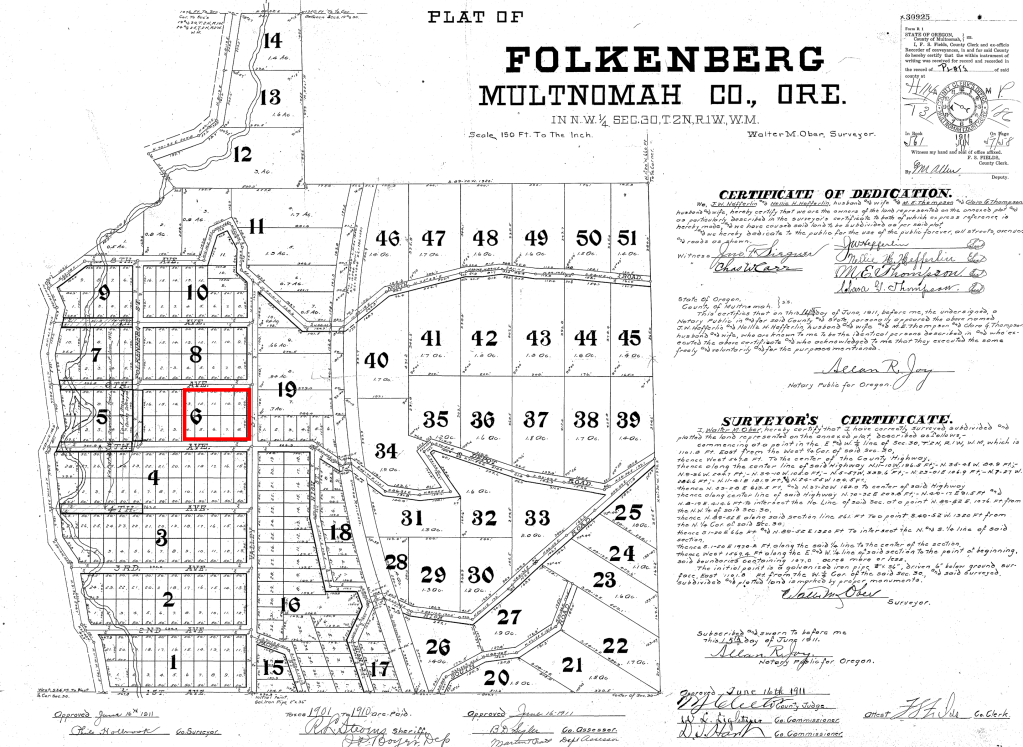

Folkenberg Plat, 1911. Click to enlarge. Red box indicates location of Folkenberg School. Cornelius Pass Road is at far left. The wide arc sweeping through north-south is the United Railways line. Nearby were other plats with similar ambitious planned developments.

In February 1911, United Railways completed a 4,103-foot railroad tunnel through the hillside, making a graceful arc right through the heart of Folkenberg and connecting the Tualatin Valley with Portland. Hefferlin made sure there was a rail passenger platform built in Folkenberg, and even named one of the improbable roads Depot Street to make sure everyone knew about the rail link. Remember, in the time before widespread use of automobiles, connecting subdivisions to Portland by rail was the number one factor ensuring property sales.

The namesake Folkenbergs were a Norwegian immigrant family who worked 300 acres in this area and ran a small sawmill. Patriarch Louis Folkenberg died unexpectedly in 1892 at age 54 leaving wife Inger Maria and 10 children, ranging in age from three to 24. By 1911, with children fledging and needs changing, the family sold off 107 acres for $14,455 to developer Hefferlin, who divided it up and began selling lots.

From The Oregonian, January 25, 1911. The home Hefferlin advertised as giving away free was the 1880s farmhouse built by Louis and Inger Maria Folkenberg.

When he platted Folkenberg, Hefferlin was already in the process of platting and marketing other nearby subdivisions known as Bayne Suburban Farms and Thompson Gardens, which were joined by other adjacent planned subdivisions called Sheltered Nook, Ingleview, Greenoe Heights, Cornelius Park, and Plain View Acres.

In 1913, the arrival of a few new families, and hopes for many more—plus the presence of many young Folkenbergs—eventually led to the call for a school to serve the area. Previously, children from this area traveled down the hill by foot or horse and wagon to Holbrook, Burlington or Linnton for schooling.

At its peak in 1916, the school had 33 students. But by the early 1920s, it was becoming clear J.W. Hefferlin’s suburban vision for Folkenberg was not going to pan out. Property sales slowed and then stopped. United Rail Lines focused on freight, not passengers. The area, as it turned out, was not within easy striking distance of downtown and in fact the people who wanted to live here were not particularly interested in things related to city life.

In the late 19-teens, Hefferlin stopped paying property taxes on the remaining lots he was trying to sell. Then in the summer of 1923, he gave up all together and moved to Los Angeles.

Through the late 1920s and into the Great Depression of the early 1930s, school enrollment slumped. In 1936, with enrollment down to just six students, parents in the area voted to close the school, sending the remaining kids to Holbrook School down the hill on Highway 30.

Folkenberg and its neighbor plats, conceived at a time of optimistic growth, remained the mostly rural lands they are today. The plats became ghosts, just lines on a map. The tax lots are still there, rolled together now into larger holdings. But Hefferlin’s idea of the next-big-thing westside neighborhood fled with him to Los Angeles, leaving behind a deserted old school tucked into a hilly rural landscape that faced years of hard use and deferred maintenance until new owners came along in the early 2000s to bring it back to life.

Want more on plats? We have an entire category!

very interesting.. I believe Louis Folkenberg was my relative.

Todd Louis Folkenberg