The intersection of NE 42nd and Killingsworth can feel like it exists on the way to somewhere else. But this crossroads has its own rich history that runs deep.

NE 42nd and Killingsworth, looking northeast. Fall 2023, Google streetview.

It’s worth slowing down time a bit to be able to see and explore the chapters here, which run back through commercial retail and early neighborhood development to wide open fields of berries and orchards, further back through the homestead era and even down slope toward the Columbia River and the slough wetlands that have been known and inhabited by Chinookan people since time immemorial.

This is the first of a three-part exploration to spark your imagination about the layers of history here. In this first installment, we’ll overview the arc of the story. In the second installment, we’ll take an illustrated deep dive into the subdivision years between 1900-1940 when everything was changing for the neighborhoods around the crossroads. Our last installment will explore the changing look of the intersection itself from the 1950s-1980s: gas stations and mom-and-pop groceries, greenhouses, a Safeway store, a trailer park, Adams High School and more.

Today, both NE Killingsworth Street and NE 42nd Avenue are well-used surface streets in the Northeast quadrant of Portland. The traffic-controlled intersection where they cross—poised at the northern edge of the 42nd Avenue / western Cully neighborhood commercial area four miles from the downtown core of the city center—features restaurants, bus stops, a convenience store, direct access to a city park and a brand-new workforce training center operated by Portland Community College. In fall 2025, Home Forward will open 84 units of affordable housing here. This is a busy place.

Early slopes above the Columbia Slough

For millennia the uplands south of the Columbia Slough and Columbia River were covered by a mixed forest of Douglas-fir, hemlock, cedar, alder and maple. Periodic fires, windstorms and outbreaks of insects and disease created openings in the forested canopy. The upland plateau that would eventually become the vicinity of today’s NE 42nd and Killingsworth sloped gently down to meet a vast flood plain, which followed an east-west line at the foot of the slope traced by today’s NE Columbia Boulevard.

Situated between the bottom of the slope and the main channel of the Columbia River just to the north was an interconnected flood plain mosaic of wetlands, ponds, marshes and off-channel waterways. Chinookan seasonal gathering places and dwelling places thrived here for thousands of years.

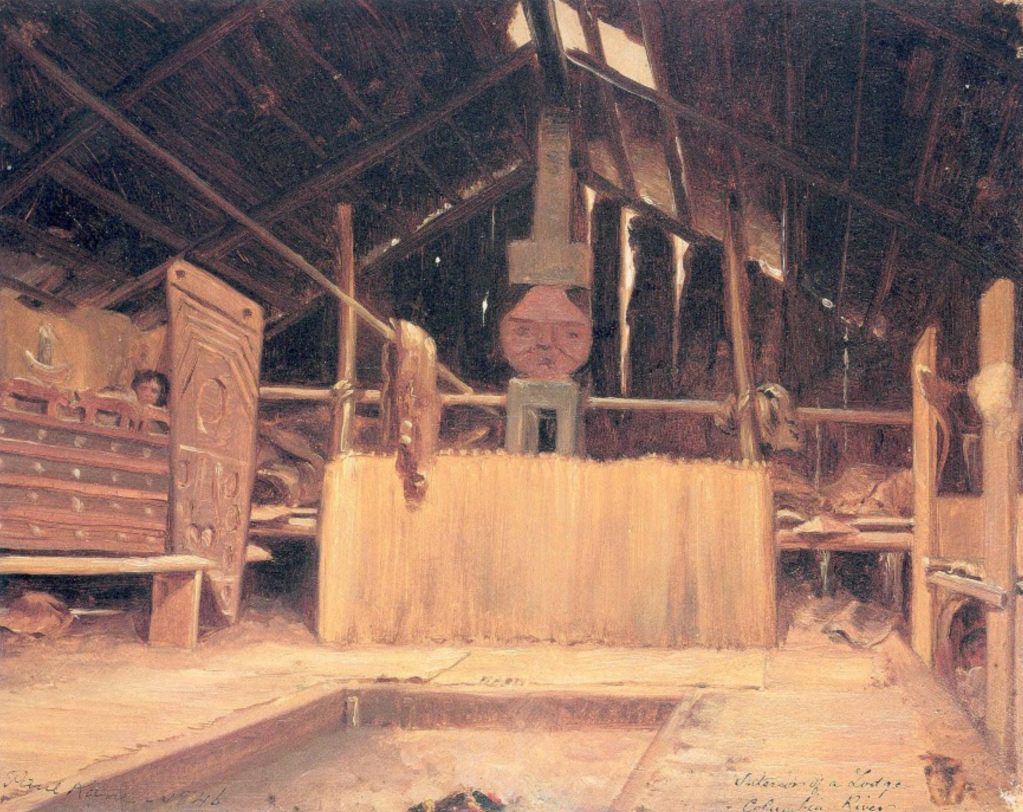

“Interior of Ceremonial Lodge, Columbia River,” an 1846 oil painting by Paul Keane, who traveled among the Chinook villages of the lower Columbia River.

Explorers, trappers and traders passed by on the Columbia River in the early 1800s intersecting the lives of indigenous people who had known this area since time immemorial. Early white traders introduced successive epidemics of disease, disruption and depredation, and by the 1830s the Chinookan people’s settlements in this area and their ways of life had been dramatically changed. By the late 1840s, Oregon Trail settlers arrived in the area; this immediate vicinity was homesteaded by several families practicing a mix of agriculture, trade and subsistence. Forests were removed, roads were constructed, and homes and barns built.

Surveys gridded the land

With the opening of the Oregon Trail in the mid 1840s and arrival of an increasing number of outsiders seeking land for farms and homesteads, the U.S. Government established a systematic process to map and identify lands that had been mostly cleared of indigenous people that could be granted to newcomers. Survey crews got to work here in the Portland area in 1851 establishing the Willamette Meridian, a systematic grid of townships, ranges and sections across the territory and the Western U.S. that promoted the availability of lands.

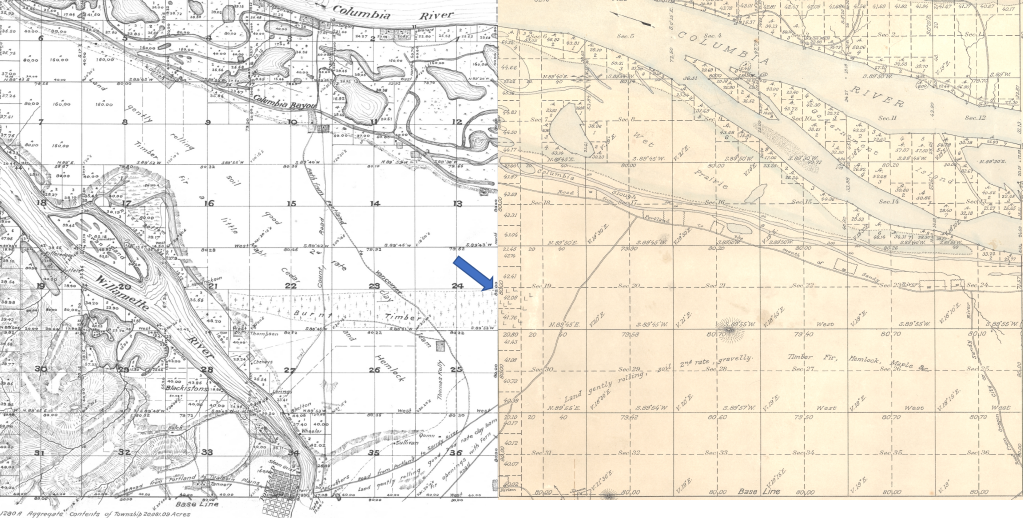

Today’s intersection of NE 42nd and Killingsworth exists at the corner of four sections of the Willamette Meridian: Township 1 North Range 1 East, sections 13 and 24 to the west; Township 1 North, Range 2 East, sections 18 and 19 to the east. Here is a compilation of those two original survey maps (click in for a closer look, they are fascinating). Observations below.

On the left is Township 1 North, Range 1 East. Notable are the early grid of a young Portland in the lower left; the location of past forest fires; the proximity of early trails and the complex waterways that make up the Columbia Bayou to the north. The blue arrow indicates the approximate location of today’s NE 42nd and Killingsworth. On the right is Township 1 North, Range 2 East. Notable here are the “wet prairie” description of the Columbia Slough bottomlands in the vicinity of today’s Portland International Airport; the road running northeast, predecessor of today’s Cully Boulevard; the surveyor’s descriptors—land gently rolling, soil 2nd rate, gravelly. Timber, Fir, Hemlock, Maple—describe vegetation in the area at the time; Rocky Butte shows up as the raised topography in the center of the map.

In October 1851, surveyor Butler Ives and his crew walked all through this area in order to draw these maps, and characterized what they saw like this:

Upland situated in the middle portion of the township is gently rolling and is elevated from 50 to 100 feet above the adjoining bottoms. The soil of the above is nearly uniform and good second rate clay loam and some gravelly in the northeast portion south of the Columbia bottoms.

The bottom lands both of the Willamette and Columbia, is from 5 to 15 feet above low water, the most elevated being along the banks of the rivers and bayous; they are subject to an annual inundation lasting from 1 to 2 months in the summer season, leaving only a few of the higher places dry. They are mostly open grassland. Soil rich alluvial and badly cut up with bayous, stagnant ponds and lakes which render nearly one half of them unfit for a cultivation.

The timber on most of the uplands is heavy and varies from 1 to 2 and in some instances to 250 feet in height. It is principally fir with a little maple, cedar, hemlock and dogwood interspersed.

The undergrowth is vinemaple, maple, brush and is usually thick; there is considerable dead and fallen timber caused by fire which has run through most of this Township.

In the bottoms is ash, willow balm, Gilead, crabapple with oak, and is found skirting the banks of the rivers and bayous. The undergrowth is in thick mixture patches of hardwoods, rose bushes gooseberry bushes and vines. The Columbia bayou is deep in most places and will admit boats drawing several feet of water. The other bayous are generally shallow.

As more people arrived, the surrounding lands were further divided, sold and developed. Wetlands to the north were drained for agriculture. More roads were built and active steamboat commerce developed on the nearby Columbia River. In 1882, a short stretch of dirt road in the growing nearby town of Albina was dedicated as Killingsworth Street, named for prominent real estate developer William Killingsworth. One year later—1883—the Oregon Railway and Navigation Company opened an east-west rail line passing nearby to the south that connected Portland with a growing network of regional and national railways.

A patchwork emerges

Our crossroads was well outside the eastern boundary of East Portland, which in 1891 consolidated with the towns of Albina and Portland (on the west side of the river) to form the single City of Portland. A rough north-south gravel trace known as the County Road (today’s NE 42nd Avenue) was carved out connecting the east-west predecessor of today’s Fremont Street with the east-west road along the Columbia Slough (today’s Columbia Boulevard). Growing population and commerce continued to boost Portland’s expansion. By the turn of the century, lands that 50 years earlier had been taken from indigenous people and deeded by the federal government to a handful of incoming families were being subdivided and sold into hundreds of parcels.

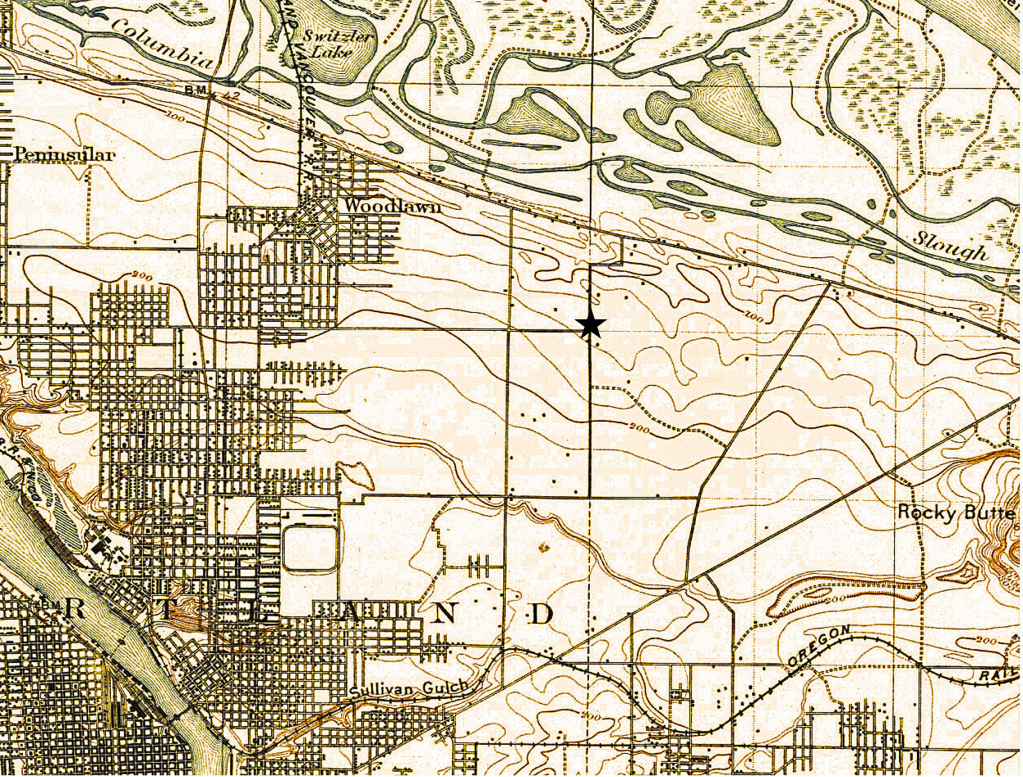

A patchwork of agriculture and development dotted the surrounding landscape with small farmsteads of orchards, berries and vegetables interspersed with homesites. Below is a detail from a USGS 1897 map of the area (star shows location of NE 42nd and Killingsworth). Notable here is that Killingsworth does not go farther east; development does not proceed much farther east than NE 7th; scattered farmsteads occupy the area of today’s neighborhoods; the Irvington race course at NE 7th and Fremont shows up in lower left.

Because of the area’s distance from the downtown core, its location beyond easy access to the streetcar system which promoted development, and its agricultural productivity, the crossroads remained largely rural until the opening of Portland Airbase in 1941, which was then a brand-new facility built on the reclaimed floodplain wetlands just south of the Columbia River.

Post-war boom ignites interest

The wartime expansion of manufacturing, residential growth and military operations drew new attention to the area, leading to transportation improvements and northern extension of NE 42nd Avenue with a viaduct over the Columbia River Highway, making it a major throughway from the eastside to the airbase. Residential and commercial development followed. Portland’s post-war housing boom in the 1950s led to further development, including more subdivisions, construction of a busy trailer park at the northeast corner of the intersection, and city acquisition of remaining nearby farm lands into what would become today’s Fernhill Park just to the northwest.

By the 1960s the area had been annexed into Portland proper. A commercial hub had developed at NE 42nd and Killingsworth including large and small grocery stores, service stations, bars, restaurants and light manufacturing. In the mid-1960s, the Portland School Board condemned a portion of the surrounding area to build John Adams High School, in direct opposition to residents’ wishes, razing homes and businesses. The school complex was later transitioned into Whitaker Middle School, and eventually torn down in 2006 due to changing student demographic needs and concerns about radon gas and the presence of unhealthy black mold found throughout the building.

Next: From farm fields to city lots – plats and development arrive

Very engaging research and commentary! Chris

What a fun article – I can’t wait for the next two installments. I grew up in this area and I even went to John Adams High School my sophomore year (for only two weeks – it was a “joke” of a school), but transferred back to Madison High School (now McDaniels HS). So many memories – thanks for the in depth writing and the great photos. I hope you have a photo of the Pink Patio, where I used to get a cherry Coke on my walk home from Whitaker Grade School. Dayna

Great work here! I’m anxious to see the next installments too.

We rented a cute bungalow in 1971 on 39th. In a funny “cutout” the Adams high school parking lot was on the north AND east side of our house! Some tall arborvitae shielded the view, ha. Don’t know why they were unable to take that lot, since you mentioned they managed to condemn so many other properties to build the school.

“Cut-outs” were single-house properties whose owner had refused to sell so the commercial developer would have to work around the home property. Can you imagine living in a small NE Portland house completely surrounded by a Fred Meyer’s store? The stubborn old owner finally died, of course, and FM quickly bought the house, tore it down and made FM “whole” again.

Really enjoying this.

Well written and researched! Great extractions from the surveyors’ notes -probably our only written descriptions of this area in the early 1800s. “Interconnected flood plain mosaic…” is an apt description of what now remains as the Columbia Slough.

Chinookan seasonal villages were sited on the Columbia River where they had access to waterfowl, aquatic life, trade, a transportation corridor, burial islands and nearby wetland plants.

The artist whose painting depicts the interior of a Chinook or Chinookan lodge was Paul Kane. We have him to thank for the few images we have of the local indigenous folk pre-white settlement.

The Public Land Survey System, devised by a committee headed by Thomas Jefferson, created grids across America to map the land, as Doug has described. But because the earth isn’t flat, the system had to create many different grids. Each grid is defined by its north/south axis; the one for Oregon and Washington is known as the Willamette Meridian. Surveyors started their work by establishing the origin of the north/south and east/west axes to the grid. That origin point, the Willamette Stone, is in the West Hills. The township in which our NE 42nd Avenue and Killingsworth lies is 1 north and 2 west of the origin or datum point.

In Butler Ives’ and other surveyors’ descriptions of the land is an odd expression, Balm of Gilead, an old Biblical term that we now know as cottonwood. Also mentioned are white ash, crabapple, elderberry and undergrowth briars.

Great article. And I’m just discovering this website, full of old Portland info. Thanks! This got me curious about where the house I grew up in is on that 1897 USGS map of “East Portland”. I was able to figure it out because the section of 45 degree streets in Woodlawn are unchanged since 1897…very cool. and a very useful landmark connecting the old map to modern.

Hi Greg. Glad you are enjoying Alameda History…many opportunities for exploration. You might enjoy seeing the many other historic maps that are available from Portland City Archives, some of which you can find on Vintage Portland, which is a great history feed from City Archives of photos and maps: https://vintageportland.wordpress.com/category/map/

p.s., does anyone know how to get the sales/ownership history of a house prior to whatever is listed on the County Assessor’s website? The Assessor lists the first owner of the home I grew up in as my parents, but it only says when they sold it (1986); there is no entry for when they bought it (circa 1965).

Just curious!

Hi Greg. It’s not a complete transaction history, but you can use Portlandmaps.com to look up specific addresses. Enter the address, click on “Assessor Detail” and you’ll get at least a partial look at sales history. Depending on how many times the house has changed hands, you may be able to see back 30-40 years. If you are seeking a comprehensive listing of all transactions since the houe was built (and before, when the developer acquired the property and even when it may have been part of a homestead Donation Land Claim), you can hire a title company to prepare a title report or abstract of title that captures information about buyer, seller and any easements or conditions placed on the property.

Doug, thanks, as always for your good work and an excellent article. Most fascinating to me is the 1897 map. It’s amazing how quickly the open Irvington area filled with new development in the next 25 years. The scattered housing just west of 33rd and north of Broadway is interesting, as this area had active farms, orchards and dairies. The homestead and farm of William and Hannah Dryden appears where the future NE Thompson and 28th would be. They began homesteading in the 1870s and continued until about 1910, when East Irvington and Bowman’s Addition replaced them. Also noticeable is the farmhouse at 28th and Knott where their son William H. Dryden Jr. lived and farmed.

A really wonderful description! I so appreciate that you don’t start with the coming of Euro-Americans.

Thank you so much for the research you did to write this! It’s really fascinating to learn more about this intersection I pass through almost every day.

Where did you find the old maps that you referenced?

I live close by, on 37th Ave (right across from Fernhill Park) in a home that was built in 1956. I had assumed the area was previously farmland since there is a lack of big trees once you are east of 33rd Ave.

Looking forward to Parts 2 and 3!

Thanks for the note Tobias. The survey maps can be obtained from the Bureau of Land Management, which holds all of the records relating to the former Government Land Office. It takes patience and trial and error to learn how to maneuver the website (which is loaded with data and very helpful once you figure out how to use it). Check it out: https://www.blm.gov/or/landrecords/survey/ySrvy1.php

Hope you’ve read the piece on Fernhill Park (https://alamedahistory.org/2017/04/22/fernhill-park-from-wild-thicket-to-popular-neighborhood-park/). Links in that post to other stories related to your environs. Part 2 to follow soon.

-Doug