To really understand the next installment of photos from the 1913 collection, it helps to visualize what the middle part of Portland’s eastside looked like then, and what was going on in the economy and life of the city. Following the Lewis and Clark Exposition, which put Portland on the map in so many ways, our population exploded: from 90,426 people in the 1900 census, to 207,214 by 1910.

Like shock waves rippling out across what had been a mostly agricultural landscape, development pressures began to reshape the dirt roads, orchards, dairies and forested clumps of the middle eastside. Meanwhile the economy began to heat up in the early teens as speculators, home buyers and homebuilders jockeyed to take advantage of the growing marketplace. Maps and a few precious photos from the early 1900s show this place as mostly undeveloped open lands, dotted with barns, scattered farm houses and dirt roads.

By 1913, the fields and hills of the middle eastside had been platted out into subdivisions, and the infrastructure of sewer, water, electricity and roads was trying to catch up with the vision sold by developers. In some places, a grid of streets existed, and a sprinkling of single family homes was being built, making visible the conversion from agriculture to residential use. To the north closer to Alberta, construction had been underway since the middle of the 00’s. Eastside neighborhoods closer to the river–Albina, Irvington, Ladd’s Addition, Woodlawn, the Peninsula–had been platted and growing as early as the 1890s.

Back in the day, the intersection of NE 33rd and Fremont–the focal point of this 11-photo series of glass plate negatives from City Archives–was a north-south wagon road to the Columbia River, and access point for the giant gravel pit near the top of the ridge. Surrounded on all sides by planned development, the intersection was in transition from dirt path to thoroughfare.

On the northeast side of the intersection, the Jacobs-Stine Company was ready to sell you a lot in the Manitou Subdivision. Just across Fremont to the southeast, the Terry & Harris Company wanted you to see the lots in Maplehurst. Our photographer from the Department of Public Works captured both views. Meanwhile, the mud puddle in the middle of the intersection reminded everyone the reality that for the moment, this was still a fairly rural place.

Looking to the northeast along Fremont from the southwest corner of NE 33rd and Fremont (33rd is passing from upper left to lower right). The house in the distance at right is today’s 3415 NE Fremont (built in 1912). Curbs and sidewalks are in (thanks to Elwood Wiles and Warren Construction), and ceramic sewer pipe is stacked near the curb awaiting installation. The Jacobs-Stine Company, boasting on its sign of being “The largest realty operators on the Pacific Coast,” was owned in part by Fred Jacobs, who would later die when his car tumbled off Stuart Drive in Alameda a few blocks from here, giving rise to the nick-name of that street as Deadman’s Hill. Photo courtesy of City Archives, image A2009.009.3613.

Looking to the southeast from the northwest corner of 33rd and Fremont. 33rd runs down the hill on the right. Fremont follows the slight rise to the left as it heads east. Sewer construction is evidently about to begin. Photo courtesy of City Archives, image A2009.009.3614.

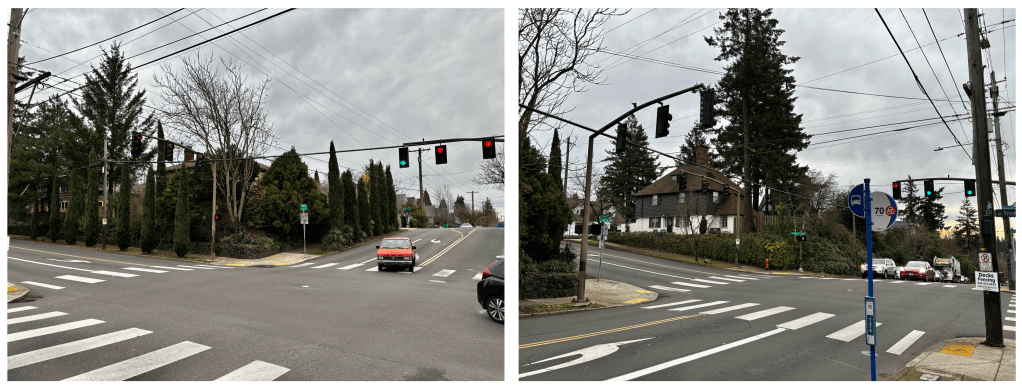

Left photo is similar to top, looking northeast. Right photo is similar to bottom, looking southeast.

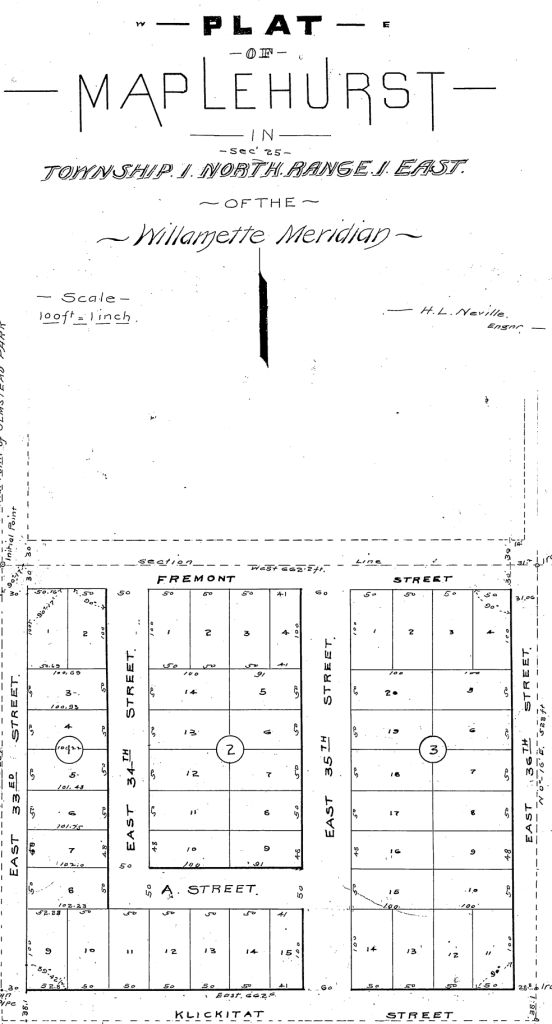

Maplehurst was platted in 1910 by Mary Beakey, who named a street for her family (labeled as A Street on the plat). It’s a relatively small subdivision–only three blocks and 43 lots, and exists up against a plat called Irene Heights, which was developed by the Barnes family, containing the Barnes mansion and multiple former Barnes family homes.

NE 33rd wasn’t the only north-south thoroughfare passing through a landscape in transition. One half section to the east (our landscape was gridded into sections, townships and ranges by surveyors in the 1850s), NE 42nd Avenue was experiencing its own growing pains.

Up next: The Alameda stairs. Our Department of Public Works photographer captured the brand-new stairways transiting the slope between Fremont and Alameda Terrace (known as Woodworth before the Great Renumbering of the early 1930s).

I think there is more than one deadmans hill in the area one that drops down from Alameda to Fremont about 26th another from Alameda down to Sandy by the Reinlander about 55th and I would throw in 39th from 41stdrive to Stanton

Undoubtedly other hills named “Deadman” in many neighborhoods with steep slopes. Stuart Drive in Alameda, sadly, has a documented story related to the demise of Fred Jacobs. https://alamedahistory.org/2010/11/22/the-story-behind-deadmans-hill/

It’s evident there was virtually no old growth timber in the area. Very early maps show what became known as Alameda Ridge had “burnt timber.” No indication whether it occurred naturally or was done intentionally to clear land. Do you know, Doug?

The actual survey notes from 1851, handwritten by Government Land Office Surveyor Butler Ives, reports: “this is good soil, clay loam, some gravelly in section 25 & 36 [south of today’s Alameda ridge, from Fremont to Stark], lightly timbered and gently rolling. In Section 13 & 24 [north of the Alameda Ridge between Fremont and Columbia Boulevard], there is a fine thrifty growth of fir but has been killed by fire in some places and the land has a gradual descent to the north, the Columbia bottoms, which occupy the northern part of the township.”

While there may not have been any established stands of old growth observed at the time of the survey, there surely would have been over the long reach of time, just given the very favorable soils and climate, and the prevalence of Douglas-fir in this region.

Thanks for clarifying that, Doug.

What an extraordinary service you provide to people who live, work, and grow up in Northeast Portland! It’s wonderful to imagine what our neighborhoods were like over 100 years ago

I wish I’d paused to photograph the old brick paving on NE Fremont St. on the steep portion of the road just west of NE 33rd Ave, last summer when the city was repaving the street. Maybe someone here snapped a picture? It was a beautiful sight to see. Once more covered up with asphalt!