Last in a four-part series on the history of Sullivan’s Gulch

During the Great Depression and the war years of the 1940s, Portlanders had more pressing things to think about than the future of Sullivan’s Gulch. If they thought about the gulch at all, it might have been about their jobs at Doernbecher’s furniture factory, or an escape to Lloyd’s golf course, or the sprawling Hooverville-shantytown at the mouth of the gulch.

Before the speedway: looking west down Sullivan’s Gulch through the Lloyd Golf Course, just west of the NE 21st Avenue viaduct, December 1947. The driving range fence and a corner of Benson High School are visible in upper left. Photo courtesy of Oregon Historical Society, OrHi 91595.

Through those tough years, many families and small businesses struggled just to make ends meet. A quick look at the census shows how many homes on the eastside took in a boarder or two, or had extended family living under the same roof. And if you were a citizen of color or an immigrant, the Portland establishment was more about keeping you down than helping you up.

An influx of workers associated with shipyards and the World War 2 effort brought continued growth particularly on the eastside, and further industrialization along the Willamette and Columbia rivers. Between 1920-1950, our population increased by more than 115,000 people.

Many of those people had cars.

Completion of the Ross Island and Burnside bridges in the mid 1920s allowed direct access to downtown from the eastside. The Ross Island Bridge, completed in 1926, was the first major Willamette crossing that did not include a streetcar route, an important choice and signal of things to come.

By the late 1920s, automobile use had outpaced streetcar ridership and east-west arterials were increasingly clogged with car commuters morning and night. Between 1913 when the Broadway Bridge opened and 1928, the total number of automobile registrations in Oregon increased from 10,165 to 256,527. A powerful force had been unleashed that was going to re-make the landscape.

Another indication of our early car-related growing pains: in 1927 voters approved a street widening levy that literally remade Burnside Street by removing entire portions of buildings and adding street lanes to cope with increased traffic. Similar work took place on Northeast Broadway in the early 1930s.

Looking west at NW 6th and Burnside during the widening project. Buildings on both sides of the street were cut back to make way for more lanes and more traffic. This was not a popular move as Portland struggled with growing pains. Photo courtesy City of Portland Archives, image a2001-062-2

Despite these changes—or perhaps because of them—City Council received an increasing number of complaints about traffic on Fremont, Broadway, Burnside, Stark and Hawthorne. The writing was on the wall for a bigger traffic congestion “fix.”

In 1944, City Commissioner William Bowes brought up C.A. McClure’s earlier Planning Commission speedway vision. The State Highway Commission—chaired by T. Harry Banfield—was on board and suggested the city not grant any more building permits along the Sullivan’s Gulch right of way. If the speedway vision was going to come to pass, it was time to stop allowing development along the edges of the gulch. By agreeing, Portland inched closer to endorsing the project.

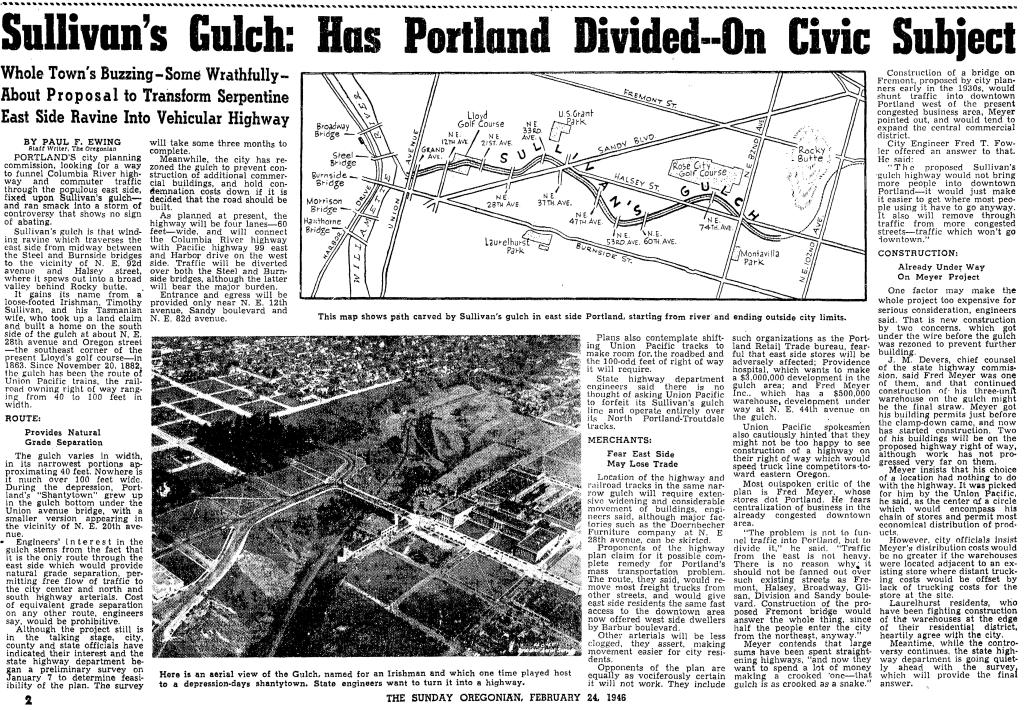

As the war years ended, the topic rose to the top of Portland civic life and news coverage.

From The Oregonian, February 24, 1946

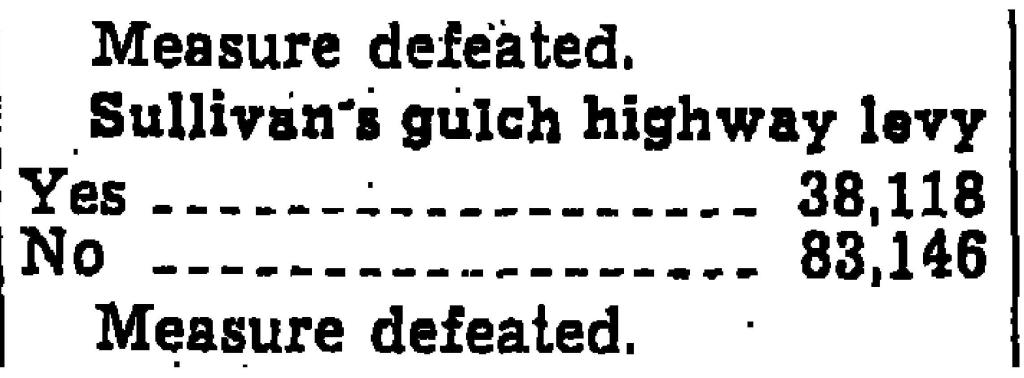

City Council placed a money measure for the expressway on the May 21, 1948 ballot asking if Portland voters were ready to pass a $2.4 million tax levy for the city’s share of a $10.5 million project to build a gulch expressway that would theoretically ease traffic problems. Interestingly, also on the ballot that day was a city ordinance requiring the leashing of all dogs…council didn’t want to be alone with just its fingerprints on that explosive decision either.

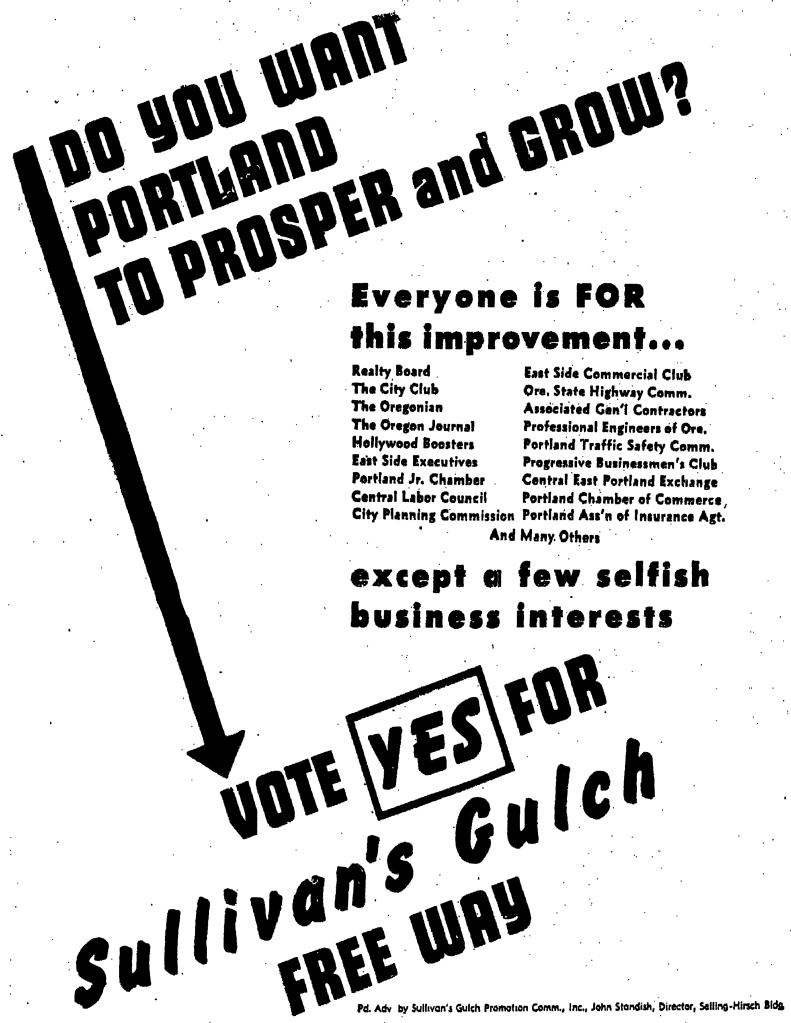

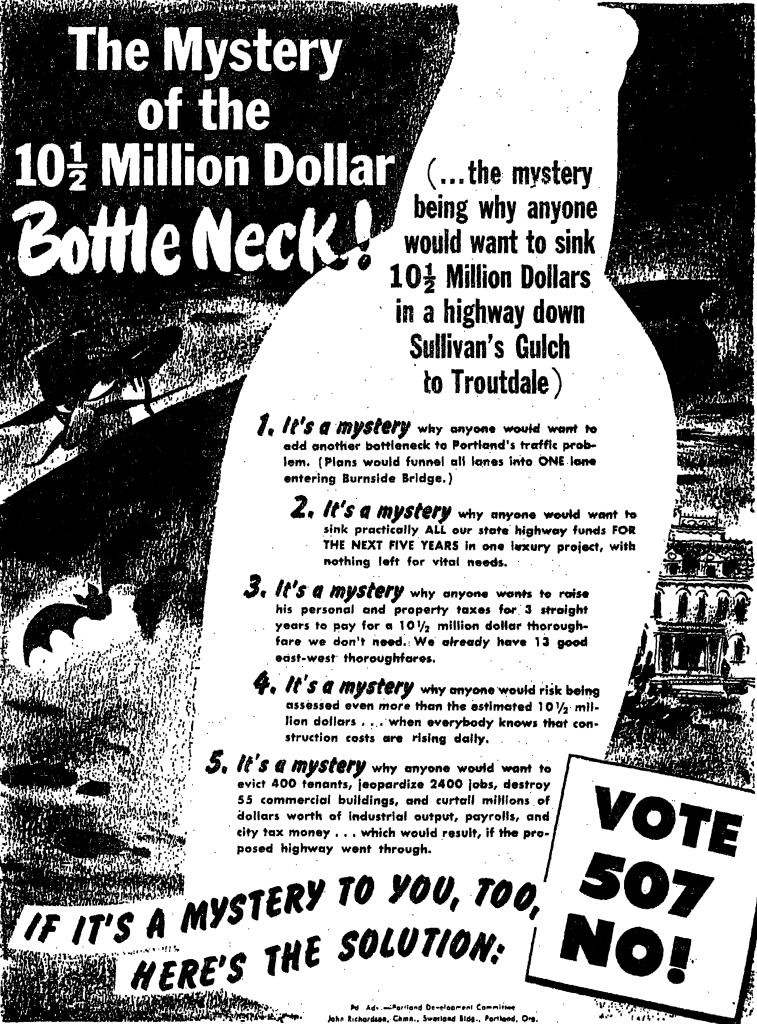

The resulting public dialog and advertising campaign about the expressway levy produced fireworks as people and businesses chose sides:

From The Oregonian, May 20, 1948

From The Oregonian, May 19, 1948

Portland City Club added its voice and recommendation with a report considering the pros and cons of the expressway, including an awareness for Portlanders that construction would require demolition of more than 110 homes along the right-of-way.

The results of the vote were an unequivocal no: Portland was not interested. (Results of the dog leashing ordinance were far less clear: it was defeated by a mere 4 percent margin).

From The Oregonian, May 24, 1948

But the establishment was strong and within a week, the Oregon Transportation Commission went ahead anyway with survey and planning work to prepare for major right-of-way acquisition. Spurned by Portland voters, T. Harry Banfield and the commission decided to look elsewhere to fund the speedway vision.

During the week after the landslide vote, The Oregonian editorial board expressed its surprise about the Highway Commission’s decision to go ahead anyway, but endorsed the new highway as necessary for progress:

From The Oregonian, May 27, 1948

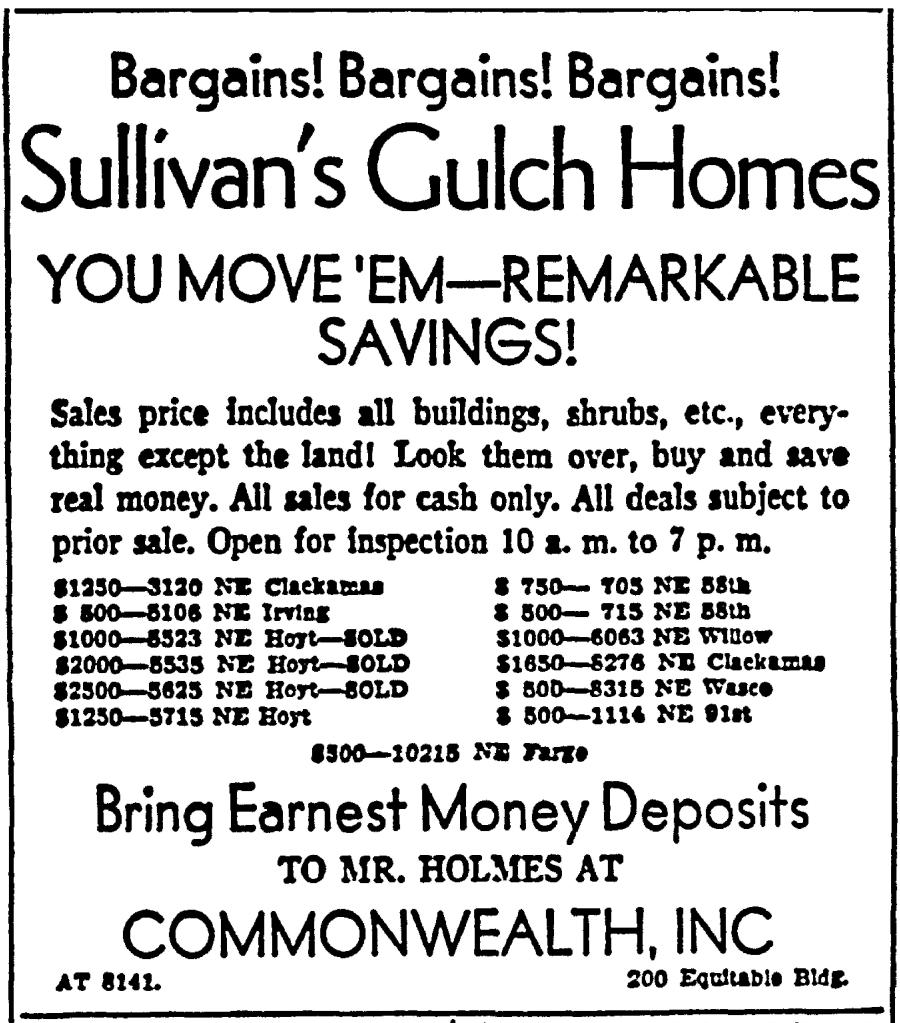

Soon, things began to happen, with tangible progress beginning to show on the eastern end of the project and then proceeding west toward downtown. Portions of neighborhoods were bought and houses moved or demolished:

From the Oregon Journal, August 21, 1949

Later in 1949, the Highway Commission had to revise right-of-way acquisition costs upward from $2.4 million to $4.8 million. In August 1950, T. Harry Banfield died while on a fishing trip in Gold Beach, but the vision was well on its way into implementation. By early 1952, the first construction contract for grading at the far eastern end of the highway in the Fairview area had been let for $400,000. In March of 1955, the Doernbecher factory in the gulch at NE 28th Avenue closed and its furniture-making machinery sold at auction. In January of 1956, seven of the Lloyd Golf Course putting greens were sold to Riverside Golf and Country Club for an undisclosed price.

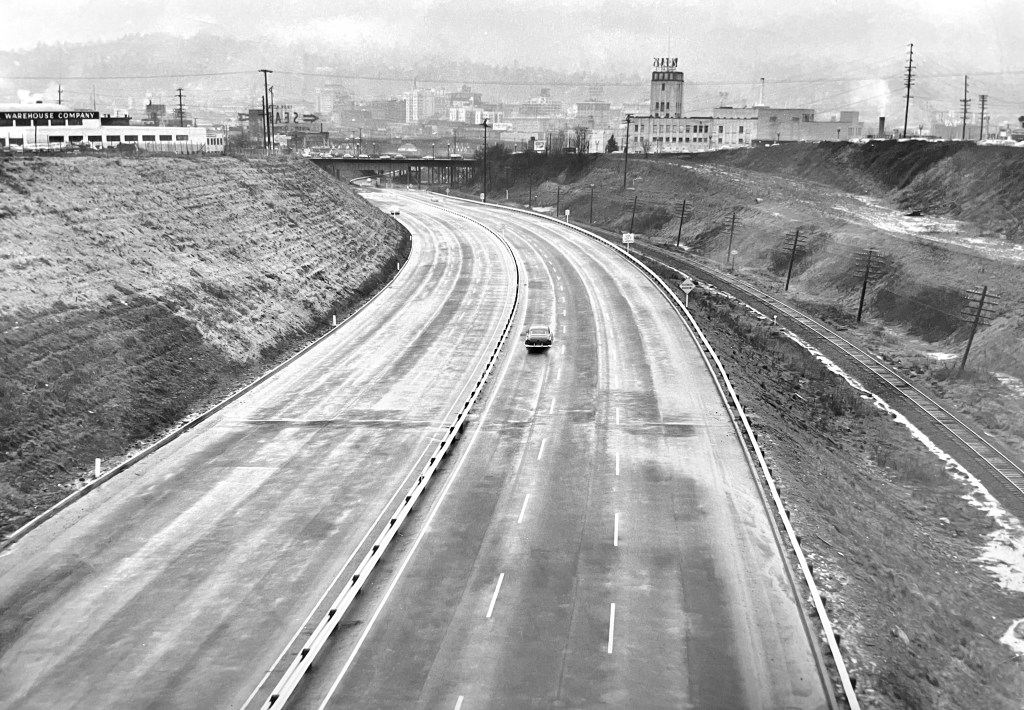

Photos from the 1950s make it clear just how much gulch-widening and dirt moving would be required, particularly in the big bends between NE 21st and NE 37th.

On October 1, 1955, the highway opened between NE 42nd and Troutdale. Two years later, with funds from the major highway infrastructure bill signed into law by President Eisenhower, the final two miles were completed. By 1960, the Banfield Freeway was fully operational and a century of transformation in the gulch was complete, from natural area to homestead to manufacturing hub, golf course and shantytown.

Despite all the changes brought about by the speedway vision, some weren’t quite ready to embrace the gulch’s new identity. A grass-roots campaign that began (and ended) in Parkrose attempted to claim local history, reminding us once again about the importance of places and their names.

Today, it remains the Banfield. But some of us know it’s still Sullivan’s Gulch.

great piece… you’ve probably seen this picture before but it shows the fill added to move Lloyd Blvd south in 1958/59

https://photos.app.goo.gl/vW6vmZMrx4MjJgaT6

Thank Jim. Yes, that’s a classic view. So many truck loads of good dark fill up there on the bench to the left. Mind boggling how much dirt has been moved around to make the gulch what it is today.

That fill was placed over sewers that were not designed to be that deep. The 1911 sewer failed in ’96 and created a sinkhole that closed Lloyd Blvd. for months. There is also a 1950s sewer under the fill that has sagged and doesn’t flow properly. It created problems for the designers of the new Earl Blumenauer bridge too. The gift that keeps on giving. These things get really political. The folks who benefitted from the road realignment didn’t bear the cost to the ratepayers.

Very interesting. I have a photo from the 19-teens of the major trunk sewer that was laid down the gulch and it was a giant piece of work, which apparently left a legacy. In the photo from 1947 (at the top of the article), do you know what the rectangular pond was all about? It appears in this photo surrounded by a fence. it shows in earlier photos as well. A well or pond of some sort?

Doug, I assumed that rectangular concrete structure was from the golf course era. A section of the 1912 sewer between 13th & 18th avenues was replaced about 15 years ago. The contractor excavated a number of abandoned footings in the process.

This is a wonderful piece of work. The story unrolls cinematically. The jump in car ownership between the 19 teens and the very late 1920s was true in so many cities, and with similar (destructive) results. Futurama was just around the corner….

So interesting! Thanks for capturing this piece of Oregon history.

Excellent series, Doug. Thanks!

Thanks Mark! Keep walking…