Third in a three-part series

As Portland slowly rebounded from the Great Depression of the early 1930s and interest rekindled in Portland residential real estate, the stage was set for a new era at NE 42nd and Killingsworth. Open lands were available for development, subdivisions were platted with buildable lots ready to go, and new infrastructure was on the way in the form of paved roads and big plans for the new Portland Airport. A small wood-frame general store had been built in the late 1920s at what was then the quiet rural crossroads, and other nearby mom-and-pop stores were opening to meet the needs of surrounding residents.

By 1951, the corner was home to multiple gas stations, a barber shop, a cleaners, an ice cream shop and a café. The small wood frame building on the northeast corner had become the Publix Market, operated by Cliff and Mary Tadakuma. Here’s a look:

1951 Looking Northwest

Looking to the northwest at the intersection of NE 42nd and Killingsworth about 1951. The Publix Market is at the northeast corner, on the right. The Lyle Sumner service station is on the Northwest corner. Note that the intersection is not signaled. Photo courtesy of Joyce Tadakuma Gee.

Before the war, Portland had a thriving population of immigrant and first-generation Japanese families who were integrated into all aspects of civic life. In early 1942, following the attack on Pearl Harbor and declaration of war, Japanese Americans were forcibly removed from most West Coast cities and relocated to internment camps in remote inland areas of the American West. The federal policy fractured families physically and emotionally, and resulted in significant economic losses for Japanese-Americans who owned businesses and property.

As families were loaded into buses and trains during the “evacuation,” heart-breaking decisions were made about the disposition of lands and businesses. Beginning in the 1930s, the Shiogi family had operated a market known as “Publix Market” at the corner of North Killingsworth and Gay Street in North Portland (the storefront that today houses Milk Glass Market, 2150 N. Killingsworth). When the Shiogis were removed to the Minidoka Internment Camp in Idaho, they “gave” their store to neighbors for safe-keeping.

In the fall of 1945, upon returning after the war, the family attempted to re-open the store but found anti-Japanese sentiment in Portland to be too strong. Younger members of the family—daughter Mary and her husband Cliff Tadakuma—who had endured the internment experience only to be discriminated against at home in Portland, moved to Hawaii for several years in search of a more hospitable environment. Mary found work as a housekeeper. Cliff became a gardener on a large estate.

In 1950, Mary and Cliff Tadakuma—with their young daughter Joyce who had been born at Minidoka—returned to Portland from Hawaii and decided to try again to reopen Publix Market, but this time in a different location farther out Killingsworth, in northeast Portland.

Mary had grown up in Portland, a first generation Japanese-American. Cliff had grown up in Maui and graduated from Oregon State University with a degree in chemical engineering (and where the two had met). While their interests and expertise were not necessarily in running a small grocery store, it was a better option than housekeeping and gardening when they returned to Portland.

The couple leased the old wood frame building at the northeast corner of NE 42nd and Killingsworth. The store was adjacent to a densely populated trailer court established during the booming war years, and the surrounding residential neighborhood was growing as well. With the help of Mary’s parents Lori and Hood Shiogi who had run the market when it was located in North Portland, Mary and Cliff set about re-establishing Publix Market.

Daughter Joyce Tadakuma Gee was six years old at the time and recalls that her family lived in the back of the store. Behind the shelves and retail area were two small bedrooms, a bathroom a living room and a small kitchen. Joyce—who is a long-time Portland resident—attended nearby Whitaker Elementary School, located on Columbia Boulevard. “I remember being so envious of classmates of mine who had ‘real’ homes to live in,” she recalled when interviewed in 2020.

Neighbor Doris Woolley grew up on Jarrett Street just north of Publix Market, and remembered that everyone referred to the store simply as “Cliff and Mary’s.” Doris—who passed away in 2020 at age 92—recalled that all of the residents of the trailer park and neighbors north of Killingsworth were loyal to Cliff and Mary and would only shop at Publix Market, even though there were two other small markets nearby.

“It was a great store and they had pretty much everything you wanted,” Woolley recalled. “Plus, they would let you run an account. In those days a lot of people would charge their groceries during the week and pay for them once they got their paychecks at the end of each week.”

Asked about her recollections of Cliff and Mary’s Japanese American origins and any tensions during the post-war years, Woolley remembered only that everyone liked Cliff and Mary. “They were very kind to everyone.”

Mary Tadakuma died in 1954. Cliff remarried and moved with daughter Joyce to Hood River, where he ran a grocery market until his death in 1978.

1958 Looking North

This 1958 photo (courtesy of City of Portland Archives, a2005-001-984) looks north on NE 42nd just south of Killingsworth. Publix Market is gone, replaced by the Panarama, a liquidation store. The Chevron service station across 42nd to the west has changed hands since the earlier photo and was being operated by Rod Martin. Behind the Panarama Market was the parking lot and sign for the brand-new Safeway store. The intersection was controlled by stop signs facing NE 42nd Avenue.

The white clapboard market building was built about 1927 and was initially operated as a grocery store by Bill and Jennie Batson. Panrama survived the 1957 opening of Safeway, but by 1961 the building had been demolished and replaced by a parking lot and service station.

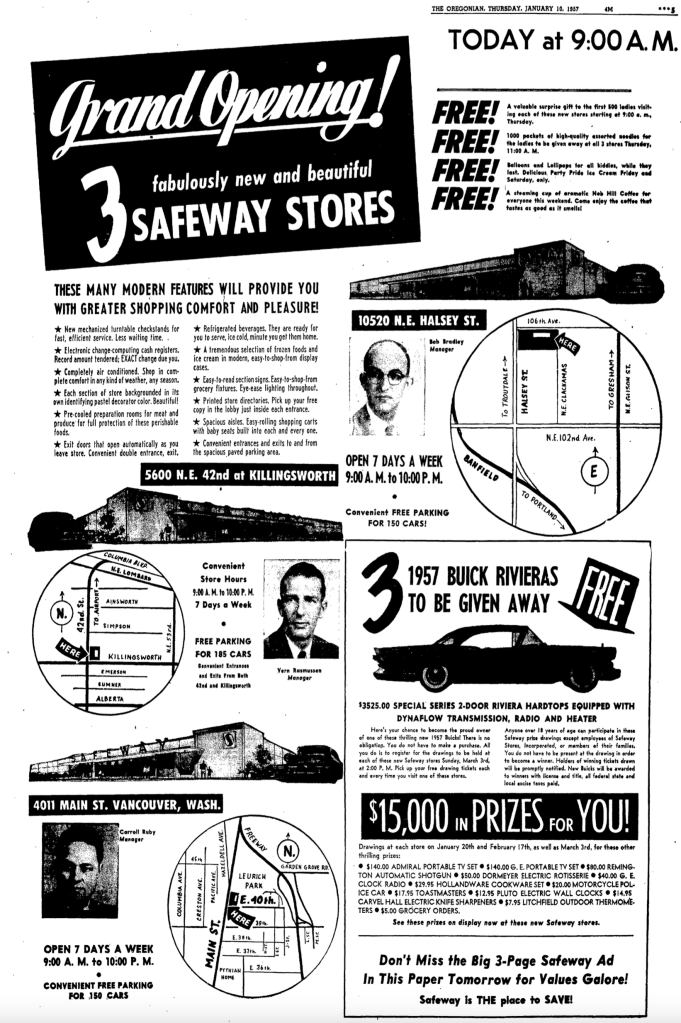

Safeway Opens in January 1957

A combination of changes in the grocery business—with tendencies to larger chain stores—and an increasing population and market made the corner a natural for the Safeway store, built on the site of what had been the trailer park and small grocery store in the 1940s-1950s.

The store opened in January 1957 as part of a three-store opening blitz in the Portland area, as described in this full page ad from The Oregonian on January 10 1957.

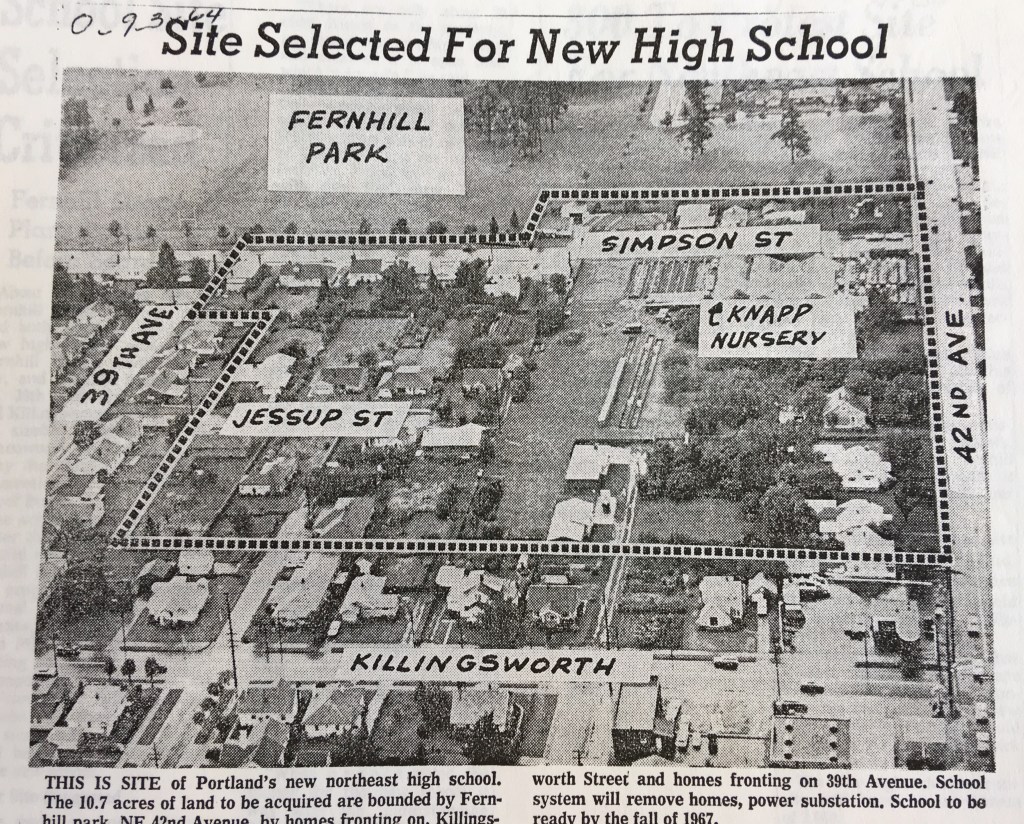

1964 siting of John Adams High School

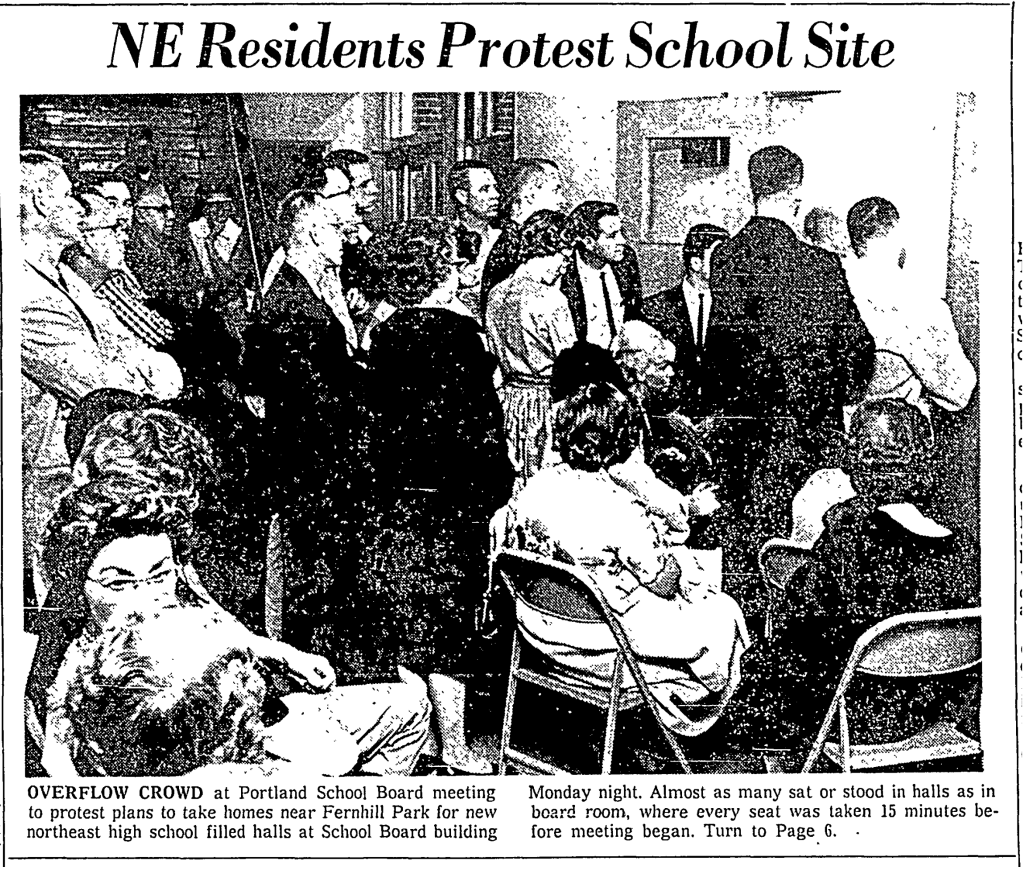

Construction of John Adams High School just southeast of Fernhill Park in the mid-1960s caused quite a stir and protest from the neighborhood. More than 200 angry neighbors turned out at a Portland School Board meeting on September 14, 1964 to share their disbelief that the School Board would demolish and relocate more than two dozen homes, three duplexes, a local greenhouse/nursery known as Knapps and a PGE substation to make room for the school.

From The Oregonian, September 3, 1964. The homes and businesses inside the dotted line were demolished or relocated to make room for John Adams High School.

From the Oregon Journal, September 3, 1964. Greenhouses for Knapp’s Nursery on NE Simpson are visible in the photo to the left, which looks north on NE 42nd.

The emotion and sense of loss in the letters and petitions submitted to the school board make for tough reading. Despite this strenuous protest, demolition went ahead, construction followed, and John Adams High School opened in September 1969.

From the Oregon Journal, September 15, 1964

A dozen years later, when high school enrollment dropped in the early 1980s, the building was repurposed as a middle school and operated for another 18 years before being closed in 2000 due to health concerns about mold and radon gas. The building sat empty and was frequently vandalized until being torn down in 2006 leaving the large open space south of the track. Newcomers to the area today might not even know that vacant piece of ground south of the track was once a high school and middle school.

1965 Looking South

This view from 1965 looks south along NE 42nd Avenue. The tall buildings in the background are the relatively new St. Charles Church. The intersection has a traffic signal, and each corner features a different gas station: Texaco, Hancock, Mobil and Chevron. The Hancock building stands about where the Publix Market building once stood. The Safeway sign looms large over the intersection. Photo courtesy Portland City Archives, a2011-013.

Safeway operated in this location until about 1972, when the property was acquired by Portland Community College and the building remodeled to become a workforce training facility. In 2024, a completely new PCC building at the corner is now the Portland Metropolitan Workforce Training Center. And construction is underway just to the east on an affordable housing development managed by Home Forward that will include 84 units.

From open space that once provided wildlife habitat and material needs for Indigenous people; to homestead and farm fields that supplied a growing population of newcomers; to park land, school grounds, green houses, family homes and retail; and today affordable housing, workforce development and some great restaurants; this place has continued to evolve, layer upon layer of history and of life.