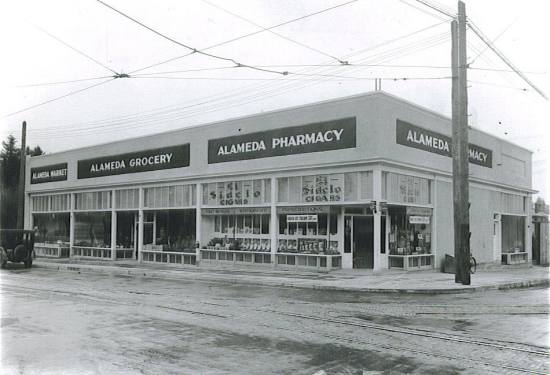

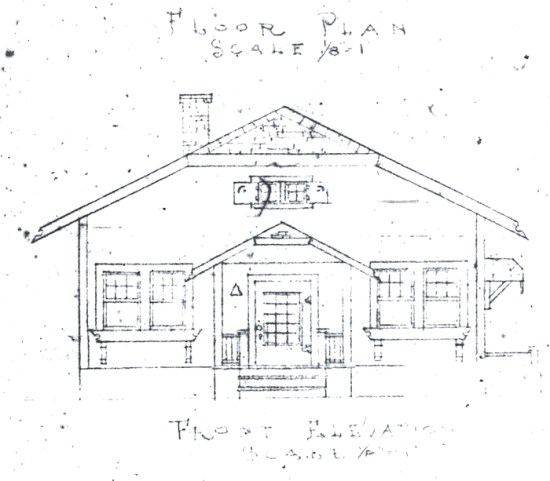

Looking southwest at the corner of NE 24th and Fremont, early 1920s. Note delivery bike visible behind power pole. OrHi 49061.

There was a time when the building we know today as the home of Lucca and Garden Fever—at the southwest corner of 24th and Fremont—looked after most of the neighborhood’s needs for grocery and personal goods. Alameda Pharmacy, Alameda Grocery, John Rumpakis’s Alameda Shoe Repair, even the dentist’s office, upstairs above the pharmacy, were neighborhood landmarks that everyone knew, shopped in, and pretty much took for granted (except the ice cream sodas at the pharmacy which were supposed to be legendary). The pharmacy and grocery even provided a delivery-by-bicycle option for homemakers who needed a few small items, but couldn’t get out of the house. It was a win-win situation for Alameda and for the local family-owned business during those early years.

To be sure, some shopping needs were taken care of away from the neighborhood. Even then, there were smaller markets or “convenience” style stores of the day located within walking distance (see this post on the Davis Dairy Store, one such locally-owned convenience market). Built in 1922 during the peak of neighborhood construction, the Alameda Grocery commercial building at 24th and Fremont quite literally had a corner on the market.

That is, until the mid 1930s, when a fully-built-out neighborhood with a growing population, combined with a slowly recovering economy and new trends in shopping, opened up new opportunities for big business which began to shape the corner.

Enter the Safeway Corporation: a publicly-traded rampant success story, with headquarters in Oakland, California and more than 3,200 chain stores nationwide. The company’s penetration of local grocery markets was so complete that by 1935, many states around the country were passing legislation—urged by local merchants who were getting slammed by Safeway chain stores—that taxed the huge company’s local operations to discourage competition.

But not in Portland. By 1937, Safeway had 54 stores here, including 46 stores located in eastside neighborhoods, and even one on the doorstep of Alameda at the southwest corner of NE 24th and Broadway (today it’s Brake Team, an auto service garage) built in 1936. Most of these stores were modest in size, and not like the sprawling stores we know today. Undoubtedly, the local Safeway on Broadway cut into the market share of Alameda Grocery. But nothing like what happened starting in 1938.

Click on the image for a larger view. This ad is from The Oregonian on September 13, 1940 announcing a remodel and reopening of the Alameda Safeway.

On July 16, 1938, Safeway opened a store in the building we know today as the home of Alameda Dental and Frontier Bank on the southeast corner of the intersection. The property had been leased from the Albers Brothers Milling Company, who incidentally also owned the Alameda grocery and pharmacy building across the street. Retail activity in the single-storey 50-by-100 foot concrete Safeway building began to take a big bite out of Alameda Grocery’s market share.

By 1940, Safeway expanded and remodeled, while Alameda Grocery across the street struggled to hold on. About that time, Safeway made plans to expand beyond the footprint of the existing store to take in the entire north end of the block. But as The Oregonian reported on March 20, 1942, the Portland City Council narrowly defeated a zoning change that would have allowed this major expansion. Despite voicing concerns about home values in the neighborhood, Mayor Earl Riley voted to expand the commercial zoning to permit the Safeway expansion:

From The Oregonian, March 20, 1942.

Safeway’s expansion into residential neighborhoods was not a phenomenon isolated to Alameda. Blog reader and longtime Grant Park resident John Hamnett writes that in nearby Grant Park, local residents fought a pitched battle with the City of Portland regarding a plan to build a Safeway adjacent to the Grant Park Grocery, a similar locally-owned market at the southwest corner of NE 33rd and Knott. The vision for that zone change took in all of the southwest corner, and further considered zoning the entire intersection commercial at all four corners. In May 1942, City Council voted 4-1 to allow the Safeway development. Incredulous neighbors protested time and again concerned about their property values, but the City would not relent. Finally, in March 1943, neighbors filed suit against the city for allowing the zone change, and won in a clear decision handed down by Circuit Judge Walter L. Tooze.

Back at NE 24th and Fremont, two gas stations were added on the northwest and northeast corners—the true portal of the Alameda Park subdivision (today site of a parking lot, and Perry’s on Fremont). Generational and ownership changes were remaking the anchor businesses on the south side of the street as well. Eventually, as Safeway’s business model changed (fewer, larger stores instead of the 50-foot by 100-foot businesses sprinkled all over Portland), the former Safeway store went back to being a family-owned business, loved and known by a generation of Alamedans as Brandel’s. Nature’s Fresh Northwest (or simply “Natures”) eventually took over the Alameda Grocery building. And today, after a string of unsuccessful restaurant tenants, Lucca seems to have hit its stride.

Check out this story from The Oregonian on January 17, 1984, which is a snapshot as the corner transitioned from some difficult times in the 1970s to the place we know today:

From The Oregonian, January 17, 1984. Click on the image for a larger view.

We still miss Brandel’s and the ease of slipping into that old Safeway building for a gallon of milk on the way home. But every time we pass through that intersection, we pause for a moment to think about how our neighborhood geography could have turned out quite differently.