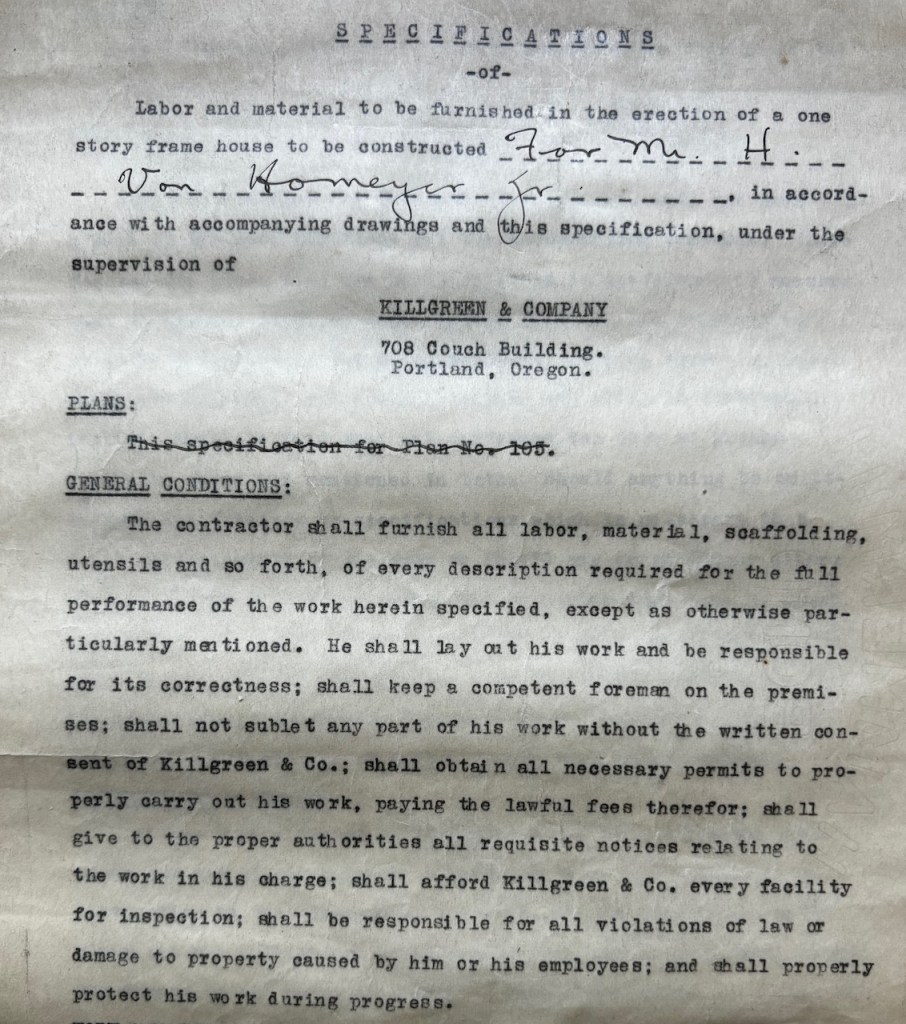

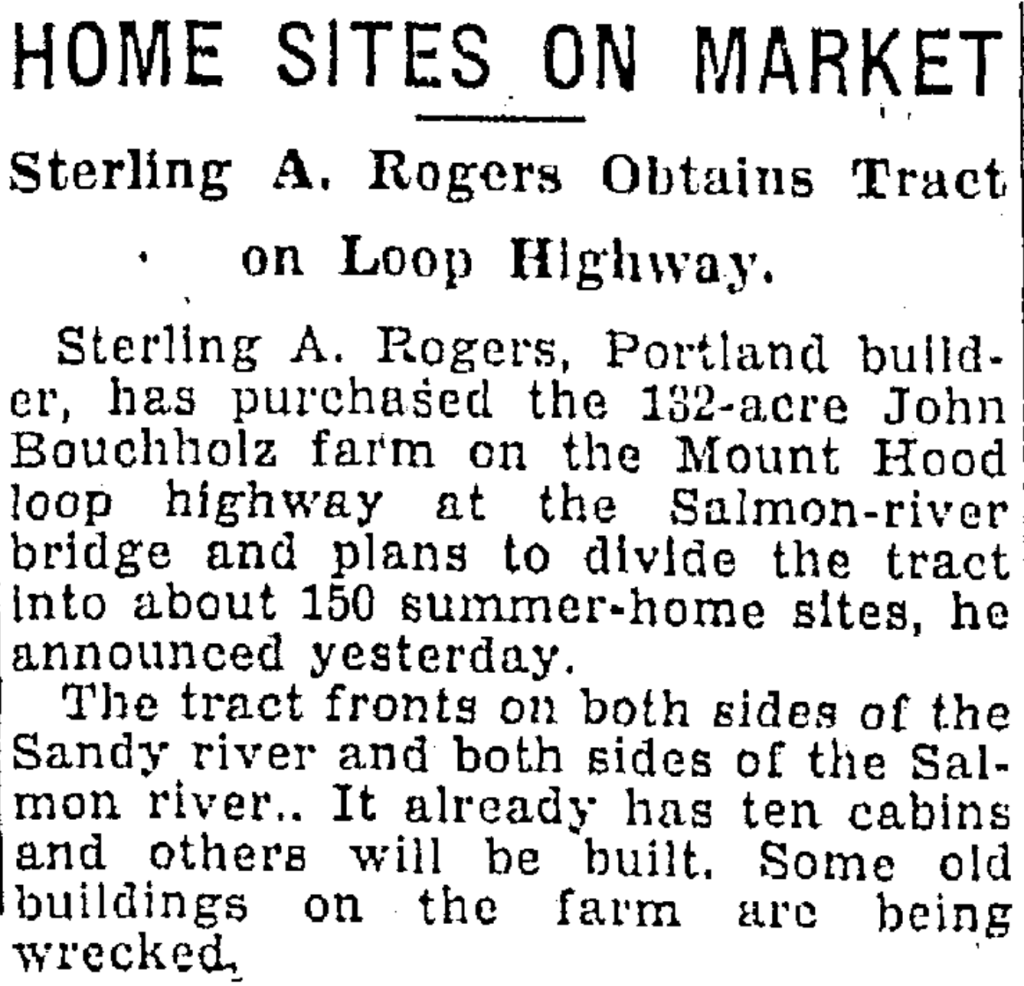

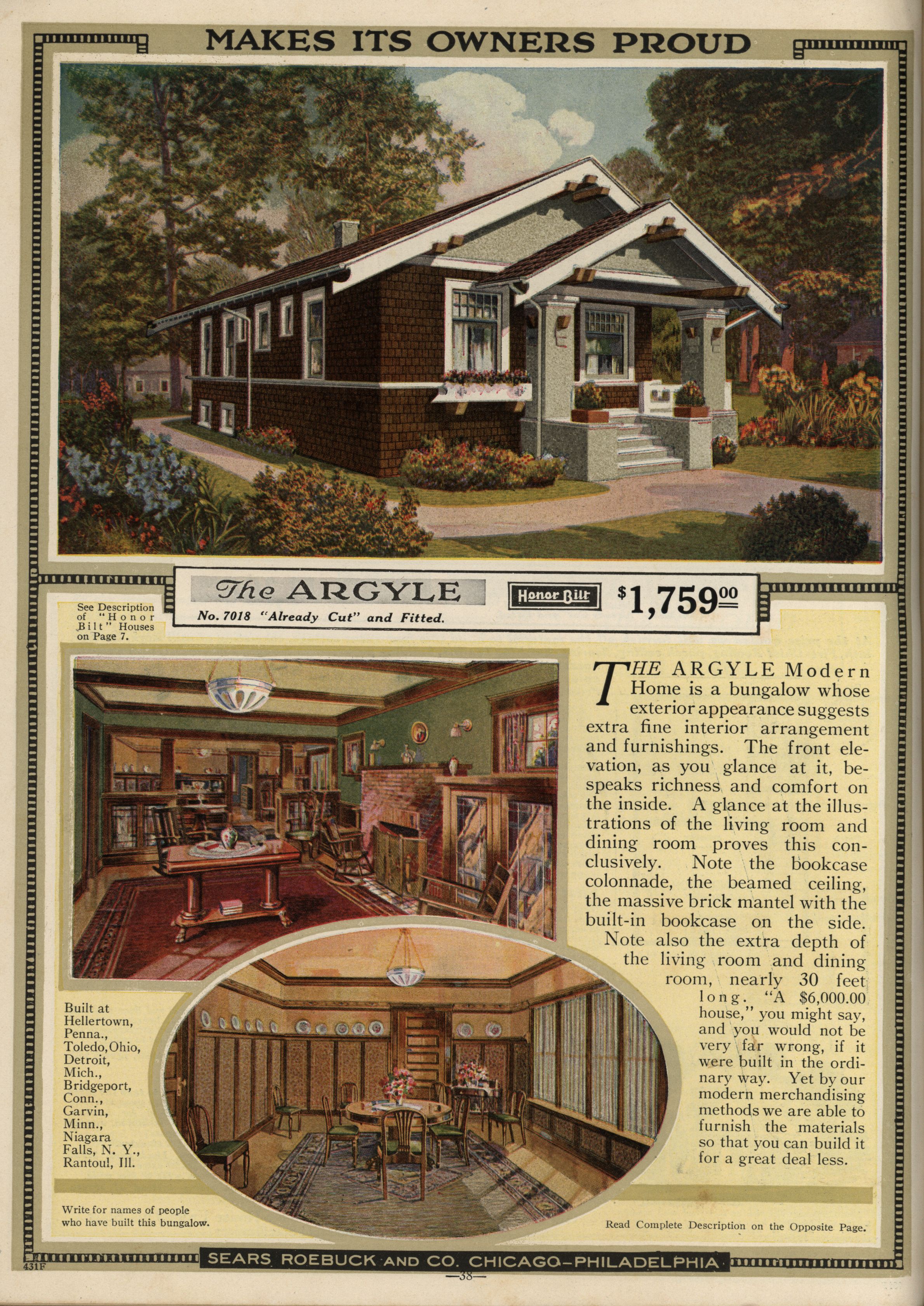

Neighbors interested in adaptive reuse of old buildings have had a front row seat this summer and fall as the von Homeyer house at NE 24th and Mason has been brought back from the brink of being a candidate for tear-down. Today, it’s on the cusp of its new life, with all of its systems transformed, spaces rearranged and upgraded, and virtually every interior and exterior surface either new or restored.

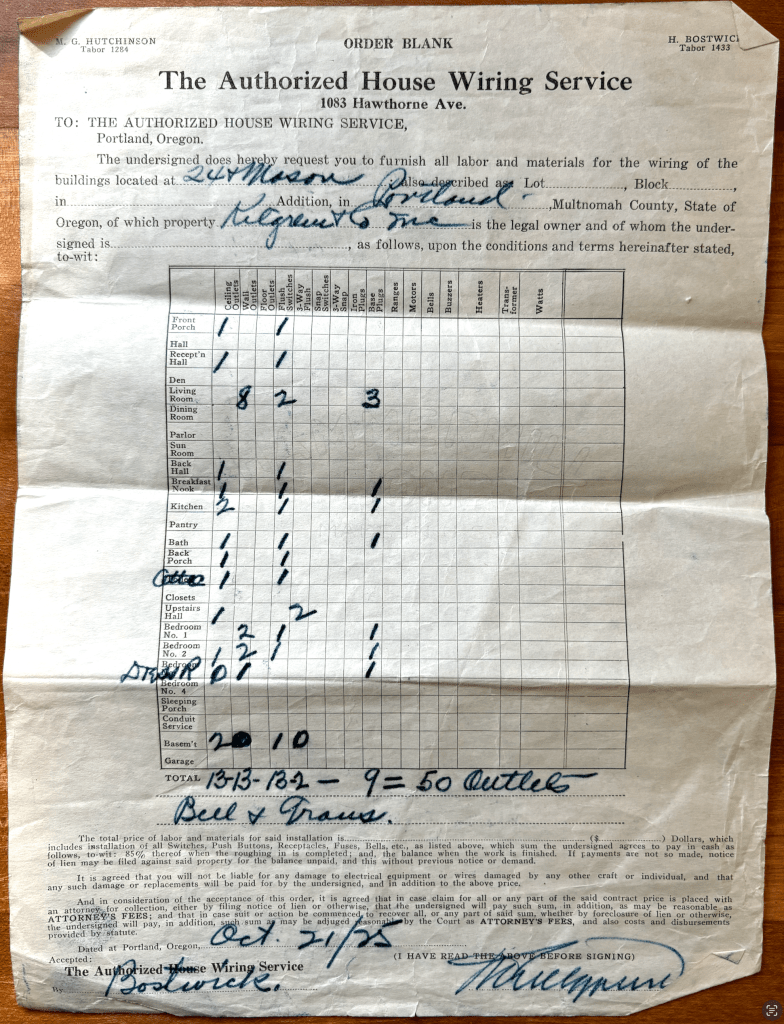

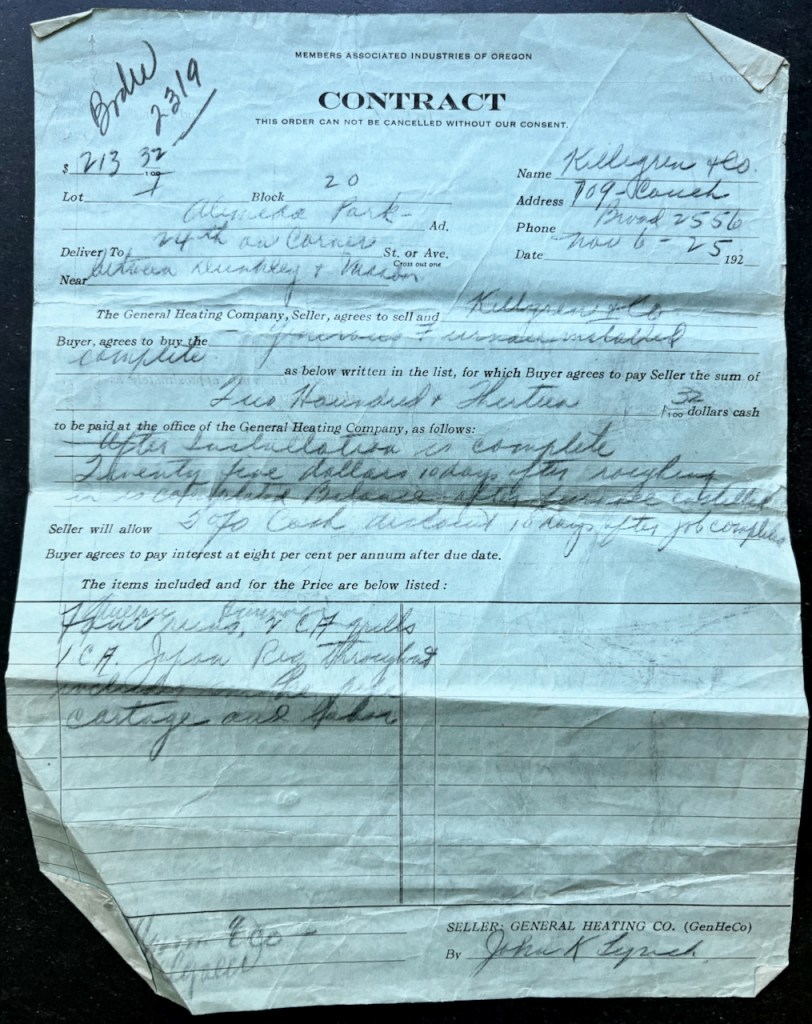

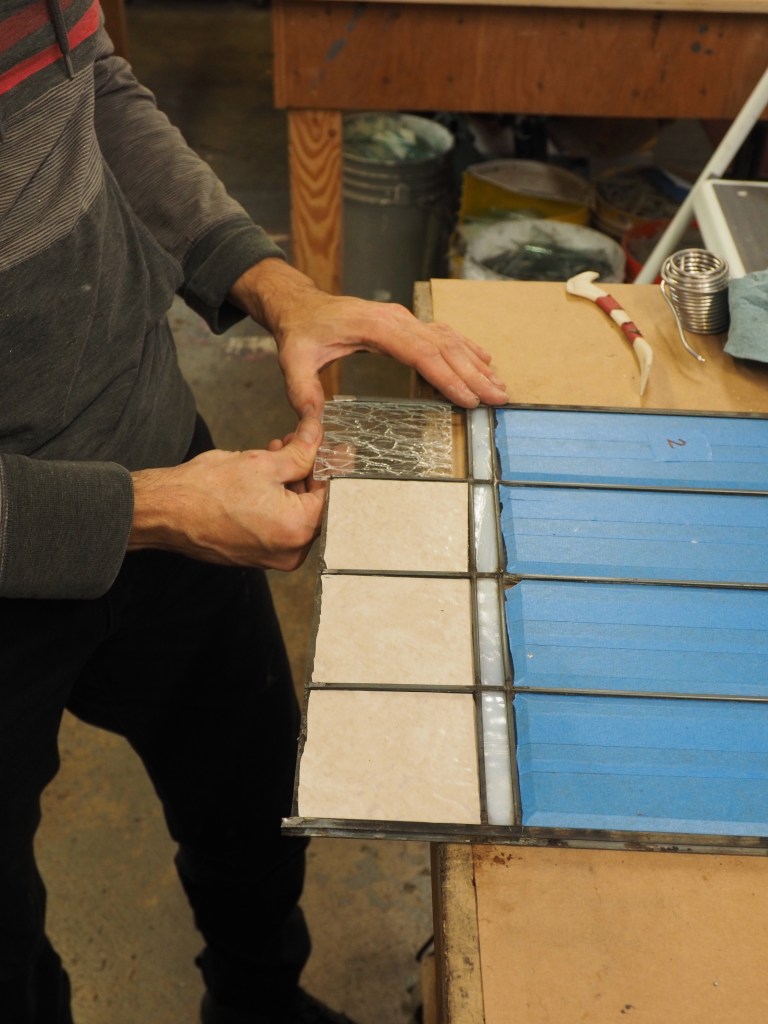

It’s as if the house is brand new: every window (the old ones were salvaged), all the doors, roof, heating (and now air conditioning), electrical, plumbing, floors, all wall surfaces, fireplace (the original mantel and built-in bookshelves are still there). Repaired and waterproofed foundation, new sanitary sewer line, fiber optics. Everything about the kitchen. It’s been a busy place.

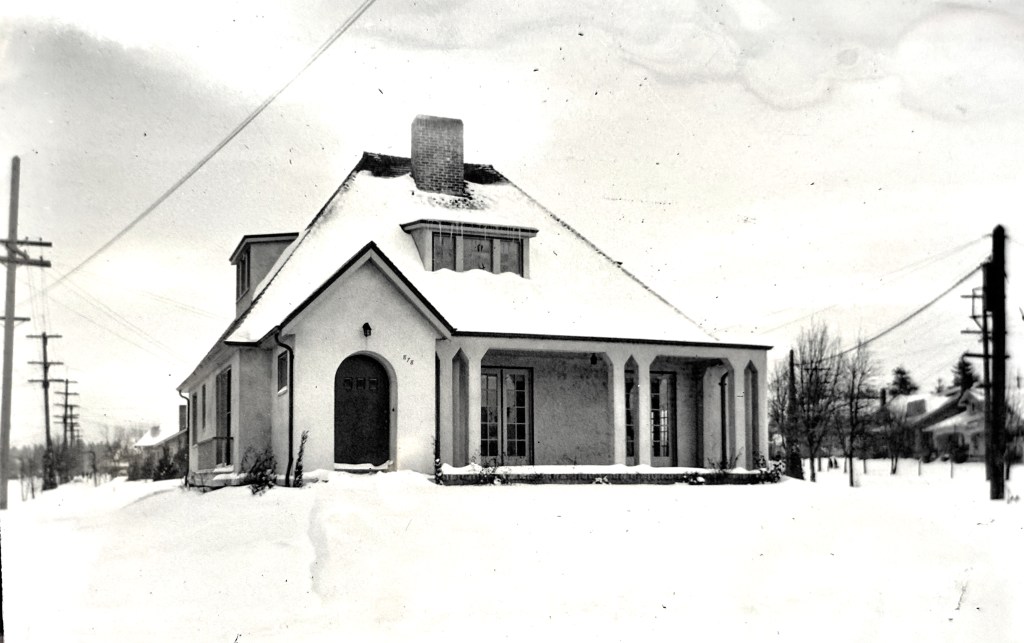

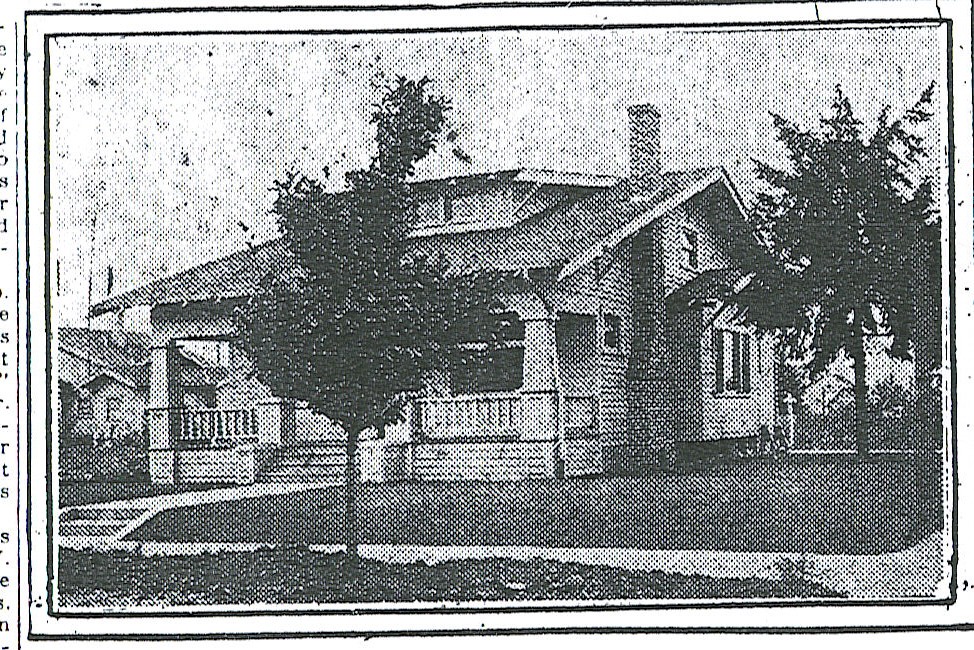

NE 24th and Mason, photographed in December 2024. Note repaired front porch columns at far right.

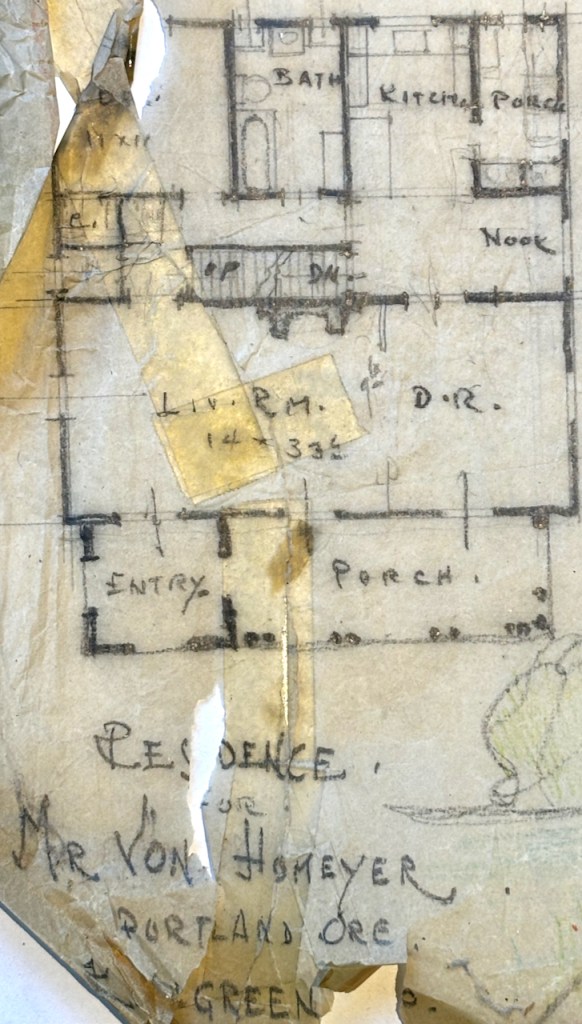

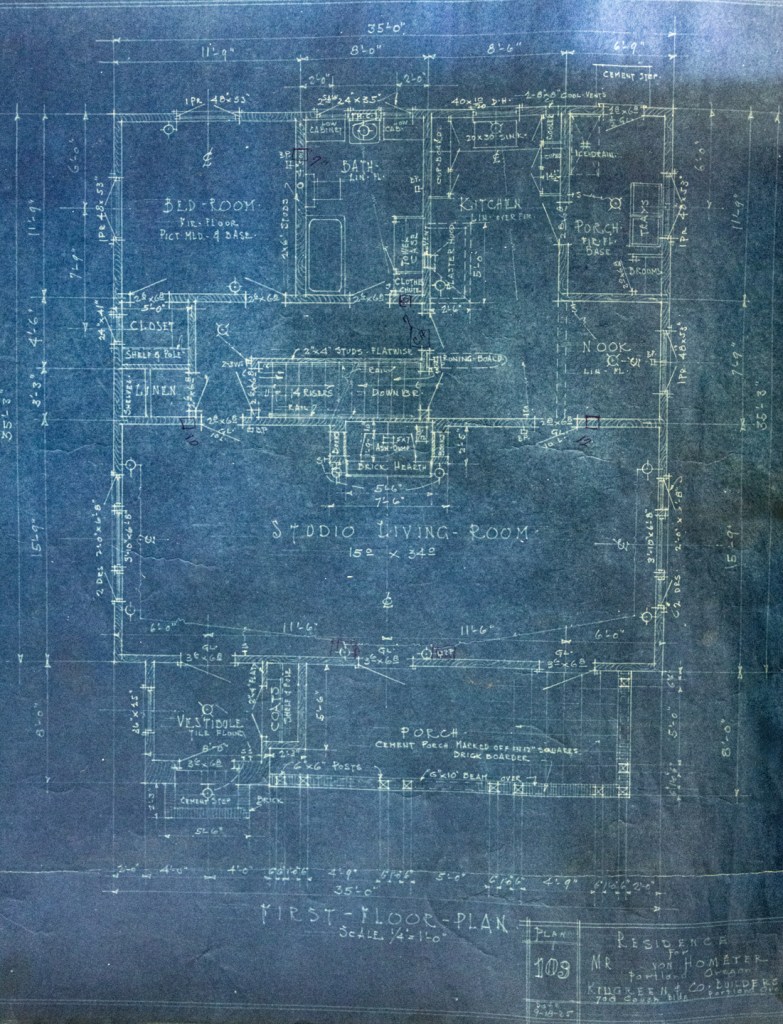

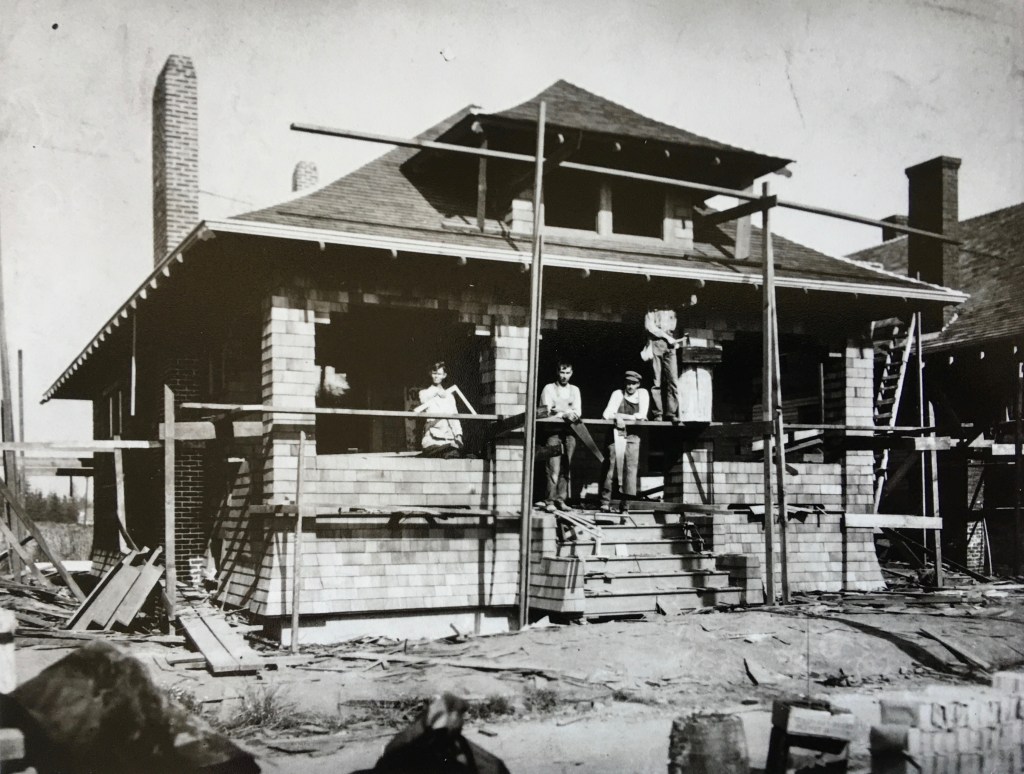

But still, when you see the “then” picture from 1925 when the house was built, and a recent photo from this December, it’s definitely the same time traveler, just transformed for its next 100 years.

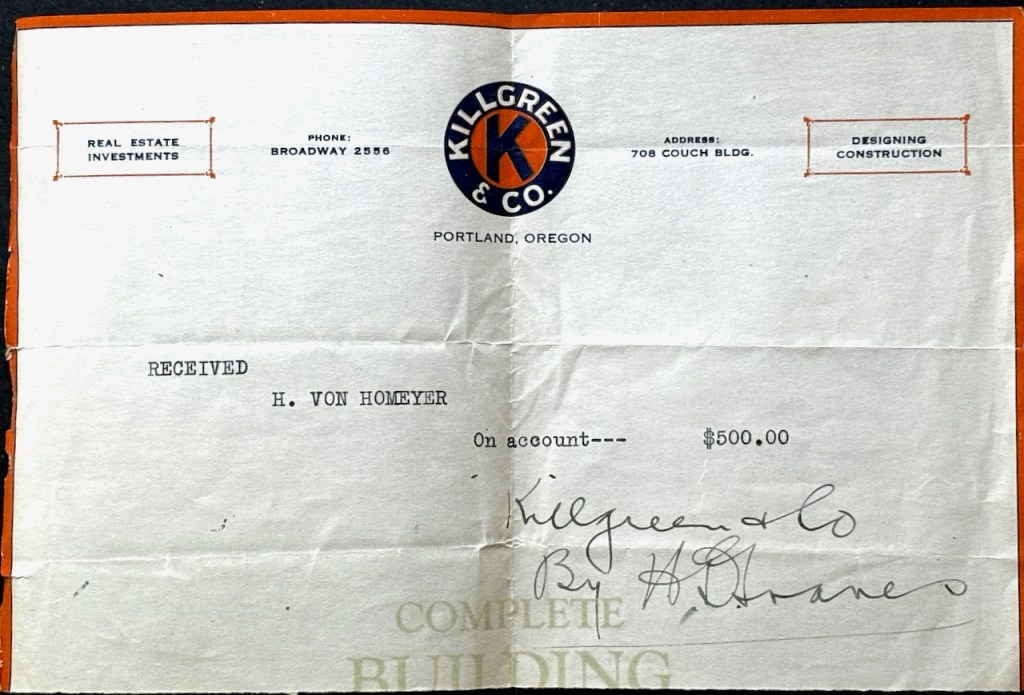

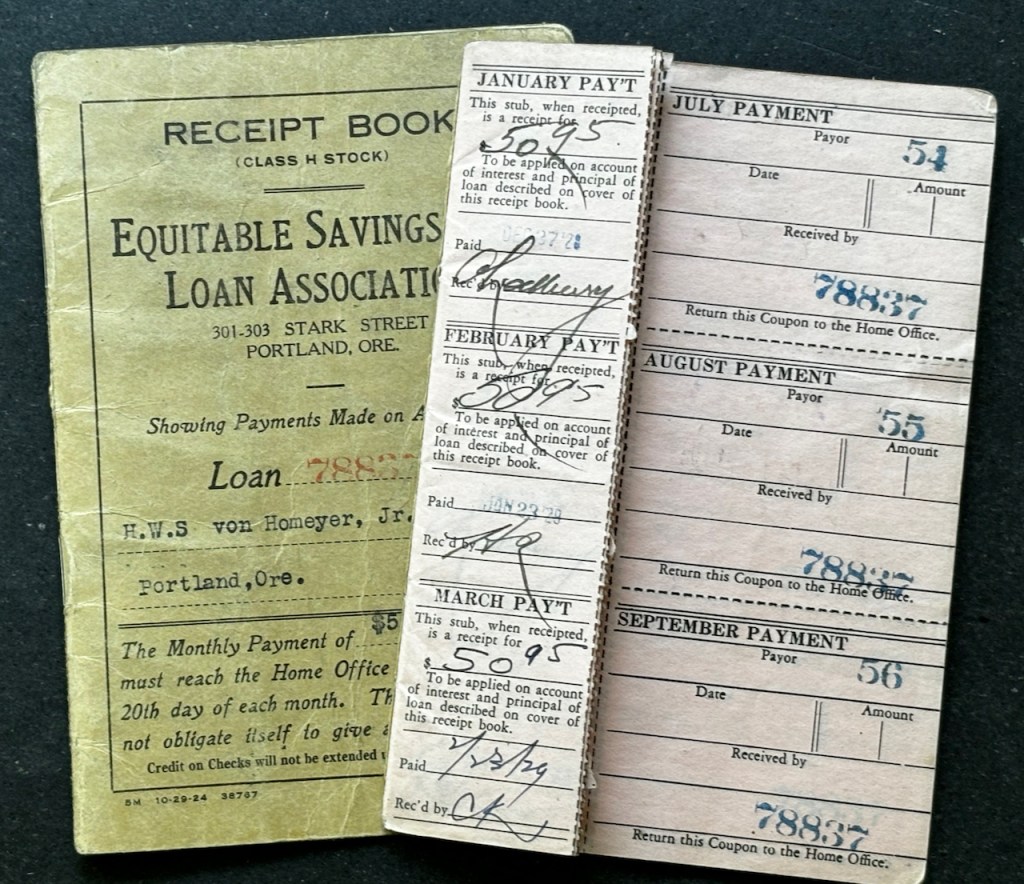

AH readers will recall that neighbors Jaylen and Michael Schmitt bought the house earlier this year after the youngest son of the von Homeyer family, now in his 90s, moved to a care facility. The house had been in the same family for almost 100 years, and the brothers lived there their entire lives.

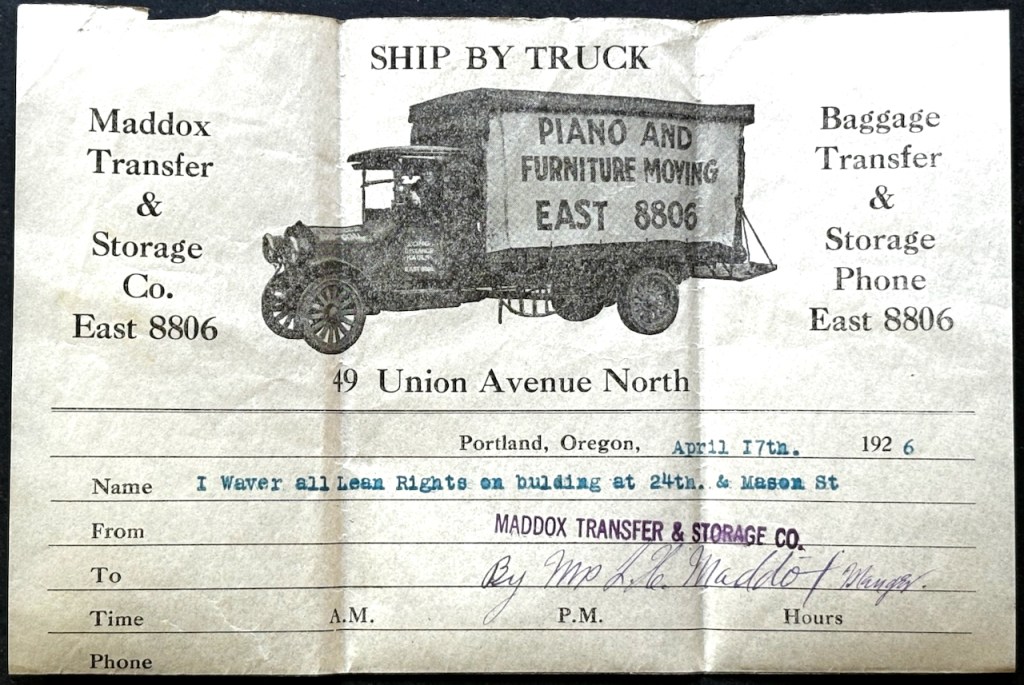

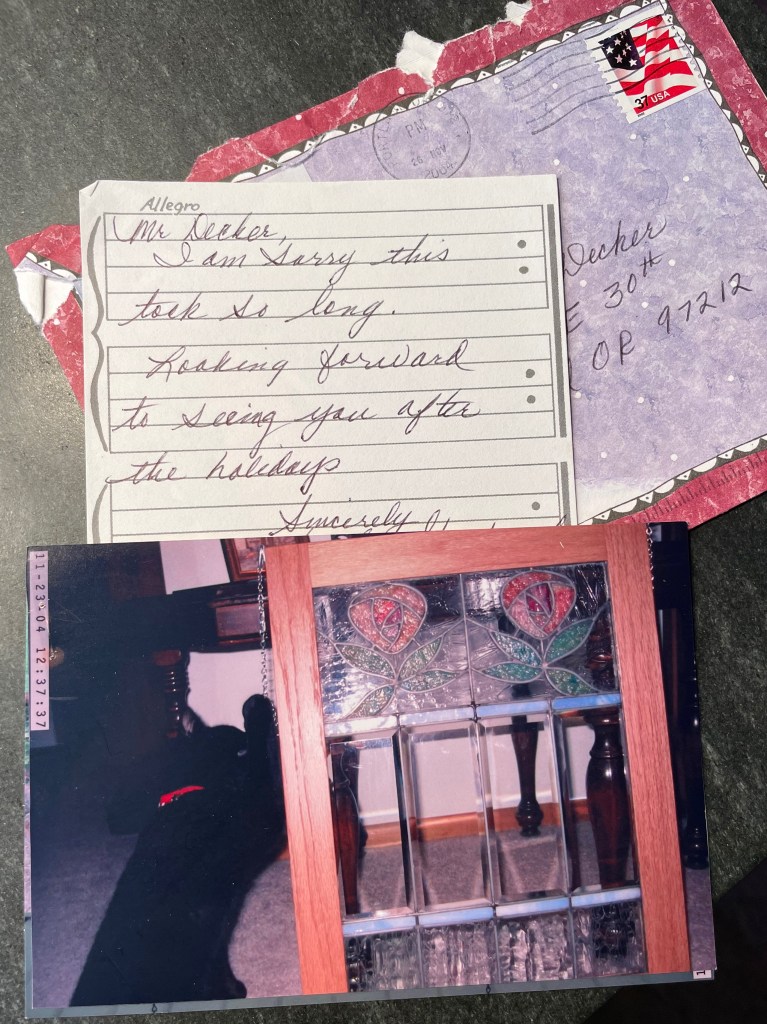

The Schmitts, like many in the neighborhood, were concerned the house would eventually be a tear-down and that something else built there could be an eyesore or worse. When they bought it, the house was jammed to the ceilings with boxes, papers and an incredible collection of items from several lifetimes. They reached out to us for help sorting through a trove of documents and curating some of the items. We re-homed 30 pounds of precious photos to far-flung family.

Four months of thinning and organizing led to a well-attended estate sale in May and gradually as the house was emptied, the Schmitts worked with architect Mary Hogue of MkM Architecture to plan for adapting the house.

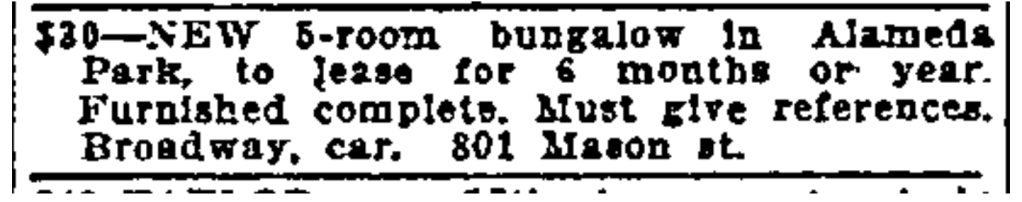

On the first floor, the existing bedroom and bathroom remain (all the plaster throughout the house has been replaced with drywall). The kitchen has been enlarged and will feature an island, two sinks and all the latest appliances. A newly re-opened and restored front porch is accessed by new french doors leading from the living room.

Looking into the living room / dining room. New French doors lead out onto the newly restored front porch. Framing is in, at left, for the fireplace.

The large kitchen features two sinks, will have a central island with cabinets, wall-hung cabinets all around, and a door out into the large backyard.

Upstairs, there are now two full bedrooms, each with its own bathroom, and a giant walk-in closet and dressing area with a huge bank of windows, and a combo washing machine/dryer.

This bedroom upstairs features lots of light and a large closet.

Upstairs, the primary bedroom features large windows and a giant walk-in closet to the left. An en suite bathroom is to the right.

The walk-in closet off the primary bedroom is filled with light.

In the basement: another bedroom and bathroom; a giant family room and entertainment area wired for surround-sound; and a utility room with washer/dryer and sink.

Michael Schmitt, who lives nearby, has been on site almost every single day. Michael is using a builder and subs to do most of the work, and calls himself a “heavily involved owner.” He says he’s become a very good “cleaner-upper.”

“I want to make sure this house is put together as expertly as possible,” Michael explains. So, he has had a parade of tradespeople helping: framers, plumbers, electricians, stucco experts, drywallers, HVAC experts.

It’s been stressful. Michael reckons he hasn’t had a good night’s sleep this year between worrying about what might be the next surprise, and trying to figure out the puzzle of transforming almost every aspect of the house.

“If I were to offer my earlier self some advice based on this year, I’d have to say ‘you’ve got to be 100 percent crazy to do this.’”

While it has been stressful, it’s also been rewarding in so many ways. First, the Schmitts saved the house and property from what surely would have been a much larger building (or buildings). That alone makes it worth all the work. But Michael has enjoyed working with a great team of experienced tradespeople, getting to know his neighbors better and saying hello to the daily stream of passersby, many of whom offer thanks and encouragement.

This week, work on the house is at about the 60-70 percent level. Last week was drywall installation and mudding. Yet to come: painting, trim and finish carpentry, plumbing fixtures, floors, kitchen cabinets (and everything about the kitchen). So many details. And then there is the landscaping, driveway, fencing. Still plenty of work to do.

Michael is hoping the house will be ready to put on the market in the spring. When that time comes, he’ll be ready to cross the finish line and welcome new neighbors. “This will end up being a year and half of my life,” he muses when reflecting on all the stages of the work so far. And while it’s been a journey of ups and downs, all the learning, progress, transformations and new friendships have helped make it worthwhile.

We’ll check back with Michael in the new year.