One of the nice things about a visit to Portland City Archives is the serendipity that comes from hanging around with lots of old documents.

You go in looking for a report related to Willamette River water quality in the early 1900s (which you find), and you bump into a folder of 1914-1915 correspondence from Portland Mayor H. Russell Albee that includes a photo of a mother and daughter, eyes fixed on the horizon, starting out on a big walk from Portland to New York via San Francisco.

For us, serendipity often begins with a photo.

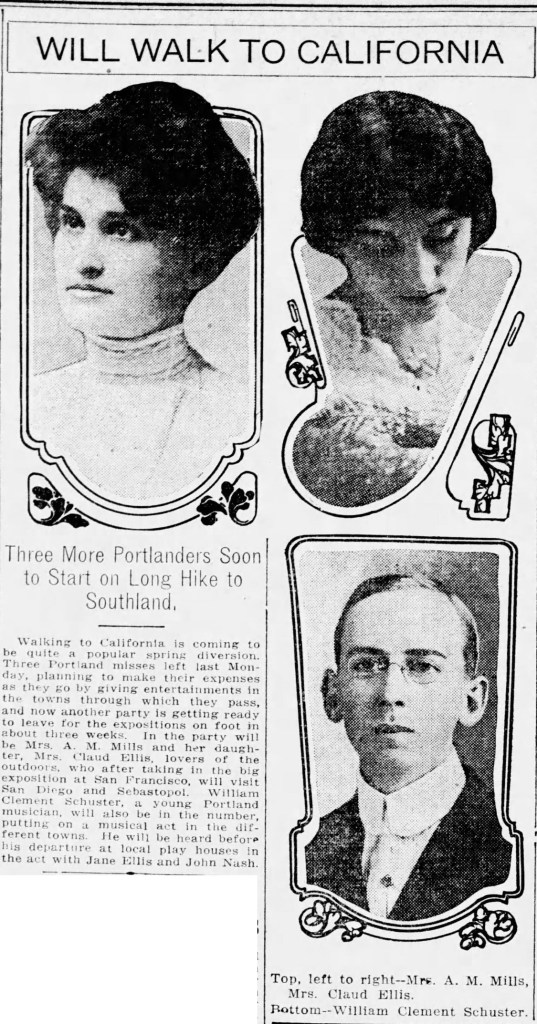

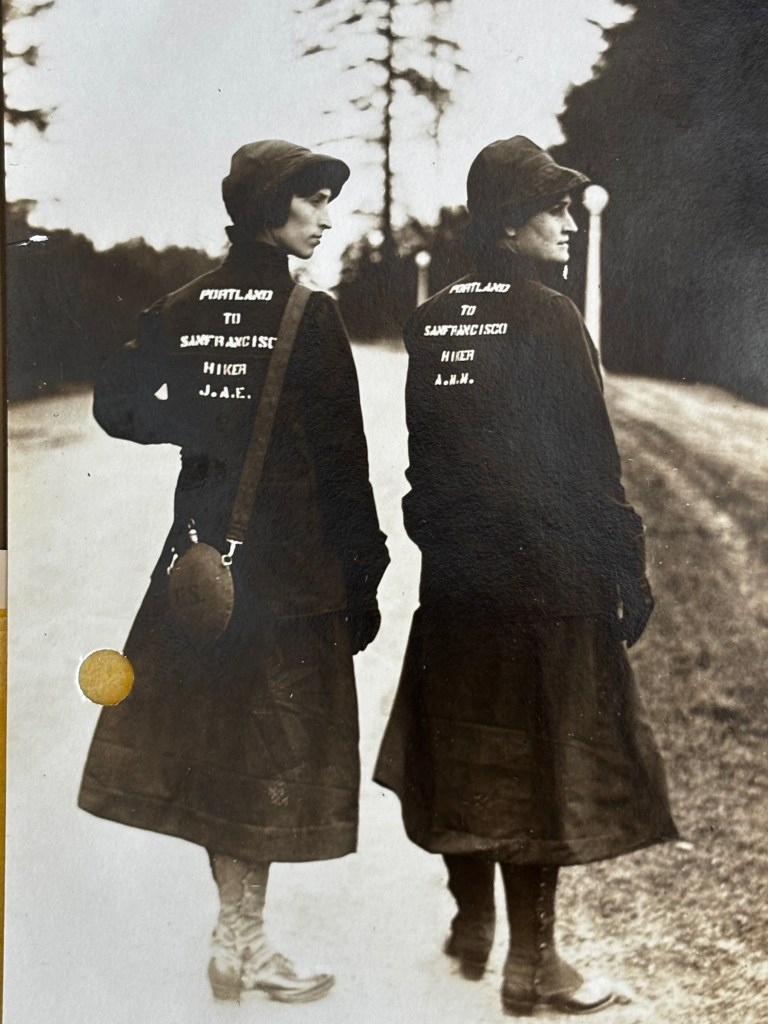

In March 1915, Jane A. Ellis (left, age 25) and her mother Anna Metkser Mills (age 47) prepare to walk from Portland to San Francisco in 40 days. Photo courtesy Portland City Archives, a2000-003.

Walking from Portland to San Francisco and then to New York?

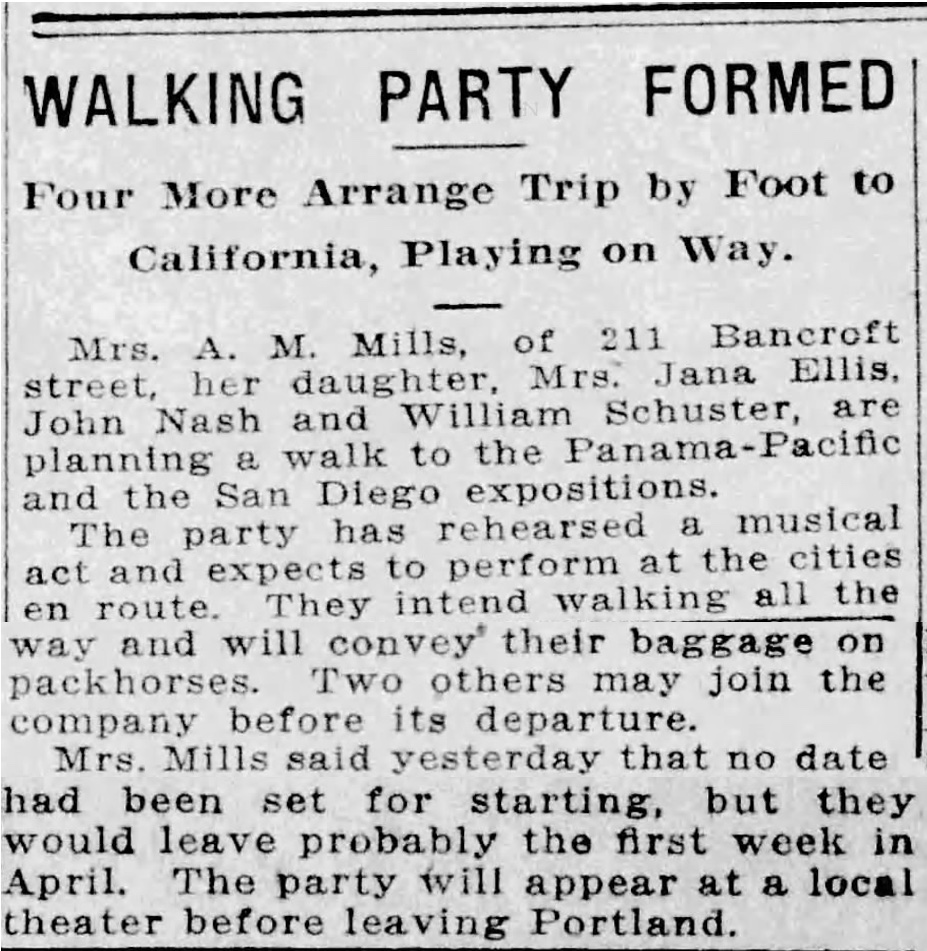

We found carbon copies of eight letters in Mayor Albee’s “Walking Trips” file, all addressed to whom it may concern, as credentials for walkers setting out from Portland in twos and threes, each for different reasons, headed somewhere else: Helena, Montana, Los Angeles, San Diego, Phoenix, New York City. About the same time Jane and Anna set out, three Italian immigrant men left Portland to walk the entire borders of the United States. They too carried a letter from Mayor Albee.

Many of the West Coast walkers were bound for the Panama Pacific International Exposition, San Francisco’s turn at something like the Lewis and Clark Exposition Portland hosted in 1905. Plus, long distance adventure walking was definitely a thing in the middle 19-teens.

As is our custom, we wanted to know more, so we turned to genealogy and the newspapers for insight, where the plot thickened and we got to know this mother-daughter duo a little better. In addition to being walkers and experienced outdoorswomen, they were talented storytellers, musicians and dancers, and as we came to learn, Mother Anna was pretty good with a gun.

First, some basics: Anna Metsker Mills was born in Indiana in 1868 and came west with her husband John. They had three children in Portland: Veta, two years older than Jane, and John, two years younger. In a double tragedy of tuberculosis, Veta died at age 16 and John died at 17. Anna and John’s marriage soon ended, bonding mother and daughter, who both worked for Pacific Telephone and Telegraph Company in Portland.

Here’s a photo we found in a genealogy database of Jane in 1914, the year before the walk, atop the brand new Pacific Telephone and Telegraph Building downtown at SW Park and Oak. She was 24.

Source: Ancestry.com

By the time Jane—who also sometimes went as Jana—joined her mother for their walk in the spring of 1915, she had lost both of her siblings to tuberculosis, seen her parents divorce, been married at age 17, divorced, and had borne two children, one died at birth and the other was seven years old during the spring of the big walk, living with his single father—a real estate broker—in southeast Portland.

You get the picture: these were two resilient people who had known deep loss and sacrifice. You can sense the steel of them from that first photo.

They were smart and planful as well, telling the Oregon Journal on March 22, 1915 they had been planning this journey for two years, and had even taken out a classified ad in the Journal to recruit another member of their party, a musician. All part of their strategy for making ends meet along the way.

Before leaving Portland (they were not the first group of walkers to head south that spring) the newspapers wanted a word. Or maybe these two wanted to make sure the newspapers knew.

Regardless, settle in for a good read and let’s follow along as their stories gain momentum the farther south they go.

From The Oregonian, March 11, 1915

From Oregon Journal, March 14, 1915

From Oregon Journal, March 22, 1915

From Oregon Journal, April 29, 1915

From the Statesman-Journal, May 4, 1915

The Albany Democrat Herald noted when the pair passed through there on May 8th “They left Portland without a cent and are making their expenses by appearing in theaters, etc. along the way.”

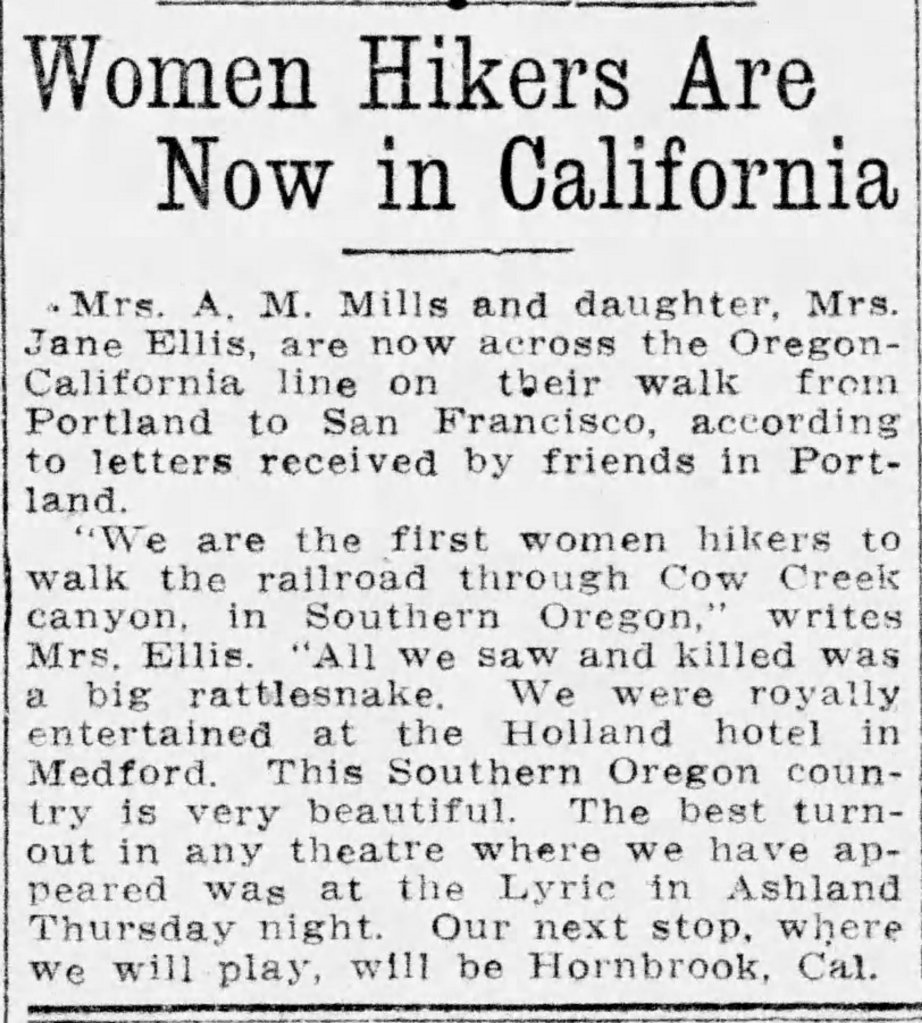

As they neared Douglas County, the Roseburg News-Review tracked their movements: on May 20th musician John Nash and singer Katherine Vernon joined them in Oakland, Oregon north of Roseburg. May 28th they were in Grants Pass. June 1st they passed through Medford, and the paper reported they were navigating by following the telephone lines, hauling their baggage on horseback, and staying in telephone offices whenever they stopped. They seemed to pause for a while in Ashland, giving multiple well-attended performances at the Lyric Theatre.

From Oregon Journal, June 5, 1915

From the Orland, California Register, June 23, 1915

At last, on July 11th, the group—now down to three—arrived in San Francisco. Their stories and a photo—and a sidebar about selling newspapers on the street—appeared on page 4 of the July 12, 1915 San Francisco Bulletin. Click on this for a good read (and look for the Smith & Wesson).

But that’s the last we hear of them, nothing further about going on to San Diego or New York, or any points in between. We’ve had a good look around at newspapers along that way, and there’s nothing. We have to rely on genealogy to give us hints about how their stories end.

They both return to Portland, where daughter Jane marries in 1919, 1923 and 1930, regains custody of her son Wilbur and sets up house with new husband Oscar Severson on SE 17th Avenue, where we find her in the 1930 census working as a debt collector. Living in the house with them is mother Anna, who later dies at home on August 19, 1935 at age 67, and is buried at Lone Fir Cemetery.

In the early 1950s, Jane and Oscar leave Portland to live near her adult son in Los Angeles. One photo of her from those years convey Jane’s character, showing her in red dress and pearls in some snowy pass. Was she retracing the walk?

Source: Ancestry.com

Oscar dies in January 1955 and Jane lives on in Van Nuys until July 6, 1967 when she dies at age 76. Death notices and obituaries don’t remark on the big walk of 1915. But now we know, thanks to a serendipitous morning in the archives, a letter from Mayor Albee, and a photograph of mother and daughter peering into the future.