It’s always been a visual landmark on NE Wistaria Drive: the 1928 turreted English Tudor style house that anchors the big downhill bend at the confluence of Wistaria, NE 41st and Cedar Chavez Boulevard. The tower with its tip-top weather vane, 360-degree windows and tent-like roof dormers. The prominent gable ends and half-timbering. The brick, decorated entry way.

They don’t build them like this anymore.

For more than 30 years, we’ve walked by and felt the cry for help from the house and its former owner—who passed away in August—as the weeds took over, the windows cracked, the porch sagged and garbage piled up.

Neighbors are paying extra attention this week because the Wistaria turret house is now for sale. Many are hoping for a capable, patient, history-focused buyer who can bring it back to life.

We walked through this week to take a measure of how much work there is to be done. It is a major fixer-upper. All the building systems will need to be replaced and upgraded: electrical, plumbing, heating and ventilation; new kitchen, new roof. Every surface, finish, floor and window needs TLC. The foundation needs attention too, perched as it is on the slope of the ridge. Don’t forget the landscaping.

While the amount of work to be done is staggering, so is the grace and beauty of the original construction and the uniqueness of so many of the home’s interior spaces. There’s nothing else quite like the top turret room.

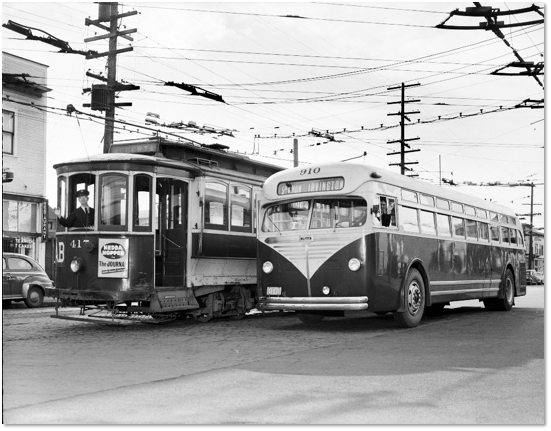

Check out this view of the house from April 1935, showing original owner Anna Hummel watering the garden (photo courtesy Portland City Archives AP/25295) and today.

3880 NE Wistaria Drive is listed by Cee Webster with Neighbors Realty. Cee has a deep appreciation for the character of the house and the reality of the work at hand, and has shared photos which you can find here. Cee will be accepting offers until December 8th at 9:00 a.m

In some ways, the complexity of the house mirrors the story of its earliest years. Built in 1928 by Jens Olsen for German immigrant Carl Hummel and his American wife Anna, the house embodies design aspects from Carl’s growing up years in Reutlingen, Germany.

Carl was a tailor. He and Anna arrived in Portland from Quincy, Illinois in 1907, and operated a tailoring, cleaning and dye business at NE 22nd and Sandy.

In the mid 1930s when trouble was brewing in Germany, Carl, then in his 60s, wanted to be back in his homeland. Working through an intermediary here in Portland, Carl arranged an exchange of homes and businesses with a Jewish German family who were trying to flee to the U.S. but had been blocked by the German government. Correspondence, telegrams and other documents archived by the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum convey the complexity of the exchange.

The situation for the fleeing German family was becoming dire; time was running out. The back-and-forth correspondence is steeped with anxiety and barely-contained impatience, but also with respect. If the families could organize a trade, neither would need to send money across international borders, which was forbidden.

Finally, in November 1936 with an agreement in place and papers approved, Carl and Anna moved home to Germany. Not long afterward, the very relieved Lowen family from Görlitz arrived in Portland as the new homeowners of the turret house on Wistaria. They became naturalized citizens and lived in the house for more than 30 years.

We’ll explore this story—and the unfolding next chapter of the turret house—in future posts.