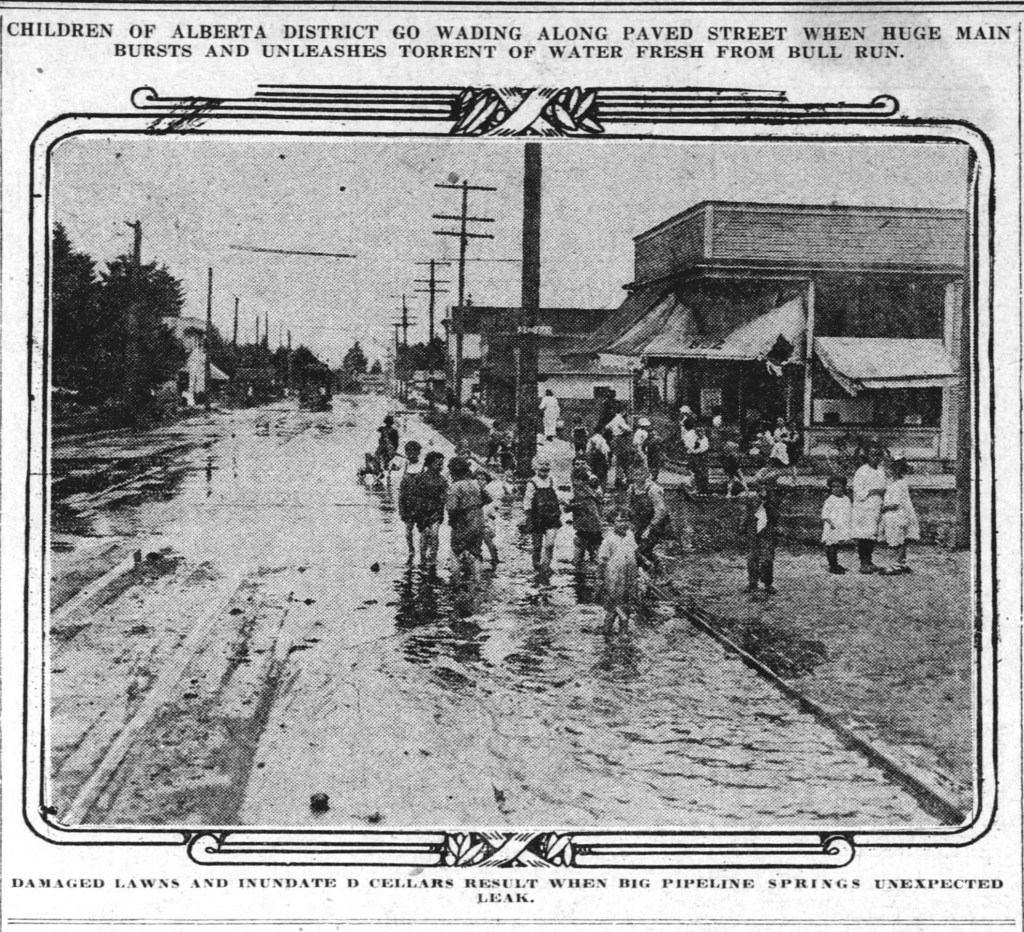

Rose City Herald front page, August 29, 1930

The Rose City Herald was a weekly broadsheet newspaper published from 1922-1944 covering the middle neighborhoods of Northeast Portland: Rose City Park, Gregory Heights, Irvington, Alameda, Beaumont, Wilshire, Sullivan’s Gulch and Kerns. That far back, the name “Hollywood” had not yet been coined: that would have to wait for opening of the Hollywood Theater in 1926, when the surrounding neighborhood took on the name of the iconic Sandy Boulevard theater.

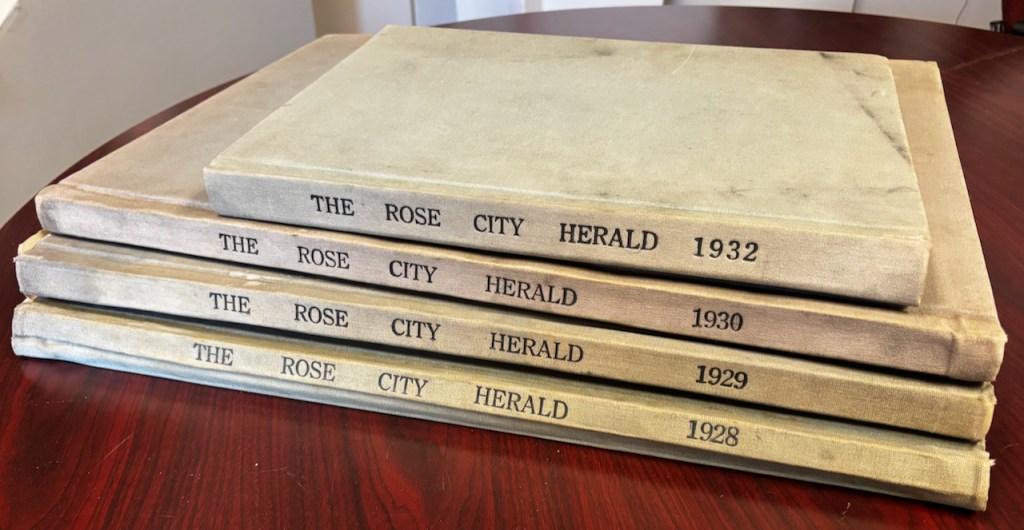

This winter, I’ve had the privilege of perusing more than 200 editions of the Herald, which were bound into four large books from 1928-1929-1930-1932. For almost 100 years, the books have been in the careful stewardship of Hollywood business leaders; the last 50 years in the library of Paul Clark, informally known as the “mayor of Hollywood.”

Paul Clark is a one-man institution of memory and business in Hollywood who knows every inch of the place and its history. A founding member of the Hollywood Boosters and a deeply community-spirited person, Paul has held onto the four books for decades, since they were passed along to him by elders in the business community when he was just starting out.

Last summer, informal conversations with Paul and Todd Milbourn, publisher of the Star News, led to my introduction to the Rose City Herald, which quickly turned to fascination as I spent hours in Paul’s Hollywood office poring through back copies.

Paul Clark examines one of the big books in his Hollywood office.

As a researcher who has closely followed many aspects of neighborhood development in the early 20th century through the pages of The Oregonian (Portland’s morning paper) and the Oregon Daily Journal (our afternoon paper), the Herald’s fresh, hyper-local look at neighborhood life brings so many new insights and surprises. Take, for instance, the rumored, planned (but never executed) construction of a Hollywood Theater counterpart in the Beaumont neighborhood near NE 42nd and Fremont. Who knew?

Having another frame of reference through which to view neighborhood history is priceless, especially when that frame is as local as the Rose City Herald, which was based in the Herald Building, 1820 NE 40th Avenue, home of today’s Hollywood Community for Positive Aging. Purpose-built in 1929 to hold the newspaper, its presses, a post office and a small grocery, the building retains its original name set in terracotta tile on the front facade.

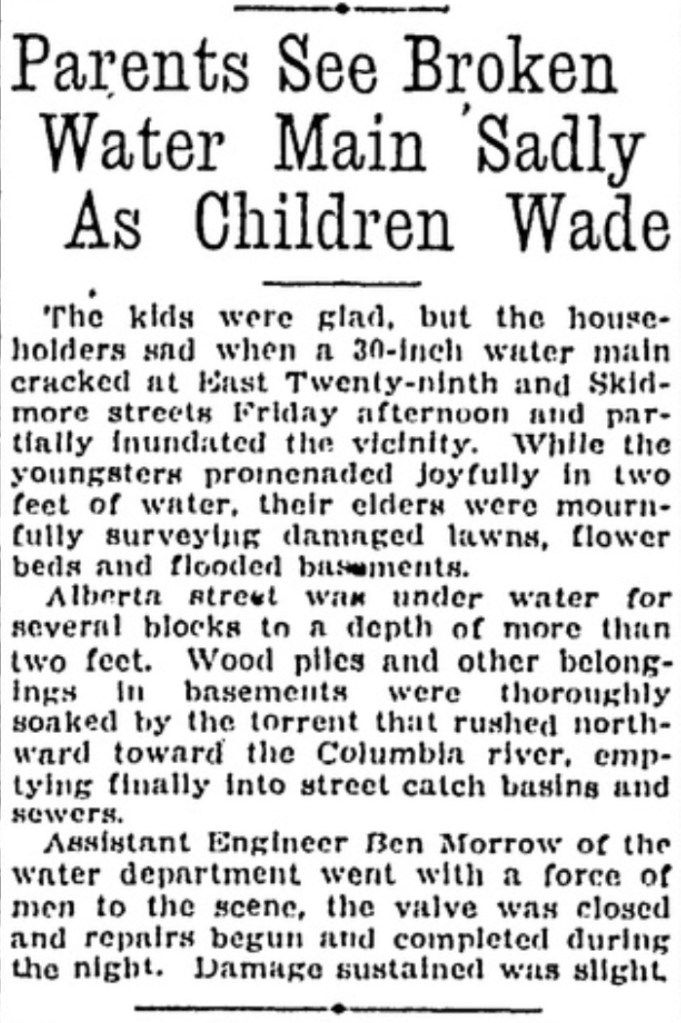

Soaking up the stories

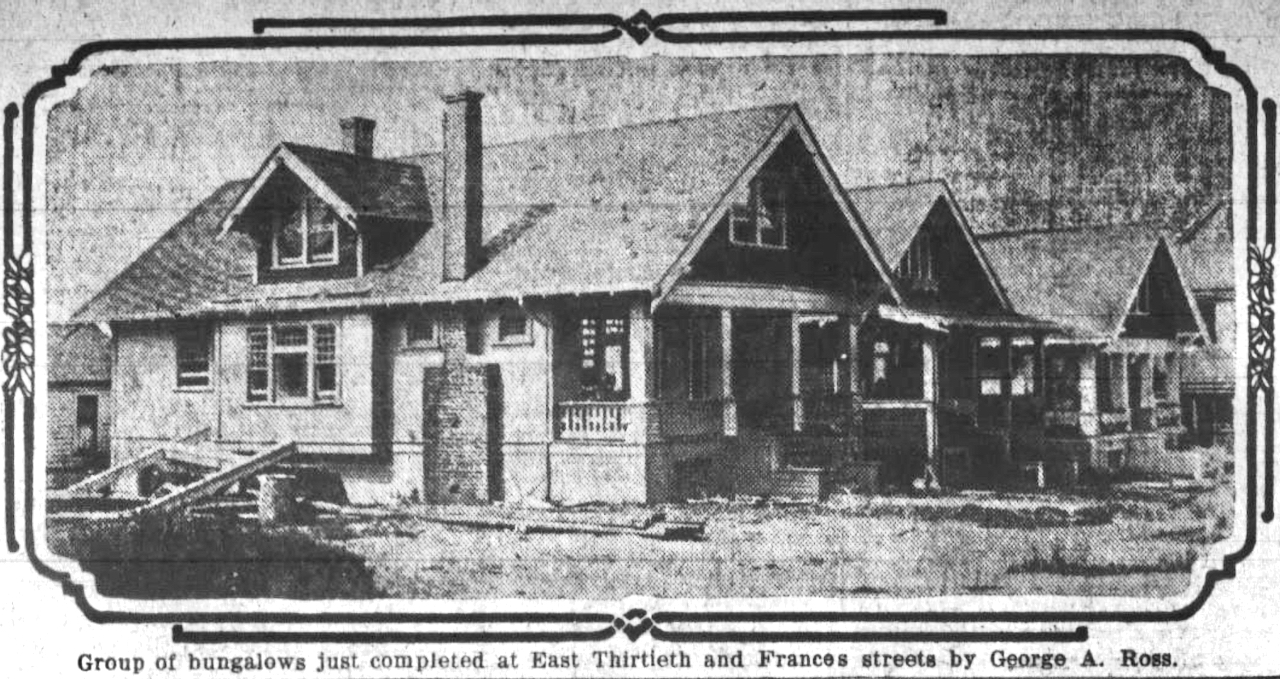

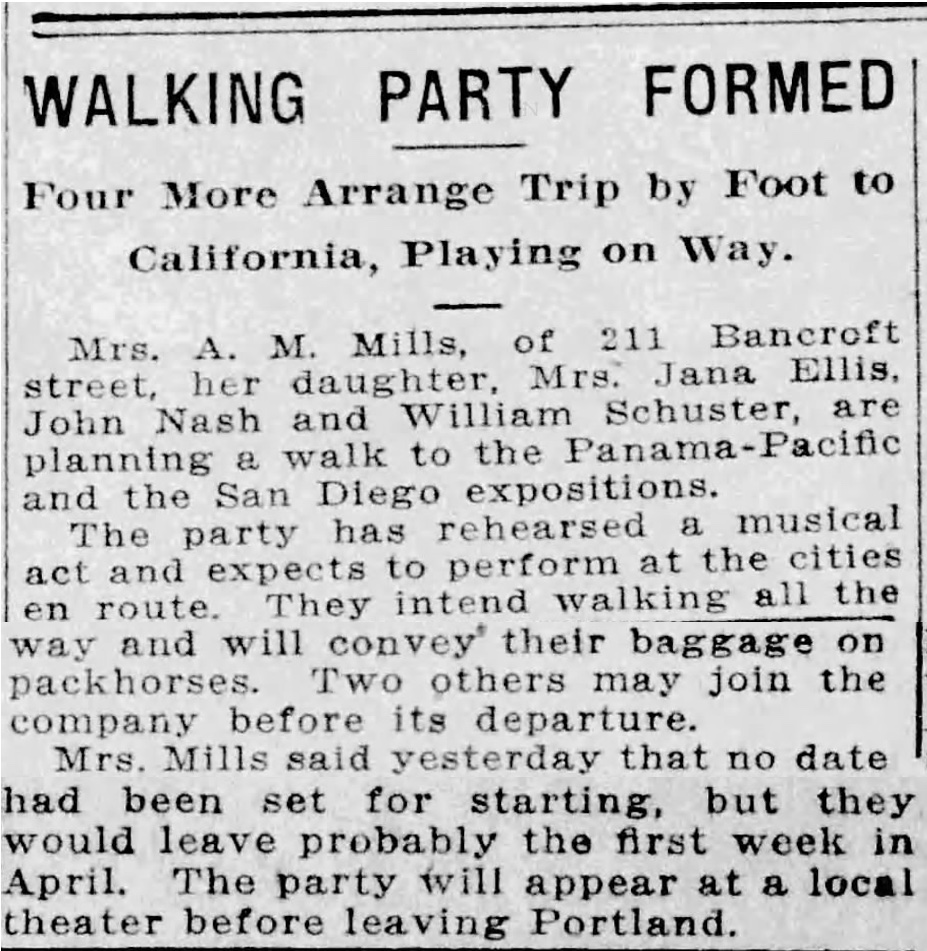

A typical edition of the Herald provides a weekly accounting of hundreds of moving parts from civic life: school news and plays, kid sports, fraternal, sororal and scout group gatherings, police calls, homebuilding and real estate development, births and deaths, bridge clubs, family reunions, business activity, health needs, traffic problems, recollections of an even earlier history and memories. Sandwiched in between are advertisements from local shoe shops, grocers, plumbers, builders, banks, and much more.

Consider:

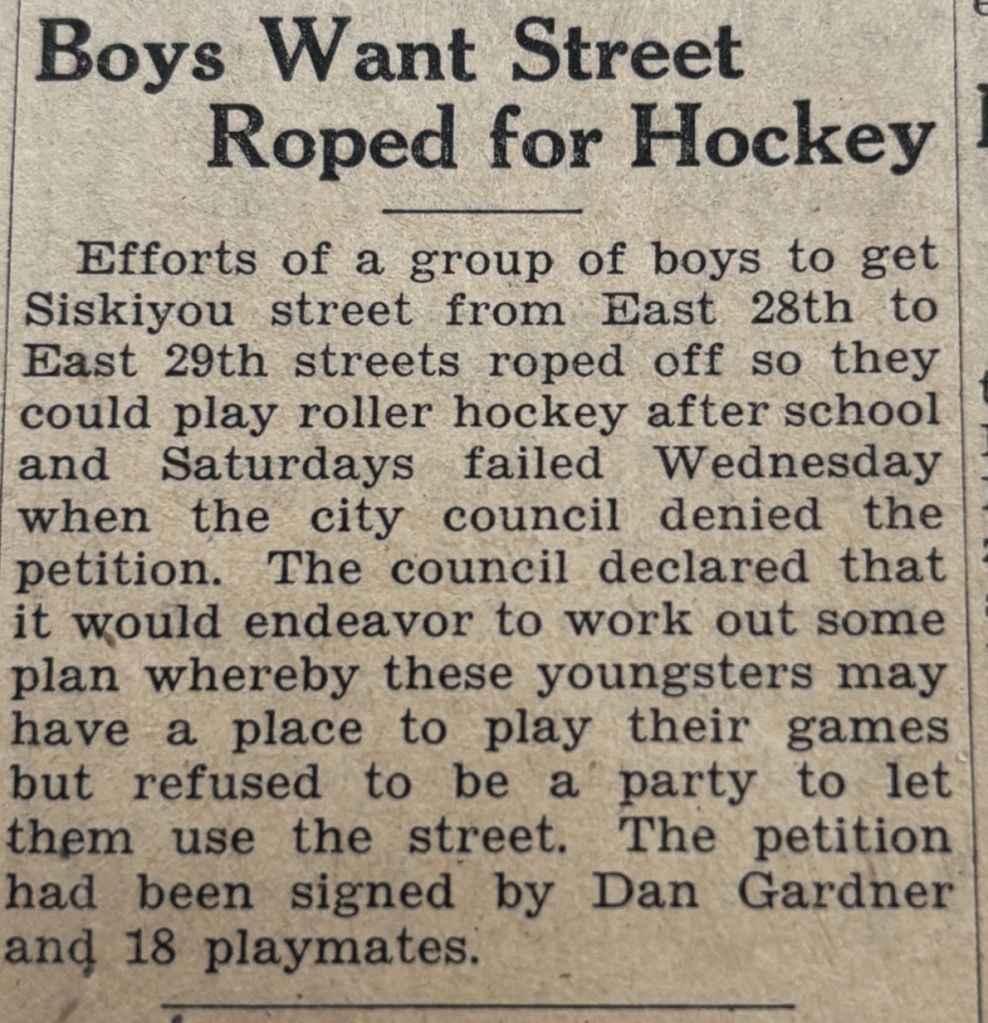

The story of the 18 kids who played street hockey on NE Siskiyou petitioning city council for permission to rope off the street for safety (permission denied).

From the Rose City Herald, February 27, 1930

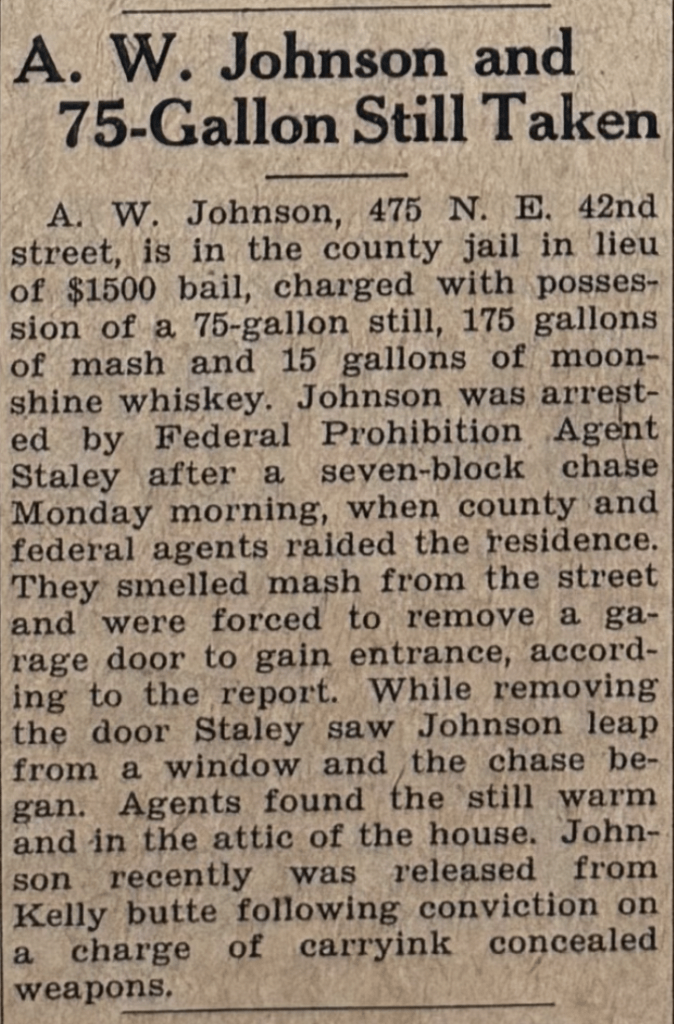

A moonshiner operating on NE 42nd Street led a federal prohibition agent on a seven-block chase through the neighborhood leading to arrest and confiscation of a still, mash (an oatmeal-like mixture of grains used in the fermenting process) and 15 gallons of moonshine. The Herald covered lots of stories about local moonshiner-lawbreakers operating throughout Northeast neighborhoods.

From the Rose City Herald, June 27, 1930

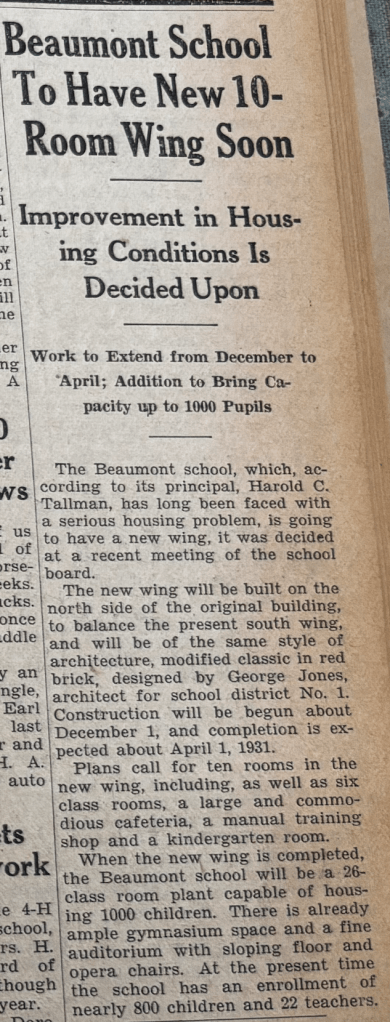

In the fall of 1930, Beaumont School families were thrilled to learn about a new 10-room north wing addition planned for opening in April 1931 that would add six class rooms, “a large and commodious cafeteria, a manual training shop and a kindergarten room.” Everyone was hoping the new wing would take the pressure off the school, which in its smaller, original version had 800 students and 22 teachers.

From the Rose City Herald, October 3, 1930

One of the beauties of a local weekly newspaper is its ability to capture and slow down a community’s incremental stream of life long enough for reflection. There is sadness and loss, lots of change (these were mostly brand-new and growing neighborhoods a century ago), and plenty of joy, often reflected in how the community came together in schools, living rooms, churches and playgrounds.

If newspapers are the first draft of history, then these Herald books contain the ingredients that explain how these neighborhoods got started. The tens of thousands of news items reveal a familiar landscape we all know – our homes, schools, and neighborhoods – and a pattern of living that is both strikingly different yet similar.

This winter as I spent more time with these Herald stories, it occurred to me how valuable it would be to share them with the wider community and future researchers.

Preserving and sharing the Herald

Fortunately, there is a means to do this through the Oregon Digital Newspaper Program based at the University of Oregon, whose holdings you can find at the website Historic Oregon Newspapers. This online, searchable collection includes 420 newspapers from across the state, going back to 1848.

As a researcher, I use this collection all the time and can attest to its value in helping turn back the clock to learn more about a place, a person, event or topic. Want to know who built that building? Want to know about school enrollment trends? How about events that have happened at your address? It’s all here. Plus: it’s fascinating reading.

Recently, I had a chance to visit with Elizabeth Peterson, director of the Oregon Digital Newspaper Program, about the existence of four years of the Herald. She was thrilled: “The copies you have are likely the only ones that exist so the urgency to preserve them is strong.”

While The Oregonian and the Oregon Journal were the statewide daily papers of record for many years, Peterson credits local newspapers like the Herald with offering a special lens to reflect the life of a community, the formation of its social and actual infrastructure. Being able to have a localized view — often a different perspective on similar topics covered in the papers of record — helps round out our understanding of the big picture.

“Local papers present a lively, diverse and interesting set of stories that help us understand our communities,” Peterson said. “They celebrate small things that are often delightful, and that aren’t covered in the big dailies.”

So last month, with the blessing of Paul Clark and the encouragement and help of Todd Milbourn at Star News, I signed an agreement with the Oregon Digital Newspaper Program to help shepherd the four big books through digital scanning, indexing, website sharing, and preservation of the actual newsprint. The process will take about a year, with the searchable paper posted to the Historic Oregon Newspapers site by July 2027. It’ll be a resource everybody in Oregon and beyond will be able to explore and use.

Preservation process for the Herald generously funded – Thank you donors

Generous support from a handful of donors has now fully funded preservation of the Rose City Herald, and led to thinking about the next chapter, which could include a similar approach to scanning and preserving two of the papers that followed in the footsteps of the Herald: the Hollywood News (1944-1983) and the Hollywood Star (1984-1994). Back copies of both papers exist and are in safekeeping.

Today’s Star News—published by Todd Milbourn and Lisa Heyamoto—is the current descendant of these other local newspapers. Todd and Lisa are generous donors to the Herald preservation project, plus great believers in and practitioners of community journalism. I feel fortunate to be writing a local history column for Star News.

Maybe 100 years from now, someone will look back—just as we have—and wonder about a century of neighborhood life. Fortunately for them, community newspapers like the Herald, the News and the Star will offer some tantalizing clues.

Next up: Meet Robert and Victoria Case, founders of the Rose City Herald: a brother and sister who grew up in the neighborhood, graduated from the University of Oregon School of Journalism, and went on to careers in writing and news.