Local service and social club has been doing good works quietly for almost 100 years

When you think about Alameda neighborhood institutions and landmarks, a few standouts come to mind: the school, the churches, the ridge, Deadman’s Hill, our particular grid of streets, the big ponderosa pine at Fremont and 29th. We all have our list.

Chances are, though, that you don’t think about—or maybe even know about—one of the longest-lived, active and engaged institutions our neighborhood has known: the Alameda Tuesday Club.

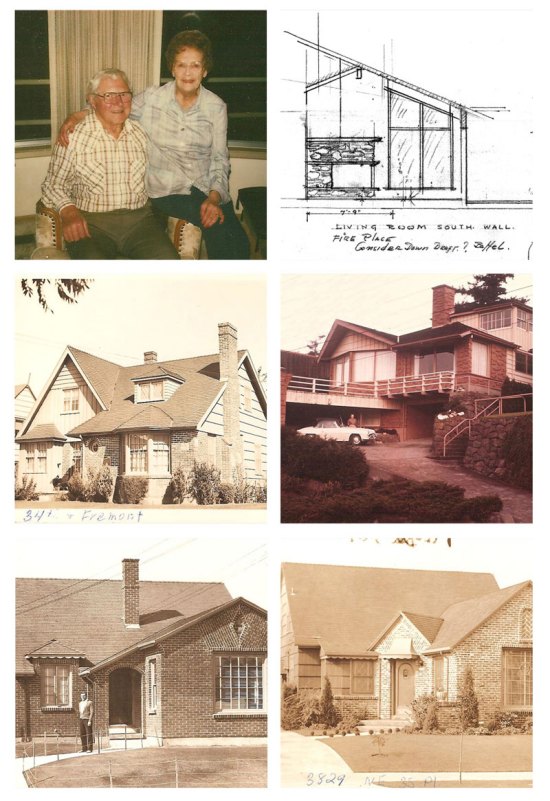

Members of the Alameda Tuesday Club gather in a local home in December 1963. Scrapbooks showing club activities are now in the collection at the Oregon Historical Society. Photo courtesy of the Metschan Family

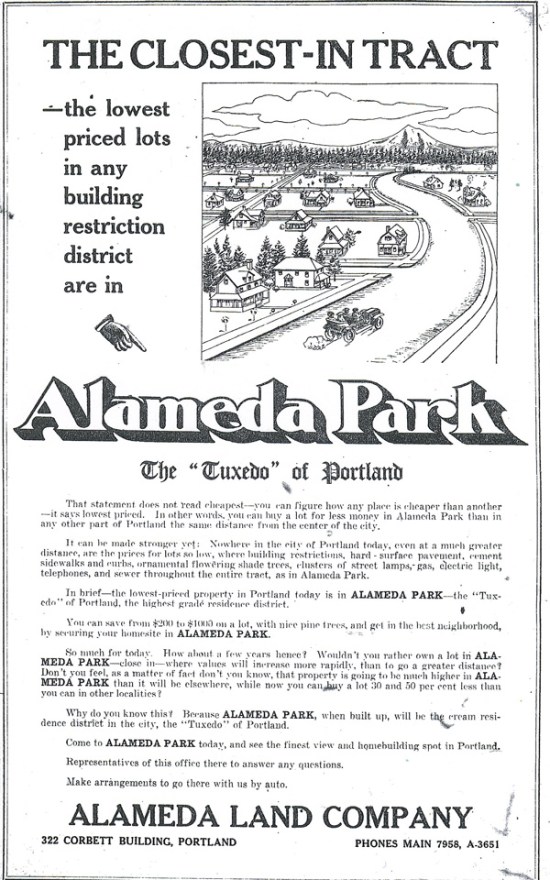

The ATC, as it is fondly referred to by its 36 members, is a social club with a service mission; a collection of active women from the Alameda neighborhood who are quietly carrying on a tradition that began at the dawn of the neighborhood itself. Since 1913, when the first homes were being built in the fields that are now our neighborhood, members of the club have been gathering on a regular basis in a different Alameda home each month for conversation, for learning, for tea and a meal, and to plan good works both close to home and far away.

In 1914, when a down-on-their-luck family was living rough in the 33rd Street Woods (a much wilder version of today’s Wilshire Park) and the Dad had tuberculosis, the club stepped in to provide food, coal, clothing and milk for the children.

When a well-known national suffragette came to town to advocate for a woman’s right to vote, the club boldly hosted an event with her as lead speaker.

When World War I soldiers from Portland were in the trenches in France, the ATC made and shipped bandages and other supplies overseas.

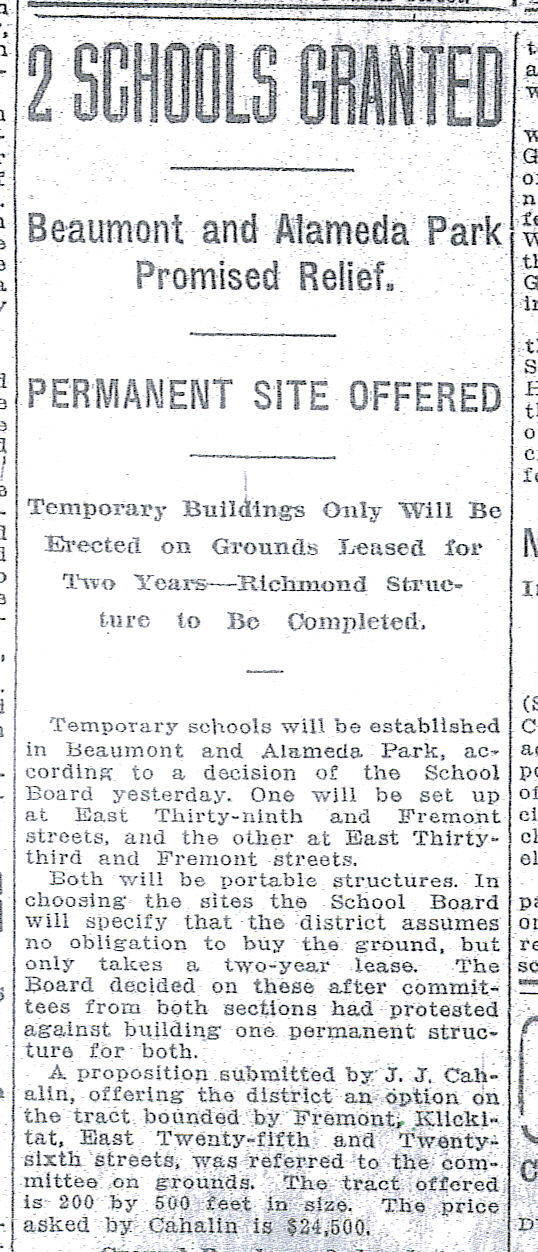

When the young neighborhood clearly needed a school, the Alameda Tuesday Club stepped up to help make the case.

You get the idea: These women are strong and know how to get things done. The list of charitable works over the years is long and generous. But they know how to have fun too: picnics, tea parties, an award-winning flower-bedecked float for the 1916 Rose Festival parade, fundraisers, costume parties.

These days, the club isn’t advocating for schools or building parade floats. But it does make generous gifts to charities, including most recently the West Women’s Shelter, Beaumont School Library, the Jefferson Dancers, the Oregon Food Bank, Friends of Children and SMART.

“When I first heard about the club, I thought it was such an anachronism,” says current president Kathie Rooney, who has been a member since 1986. “But when you are involved in charitable works and you get to know these women, the club takes on a whole different dimension. There is definitely an old fashioned social interaction. But we’re also talking about the issues of the day.”

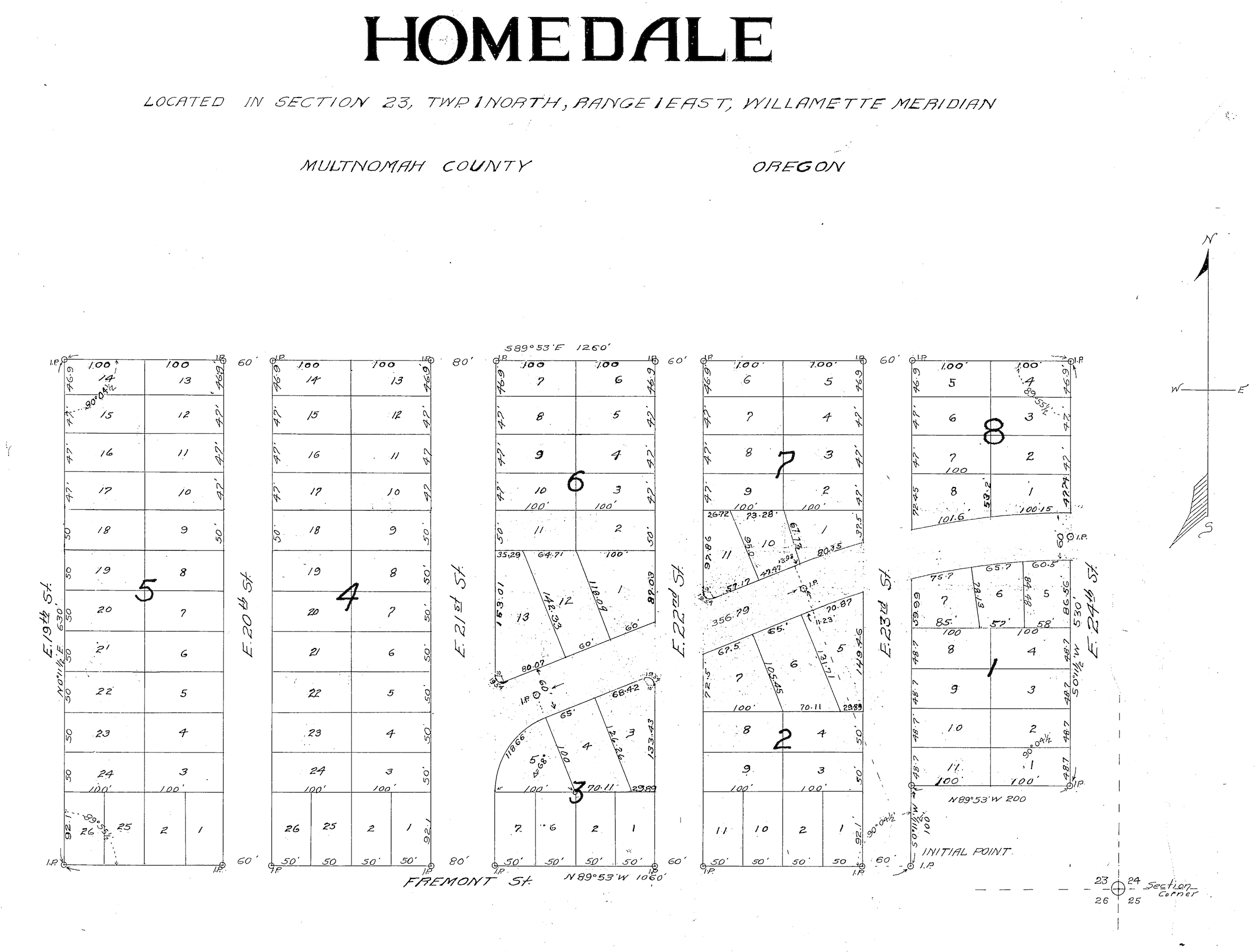

Rooney explains that club bylaws have changed little since 1913, and still require members to live within the perimeter of the original Alameda Park Addition: from Fremont to Prescott and between NE 21st and NE 33rd. Membership in the club is by invitation only—as it has been from the beginning—and no more than 36 members are allowed. Monthly meetings rotate around the club, with a member hosting a lunch in her home on the second Tuesday of the month, nine months of the year. Some neighborhood homes have held multiple generations of ATC members and meetings.

And then there is the unwritten silver tea set rule: tradition has it that a silver tea set must be at every gathering of the club. Look back through the club scrapbooks (an amazing collection of images and notations set on black album pages now housed at the Oregon Historical Society) and you’ll see it there on a table, in the corner of a room, sometimes in use.

Terry O’Hanlon has been a member of the club since 1962 and has watched the neighborhood, and the club, change. When she joined, average club membership was a bit older than today, with most members between their early 50s and 80s (she was one of the youngest when she joined, in her 30s). Today, O’Hanlon is the eldest club member, and the youngest member is in her mid 40s. She also remembers Alameda filled with more young families and young children. Not so today, with plenty of two-parent working families.

“The pressures on professional women are different today than in my day,” she says, reflecting on the forces that have shaped the club over the years. “If you are working 40 or 50 hours a week, it’s hard to make it to an afternoon meeting like ours.”

Still, the friendship and camaraderie of the club—and its core philanthropic mission today—create a special sense of purpose that continues to fuel club meetings and activities. The tie to tradition, a respect for generations of Alameda women, and a real love for the neighborhood, distinguishes this special group.

-Doug Decker