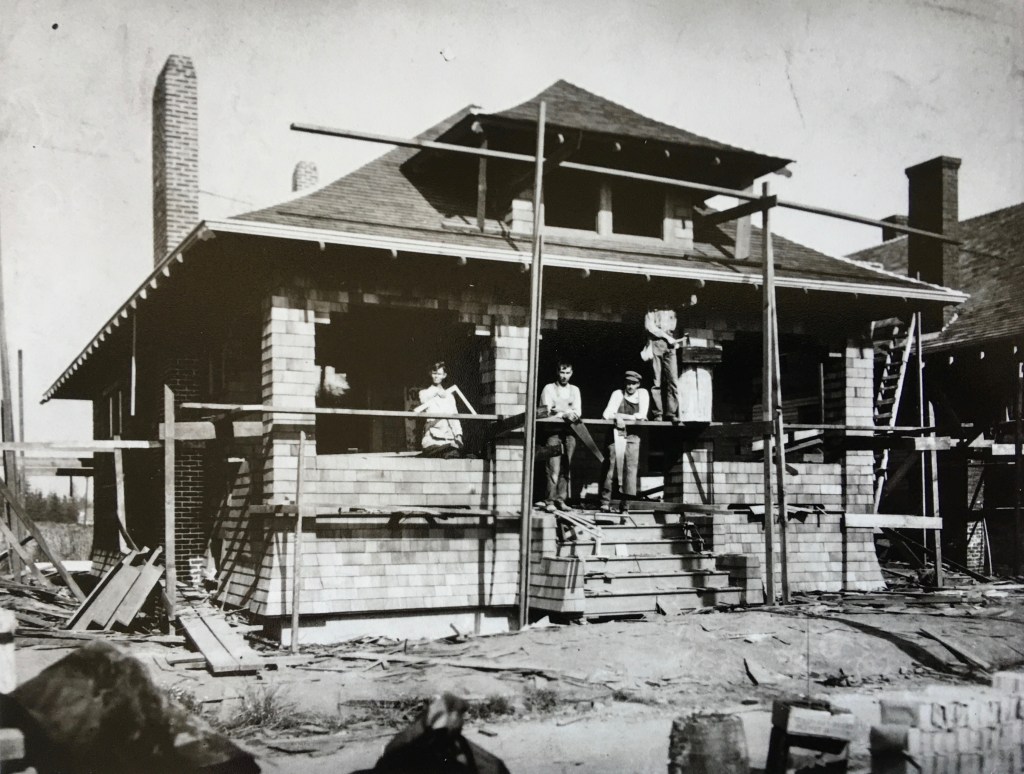

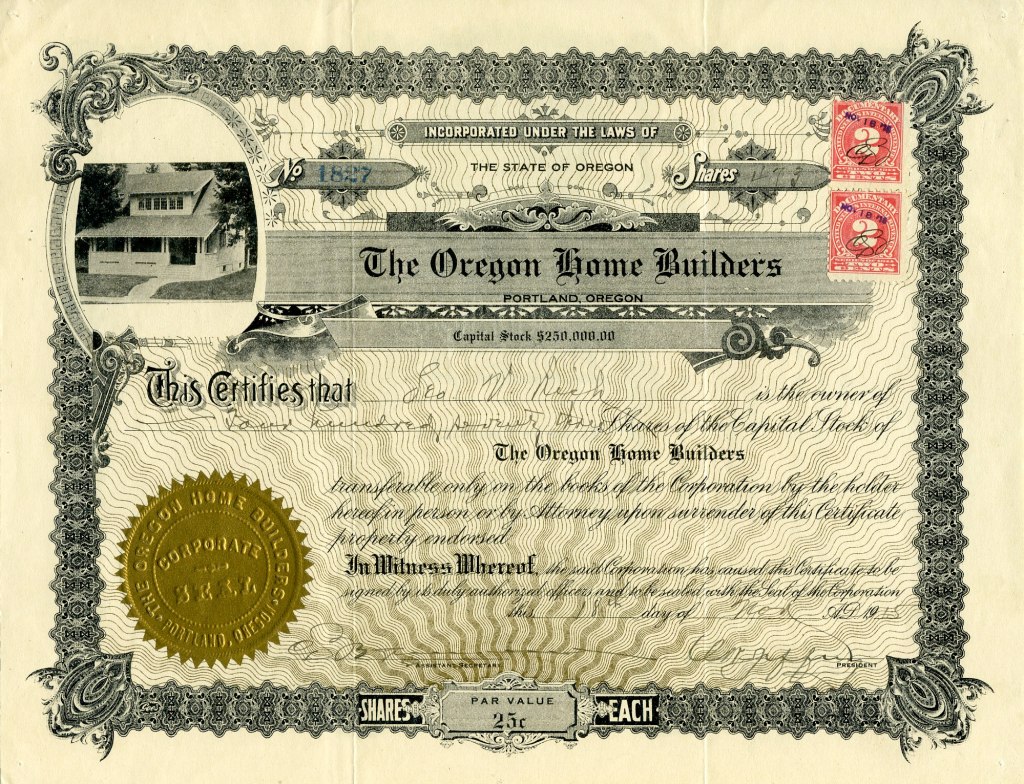

We’ve been exploring the early history of the 1913 Arts and Crafts bungalow at 2503 NE Mason—one of the three we wrote about last week—and the plot has thickened. Its builder, a relocated Canadian citizen, Colorado miner, and livery stable owner, moved to Portland in 1911 and became a home builder, ship builder, all-around handyman and eventually a property developer working on projects in the Hollywood area and near Mt. Hood.

According to building permit and real estate records, Sterling A. Rogers started excavating the basement the very same week he bought the vacant lot in the recently platted Alameda Park addition for $823 in May 1913.

Sterling and wife Lena had arrived in Portland in 1911 after selling their horses, home and livery business in Dunton, Colorado to his brother Robert. Sterling and Lena, then 29 and 26 respectively, had enough of the hard winters in the San Juan Mountains of southwestern Colorado. After a winter escape to the West Coast in 1909, they must have decided it was time to leave. Sterling had been a kind of renaissance man in Dunton, locating mines, constructing buildings, acquiring and looking after horses and wagons.

The Telluride Daily Journal described him like this in its May 23, 1903 edition:

Sterling Rogers, postmaster, merchant, hotel proprietor, and all around monopolist, of Dunton, was an arrival from the south on last evening’s train. He remained overnight and left this morning for Denver. He says that owing to the horrible condition of the roads between the Coke Ovens and Dunton, he cannot get enough lumber to put the finishing touches on his new hotel, but expects to be able to move into the building within the next two or three weeks.

Sterling finished the hotel, and added a pool and baths at the nearby hot springs, but in early 1911 the couple left for Portland. By December, he and Lena were buying vacant lots in the Vernon and Woodlawn neighborhoods. If the hard Colorado winters didn’t drive them out, could be they saw the writing on the wall: by 1919, Dunton had become a deserted and dilapidated ghost town, sidelined by its remoteness and primitive transportation connections, which Sterling knew all too well.

Rogers finished the Mason Street bungalow in August 1913 and advertised it for lease for $30 per month through the fall and early winter while the couple lived there:

From The Oregonian, January 18, 1914

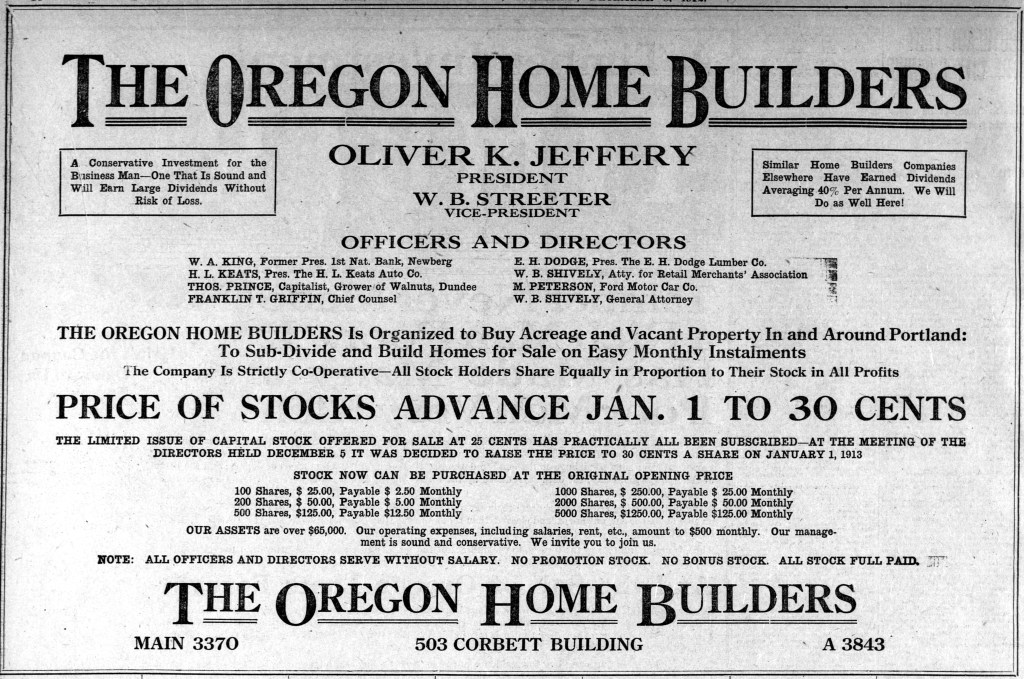

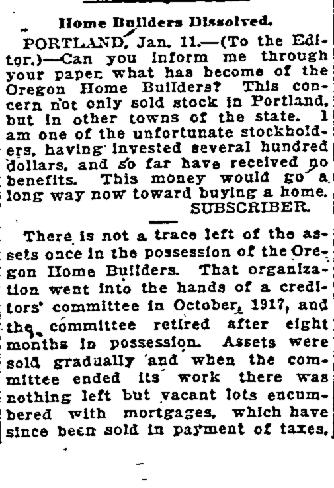

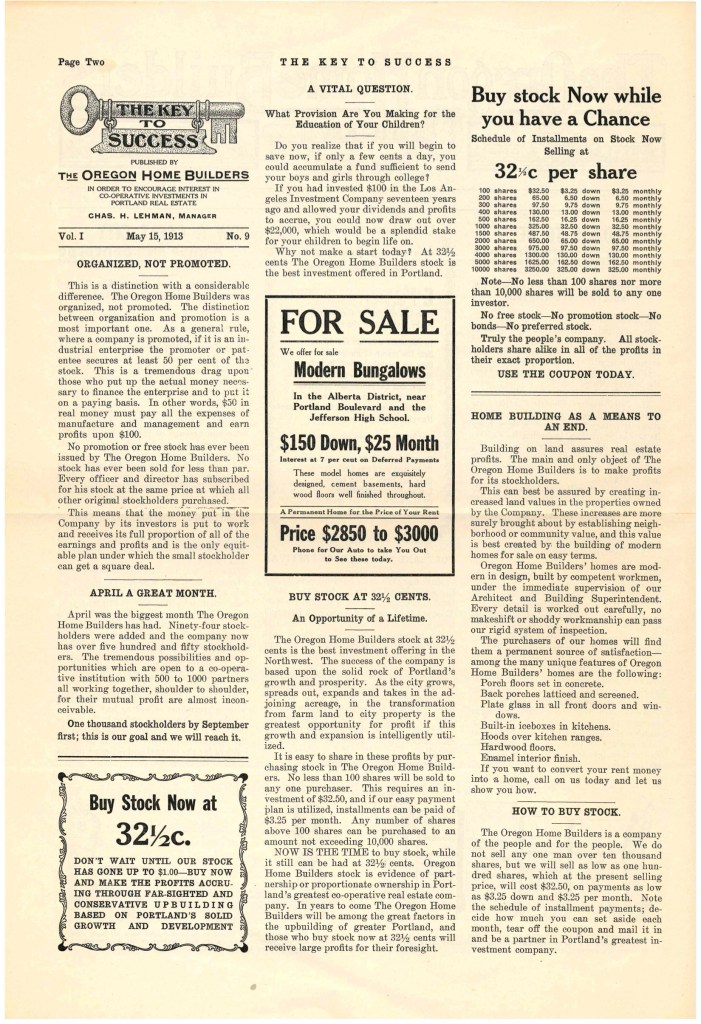

Like many young Portland builders of that time, Sterling was trying to leverage financial momentum by living briefly in his brand-new house built on speculation, leasing or selling it quickly, and using the proceeds to fund other projects that could lead to a next-level income. The couple continued to buy, trade for, and seek additional vacant lots on the eastside. In the spring and summer of 1915, Sterling the entrepreneur was busy:

From The Oregonian, May 9, 1915

From The Oregon Journal, August 8, 1915

Sterling was not a butcher. The meat market had belonged to Daniel and Ethel Dyer, who not coincidentally had moved into the Mason Street house for about a year in 1916, under what must have been a creative financial agreement. But that didn’t last, and by 1917, Sterling and Lena were back. And according to auto registration records, they had indeed been accumulating quite a few vehicles, all registered to the Mason Street house.

In 1918, at age 35, Sterling registered for the World War 1 draft and gave his occupation as a ship carpenter (as well as his height at 5’9”, weight at 140, blue eyes and black hair) and home address as 801 Mason, today’s 2503. That year, he also petitioned for citizenship and renounced his allegiance to George the Fifth, King of the United Kingdom and the British dominions. Rogers had been born in the Canadian province of Prince Edward Island (Canada was then under the dominion of Great Britain). Lena was from South Dakota.

Meanwhile, the couple had been buying property along Sandy Boulevard and by 1920 they moved to a home long since torn down at the northeast corner of 43rd and Sandy. Sterling continued to speculate in real estate, take on repair jobs and build small bungalows—none as distinctive as the Mason Street house. In 1933 it looked like he was going to make it big with a planned development of summer homes on Mt. Hood (which sounds a lot like what is today’s Brightwood).

From The Oregonian, May 21, 1933

But the Great Depression of the early 1930s was a hard time to be building or selling anything. Sterling died of tuberculosis in 1936; his death certificate showed he had struggled with the disease since the mid 19-teens.

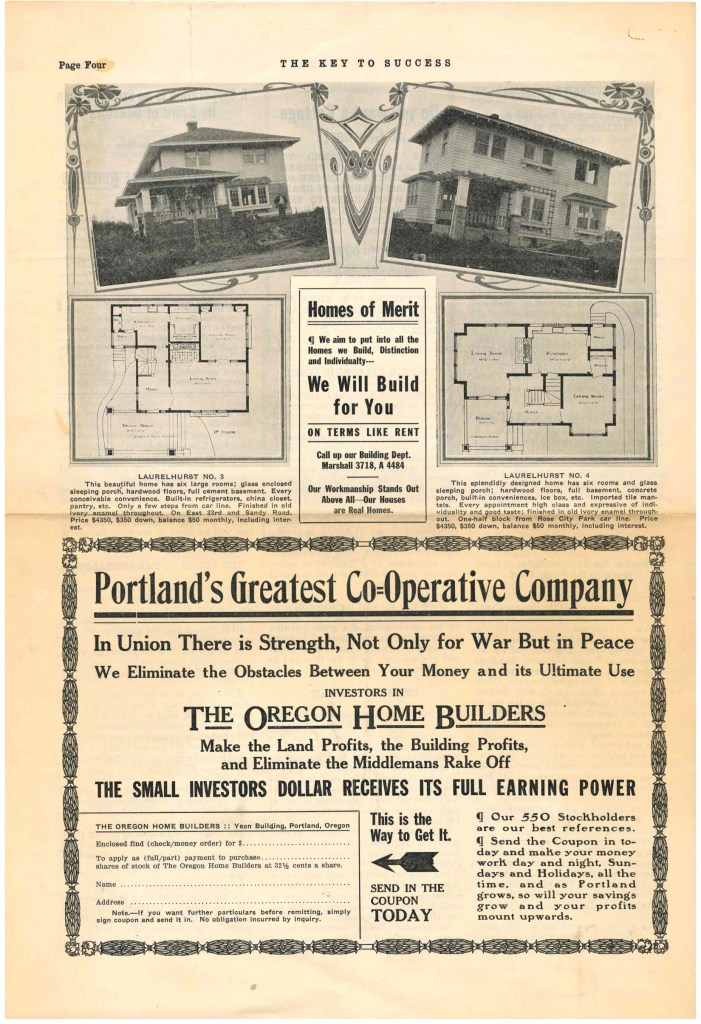

Rogers built it – Who designed it?

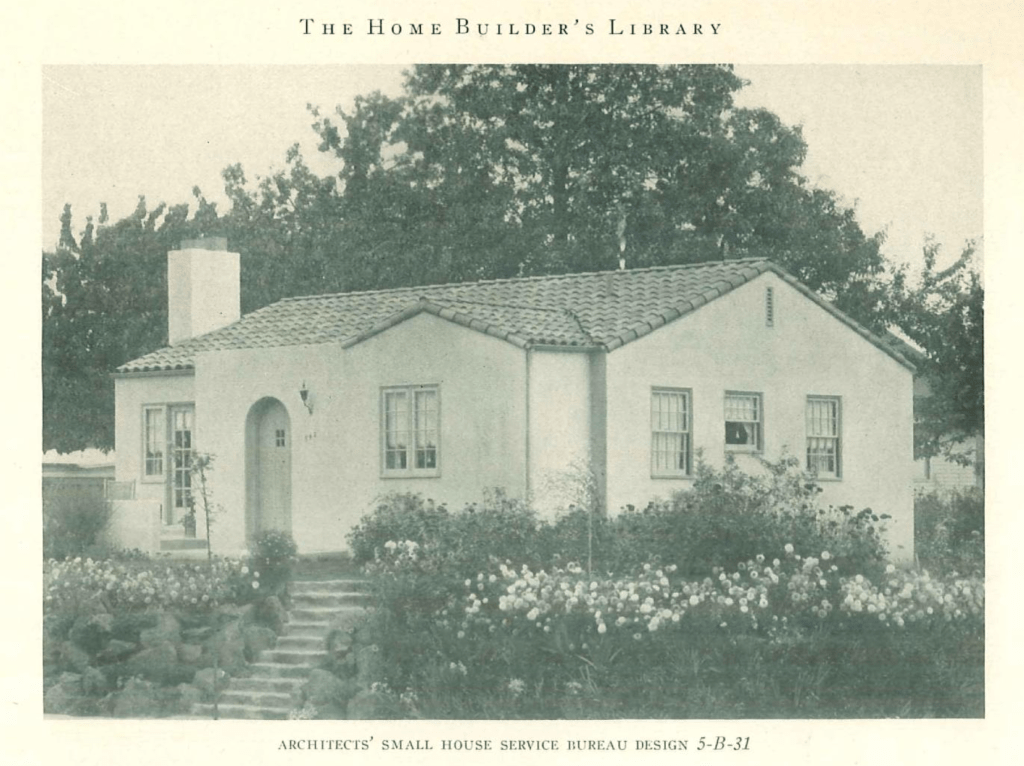

A look at the handful of relatively non-descript bungalows Sterling built in the 19-teens and 1920s—absent decorative trim, built-ins, columns or beveled glass—makes us think 2503 is a kit home, meaning he bought it as a package to be assembled, which was relatively common then. The design-forward detail of 2503 (see for yourself) is so unlike anything else he built.

So we’ve been poring over kit house and plan set catalogs looking for family resemblances. The external door and window trim is distinctive on this house, as are the three long beveled glass panel interior and exterior doors. Haven’t found it yet, but we’ll keep looking.

Having researched many early home builders, we’re well acquainted with the blend of boot-strap, hard-scrabble entrepreneurship they and their families brought to the building of our neighborhoods.

The homes we live in—the materials they are built with, and the people who did the building—are from a different era that’s hard to imagine today. Each of our homes has its own origin story, the windows, walls and ceilings shaped by people whose stories we’ll never know.

But it’s been fun getting to know Sterling.