Here’s a neighborhood walk that makes a nice outing and puts you on the well-worn pathway of earlier years—a history-hunt of sorts to bridge past and present and imagine a time when Alameda was younger and connected to downtown courtesy of the clanky, drafty, dependable Broadway Streetcar.

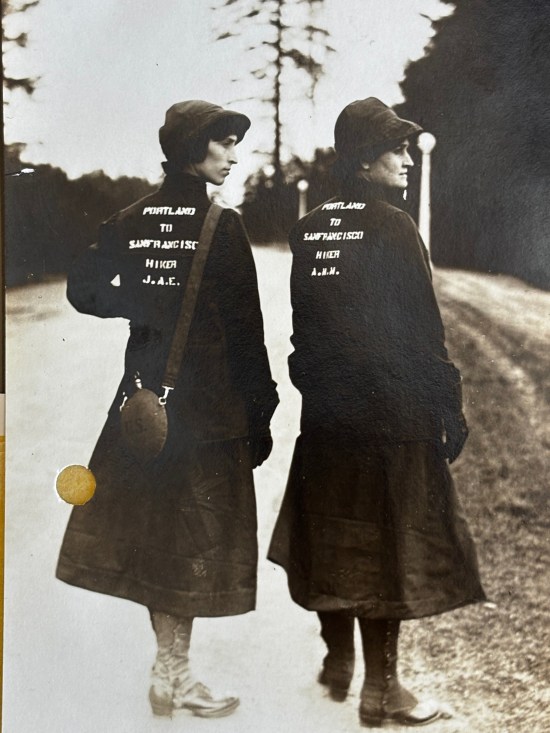

Broadway Streetcar 568 at the end of the line, 29th and Mason. This photo was taken soon after the line was built in 1911, prior to construction of homes and infrastructure.

You can enter this walking loop just about anywhere on the course of the streetcar’s roundabout transit through the neighborhood, and you can head either north or south. But, just to be orderly about it, how about starting at the end of the line: NE 29th and Mason. That’s where the Broadway streetcar stopped, where the motorman would step outside for a smoke and a look at his watch.

Here’s the same view at NE 29th and Mason, about 1912-13. Note paved streets, absence of mud and brush, and presence of two buildings. The house to the left stands today and is 4206 NE 29th. The building on the right was the Alameda Land Company tract office (a temporary structure at the southeast corner of the intersection), where prospective buyers who exited the streetcar could meet with salesmen and look at subdivision maps. Check out this post which has other views of this intersection and more about the early Alameda Park neighborhood.

From the end of the line, walk south on 29th to Regents, where the streetcar passed through the “Bus and Bicycle Only” notch at Regents and Alameda. The streetcar turned right and went down the hill here, and you should too, following Regents to NE 24th Avenue where you’ll turn left (south). Continue south on 24th to Fremont and then turn right on Fremont to go west for a couple blocks, just like the old 809 shown below. See if you can orient yourself in just about the same place.

Broadway line car 809 rounds the corner at 24th and Fremont, looking east, 1940. Courtesy of Portland City Archives A2011-007.65. Click to enlarge for a better view. The Safeway building is today’s bank and Alameda Dental. The sign for Alameda Drugs is hanging on the side of today’s Lucca restaurant. Here’s a link to more views of the intersection at NE 24th and Fremont.

At NE 22nd, turn left (south) and enter the long southbound leg of the circuit. Note just how wide the street is: a clue that you are on the streetcar route.

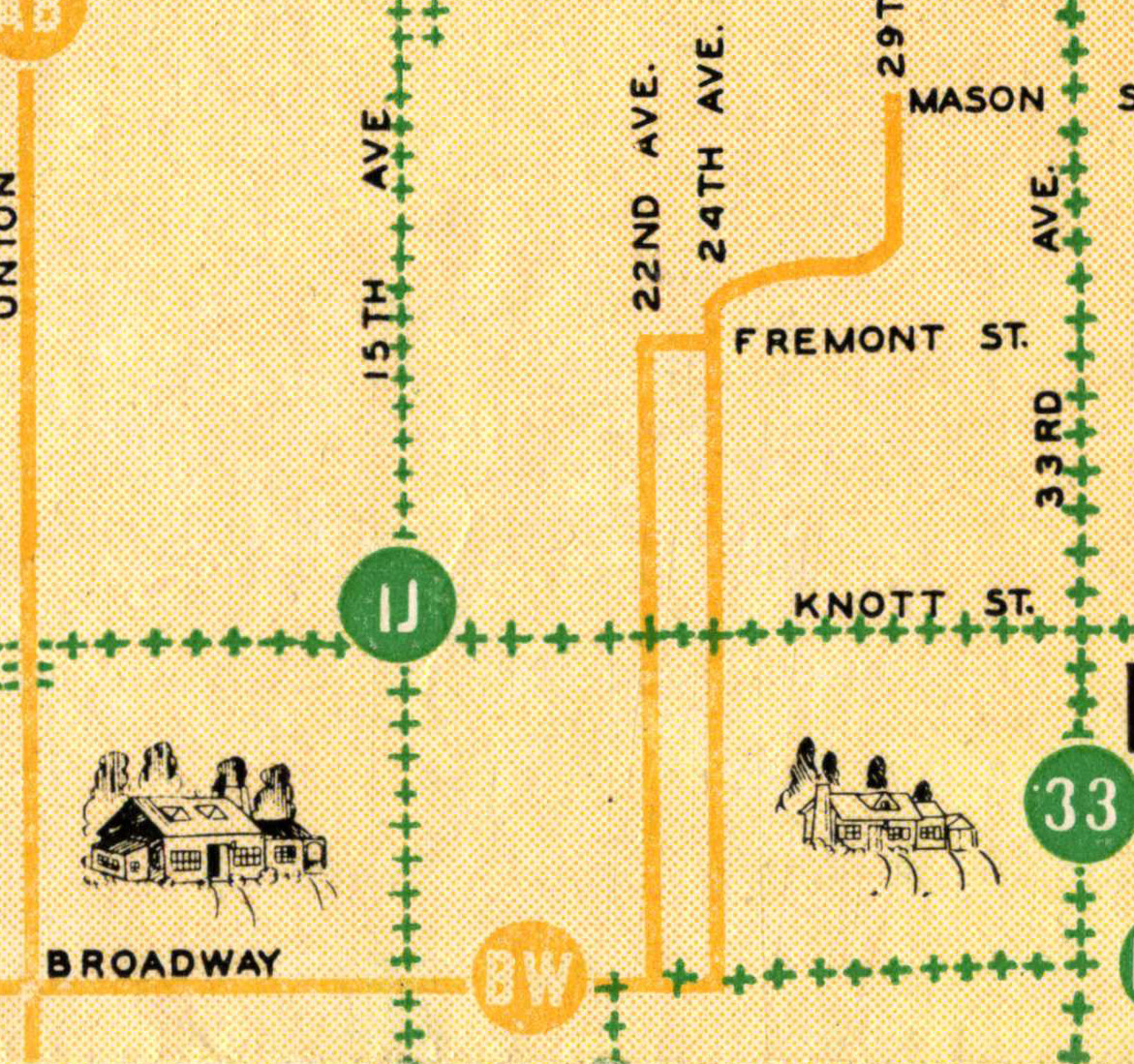

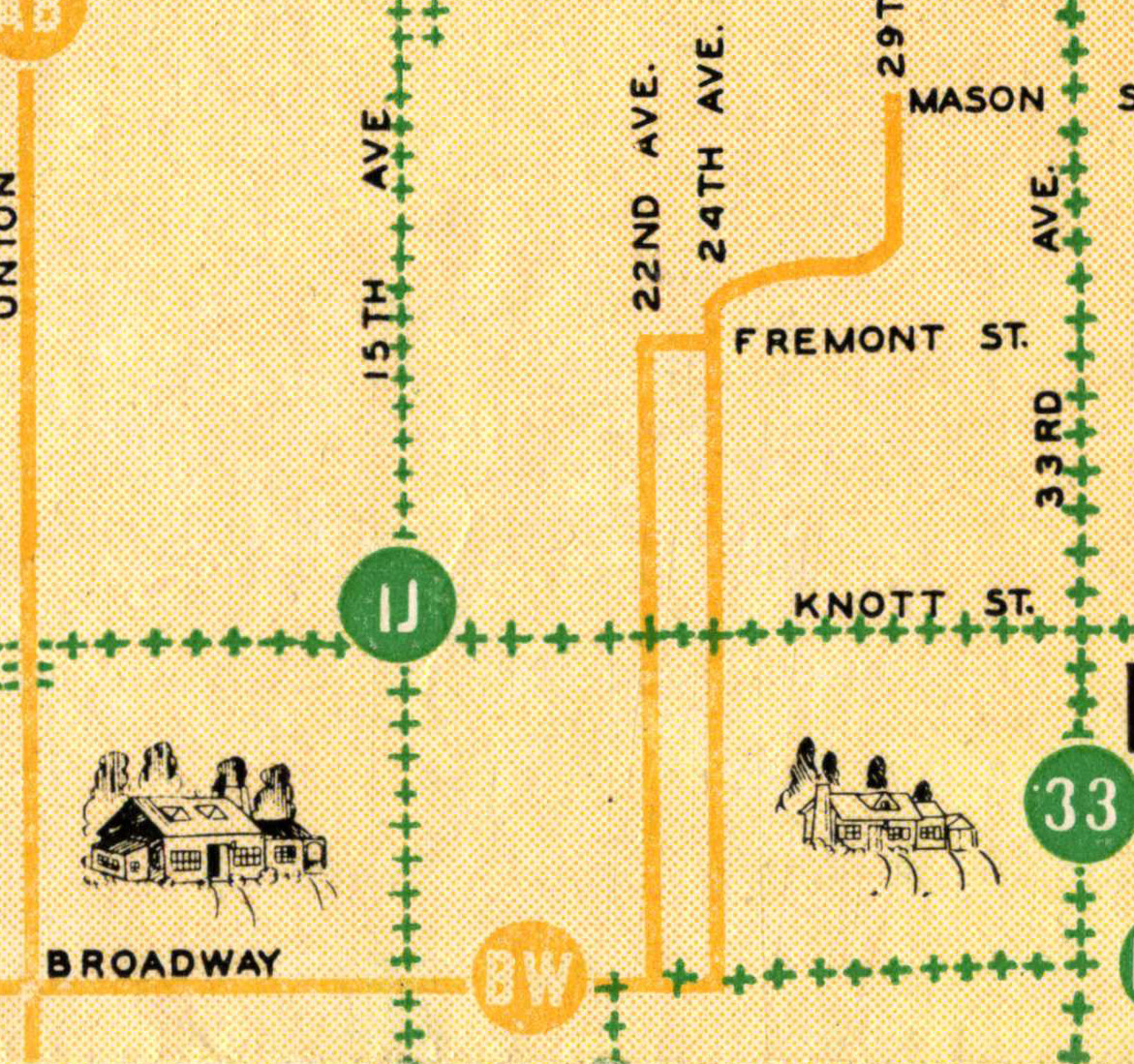

Detail from 1945 Portland Traction Company Map. The green + signs illustrate bus lines. The yellow lines are streetcars. By 1948 Portland’s streetcars had all been removed.

After a good, long straight stretch, when you hit Tillamook and 22nd, you’ll find a modest “S” curve, where the streetcar zigged and zagged on its way south to connect with Broadway. Follow along just for fun. But instead of turning west on Broadway (right) like the streetcar did on its way downtown, turn left (east) and walk back to NE 24th, where you turn left (north) and head back through the neighborhood. Now you’re back on the path of the Broadway Car—the northbound side of the circuit—and headed toward the end of the line.

Believe it or not, this is looking southwest at the southwest corner of Broadway and 24th in the summer of 1929, before Broadway was widened. See the streetcar rails sweeping from west to north here in the lower right corner? This service station sits where Spin Laundry Lounge is in 2018. The man holding the number works for the city; the number designates that tract of property for further reference. Click to enlarge. Courtesy of City of Portland Archives, image A2209-009.3407.

Continue north on 24th, cross Fremont and turn right (east) on Regents, where you go back up the hill on your way to the end of the line. Here’s a cool view of NE 24th and Fremont looking north, taken in about 1921. Can you line up in the footsteps of the photographer? The houses you can see in this 1921 photo are still there today.

NE 24th and Fremont looking north, taken in 1921. Courtesy of Portland City Archives, image A2009-009.1858

At the top of Regents, pass through the bus notch again and go a few more blocks to Mason, and you’ve arrived at the end of the line. Here’s a photo looking south on NE 29th, from the southeast corner of Mason. See if you can line up in the footsteps of history: pretty much everything but the streetcar and the rails are still visible today.

Turn-by-turn:

Start: 29th and Mason

- Walk south on 29th to Regents, turn right and go down the hill.

- At 24th, turn left (south off of Regents).

- Walk to Fremont and 24th, turn right on Fremont (west off of 24th).

- Walk two blocks on Fremont and turn left on 22nd (south off of Fremont).

- Keep walking south on 22nd to Tillamook.

- Navigate the zig-zag at Tillamook and stay south on 22nd to Broadway, turn left (east off of 22nd).

- Walk east on Broadway to 24th, turn left (north off of Broadway).

- Walk north on 24th, crossing Fremont, and turn right on Regents (east off of 24th).

- Walk up the hill on Regents to 29th, turn left through the notch (north off of Regents).

- Walk north on 29th to Mason and you have reached the end of the streetcar line.

- Tip your hat to the motorman and the generations of Alamedans who depended on this train.

Some things to look for on your walk…

Notice how 29th narrows on the north side of the intersection. The wider stretch of street to the south was necessary to accommodate the rails and the traffic. Have a good look at Northeast 22nd and you’ll notice how much wider it is than any of our north-south streets. There are other clues to be found in the alignment of power poles, and in the remnants of rail unearthed from time to time during street repairs.

A little more history about our streetcar…

Two generations of our neighbors grew up relying on the Broadway streetcar to take them where they needed to go. Ever-present, often noisy, sometimes too cold (or too hot), but always dependable, the Broadway car served Alameda loyally from 1910 to 1948.

Sensitive to the transport needs of its prospective customers, the Alameda Land Company financed construction of the rails and overhead electric lines that brought the car up Regents Hill to 29th and Mason. Developers all over the city knew access was one key to selling lots, particularly in the muddy and wild environs that Alameda represented in 1909.

In 1923, a trip downtown cost an adult 8 cents. Kids could buy a special packet of school tickets allowing 25 rides for $1. In 1932, a monthly pass for unlimited rides cost $1.25. Alamedans used the streetcar as a vital link to shopping, churchgoing, commuting to the office, trips to the doctor. Some even rode the line for entertainment. A few rode looking for trouble. And at least one elderly rider frequently took a nap in the front yard at the end of the line while waiting for the streetcar.

During the day, cars ran every 10 minutes, and Alamedans referred to them as “regular cars” or “trains.” During the morning and evening rush hours, additional cars called “trippers” were put into the circuit to handle additional riders. Trippers did not climb the hill to 29th and Mason, traveling only on the Fremont Loop to save time. At night, our line was one of the handful in Portland that featured an “owl car,” a single train that made the circuit once an hour between midnight and 5 a.m. Owl service was a special distinction. The downtown end of the line was Broadway and Jefferson.

The Broadway streetcar was replaced by bus on August 1, 1948. By 1950, all of Portland’s once ubiquitous streetcar lines were gone. In the early days of neighborhood life, our streetcar was indispensable. It was one catalyst that made development of Alameda possible. It linked us to downtown and to other neighborhoods near and far. To hear the stories of those who rode it frequently, it linked us to each other in a way too.

Here are a few other history walks you might enjoy.