Last weekend marked the final public tour of the A.L. Mills Open Air School at the southwest corner of SE 60th and Stark in the Mt. Tabor neighborhood.

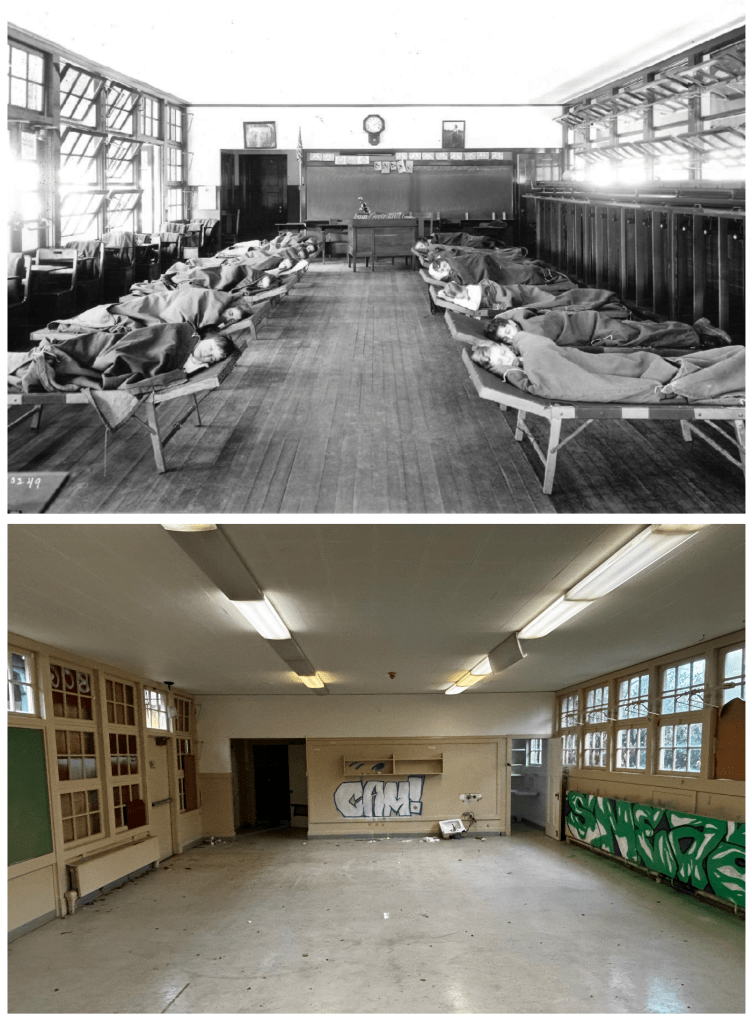

The empty long hallway at Open Air School, December 2024. The building has been empty since 2019.

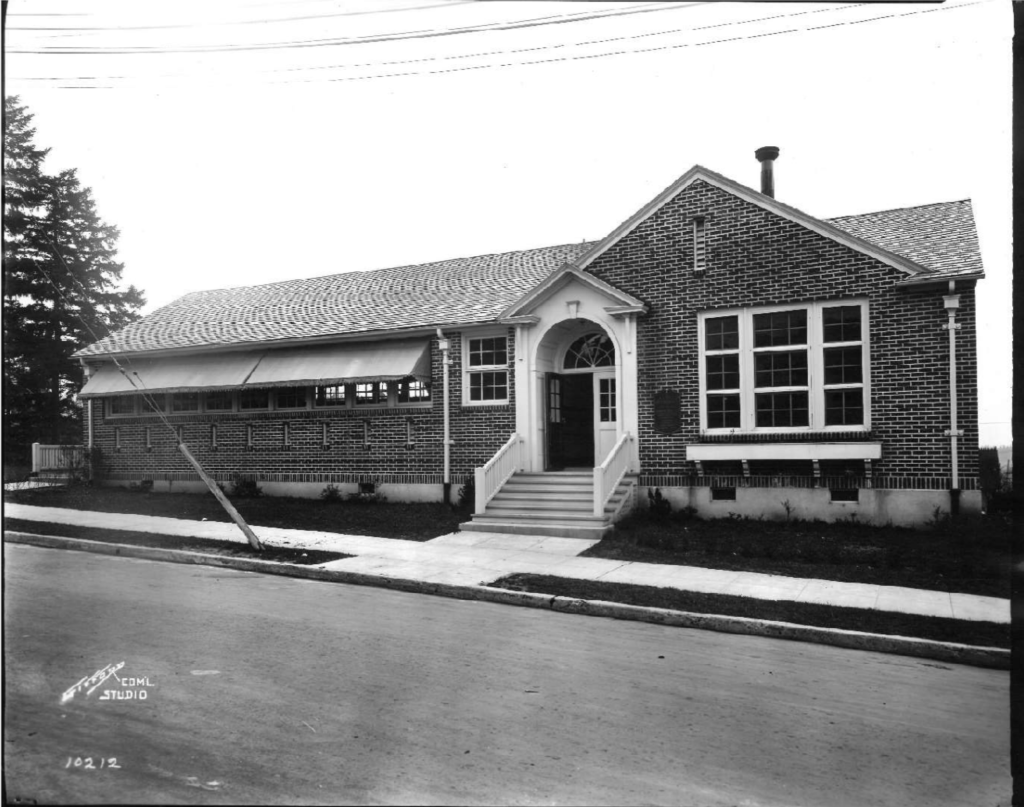

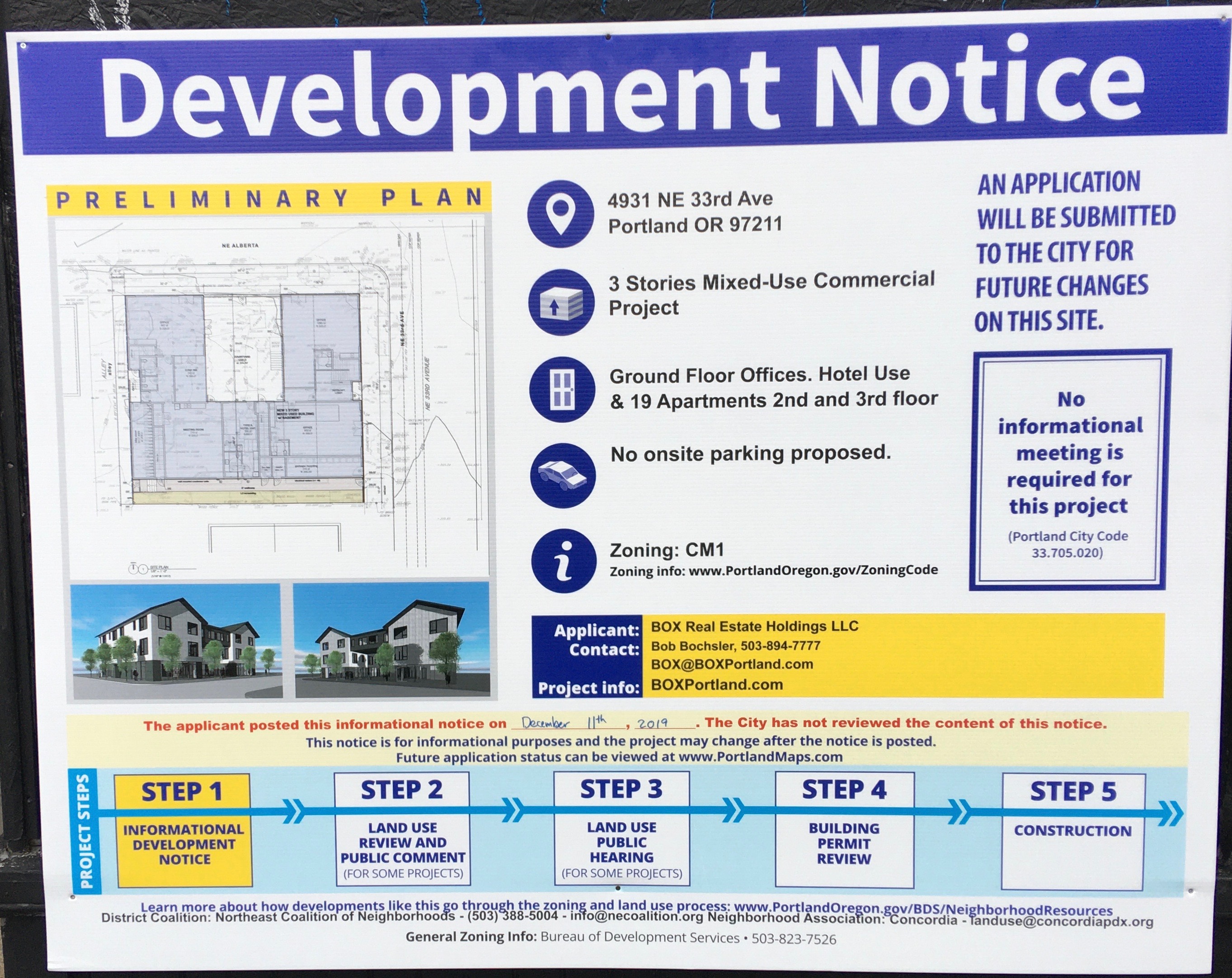

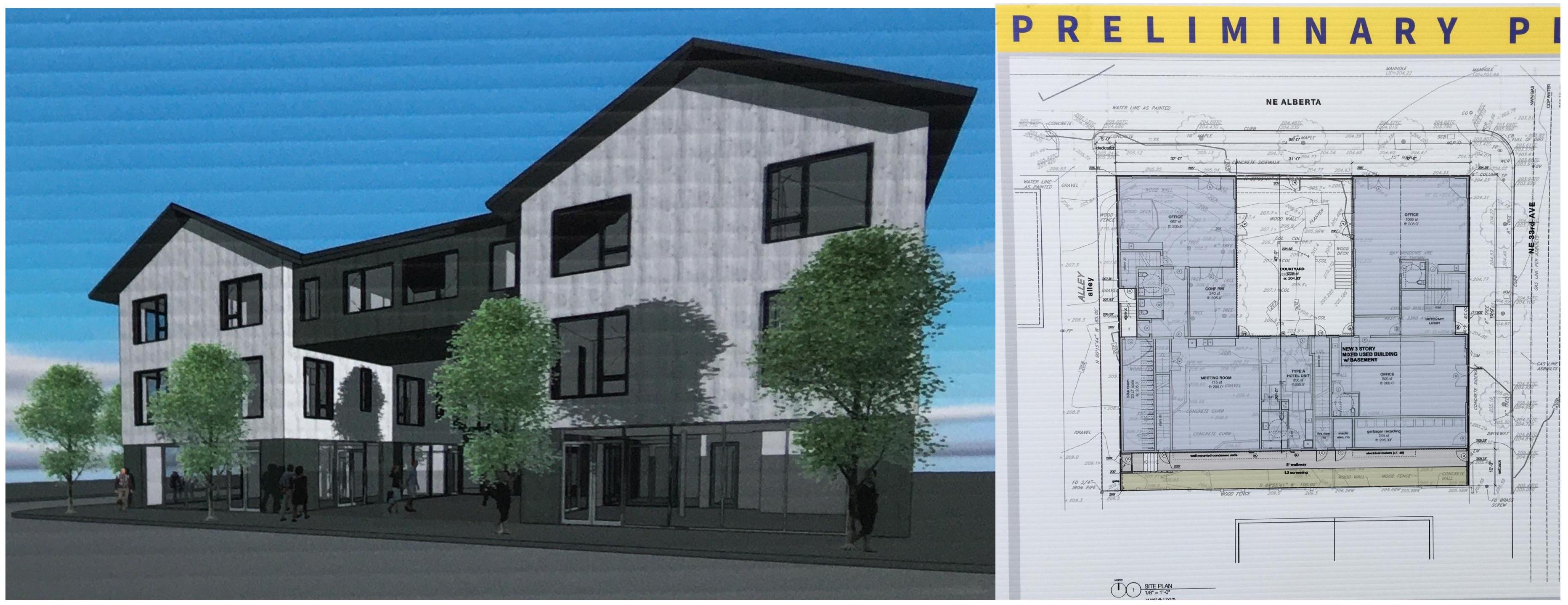

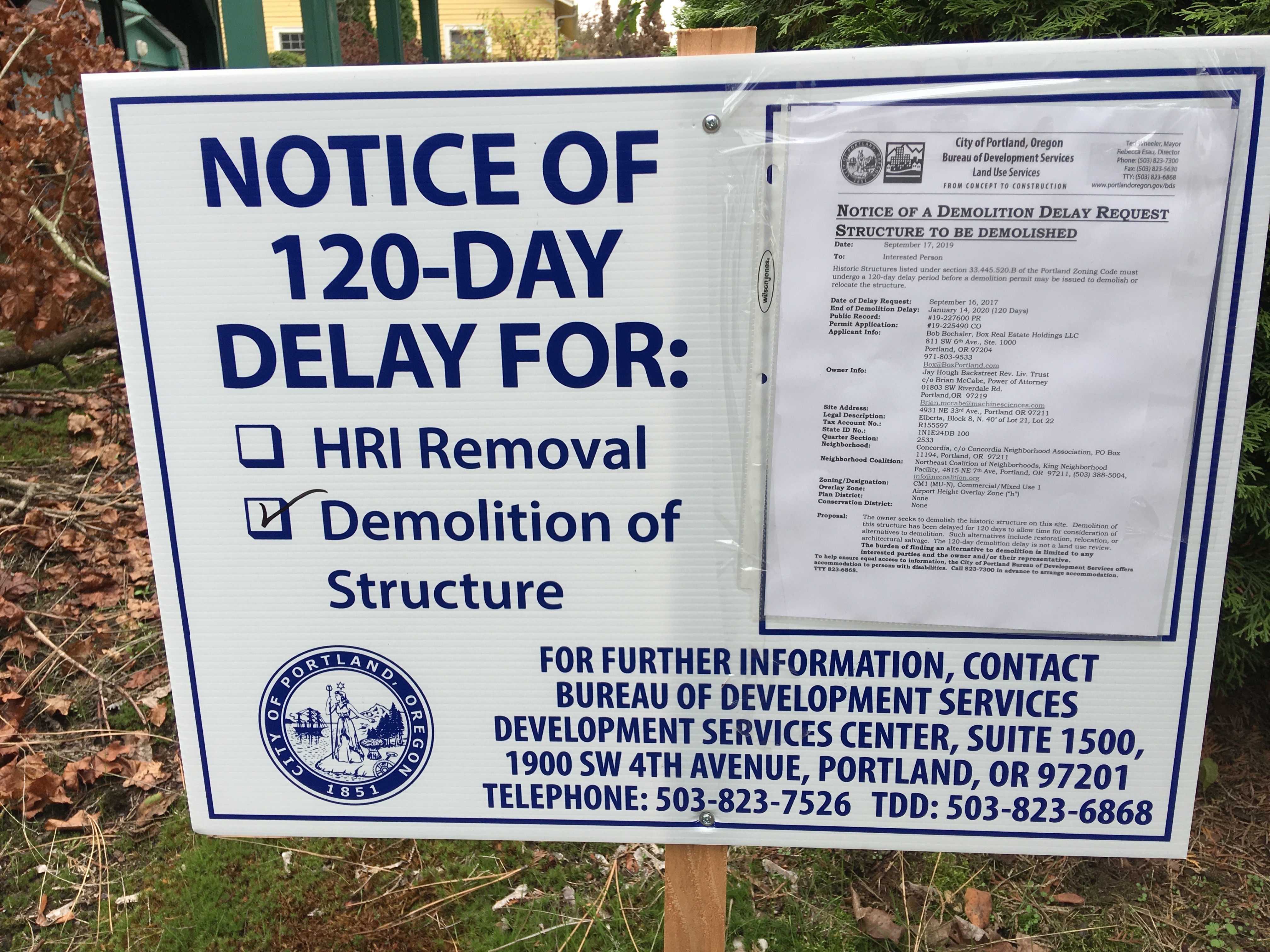

The former school building, built in 1918-1919, will soon be deconstructed by the Portland Housing Bureau (PHB) to make way for an affordable housing development. For the last six weeks, we’ve been working with the Bureau and the Mt. Tabor Neighborhood Association to share stories of the building with neighbors and anyone interested in having a last look.

Some came because they’ve watched the old school’s recent decline, seen the graffiti and cyclone fence sprout and wondered what was inside. Others came because they’ve had connections to one of the four chapters of its earlier life. Everyone wanted to know what would come next.

A.L. Mills Open Air School first of its kind

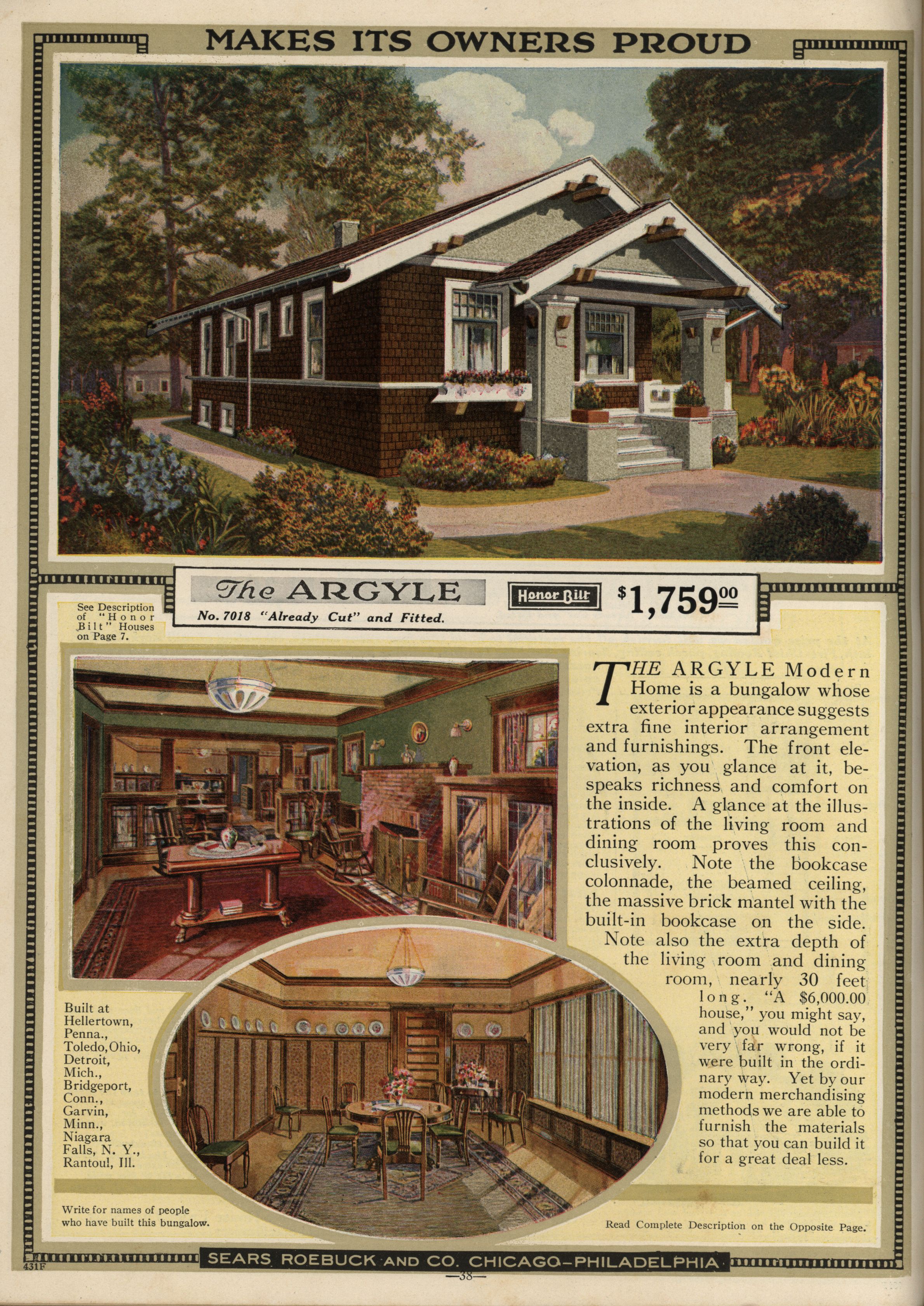

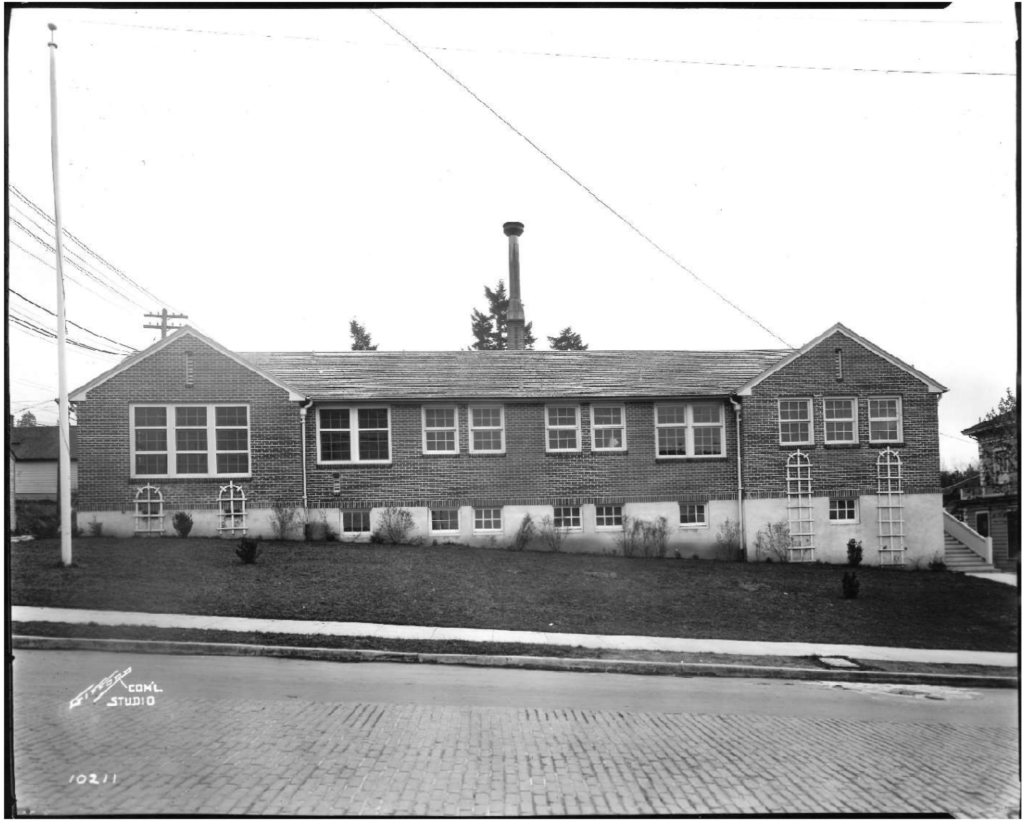

When it opened in 1919, the Abbott L. Mills Open Air School put Portland on the map nationally and internationally as the nation’s first entirely purpose-built open-air school, meaning that students and teachers spent their entire school day surrounded by fresh air. A handful of other communities across the country had experimented with a classroom here or there in an existing school. In Portland, the original Irvington School featured one open air classroom where the windows were open all day, all school year.

But with financial help and encouragement from the Oregon Tuberculosis Association, Portland Public Schools was able to build an entire school dedicated to helping “low vitality children” improve their health and therefore their resiliency to tuberculosis, which was a serious health threat of that era killing hundreds of thousands of people of all ages in the U.S. during the 1920s.

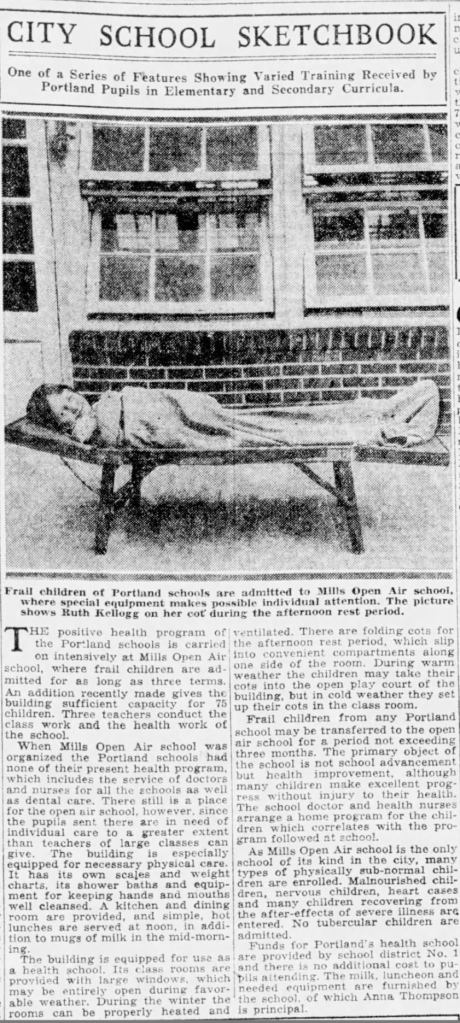

From the Oregon Journal, November 30, 1919

The Oregon Tuberculosis Association was led by Abbot L. Mills, former Oregon Speaker of the House, philanthropist, president of the First National Bank of Portland, and chief organizer of the Portland Open Air Sanatorium for Consumptives. Mills, who earlier served as vice president of the 1905 Lewis and Clark Exposition, was a tireless public health advocate around tuberculosis, and the chief push on funding for the school, so it’s entirely appropriate the building bears his name.

The open-air movement was an international public health philosophy based on the notion that being exposed to fresh, circulating air kept children, and people of all ages, healthier.

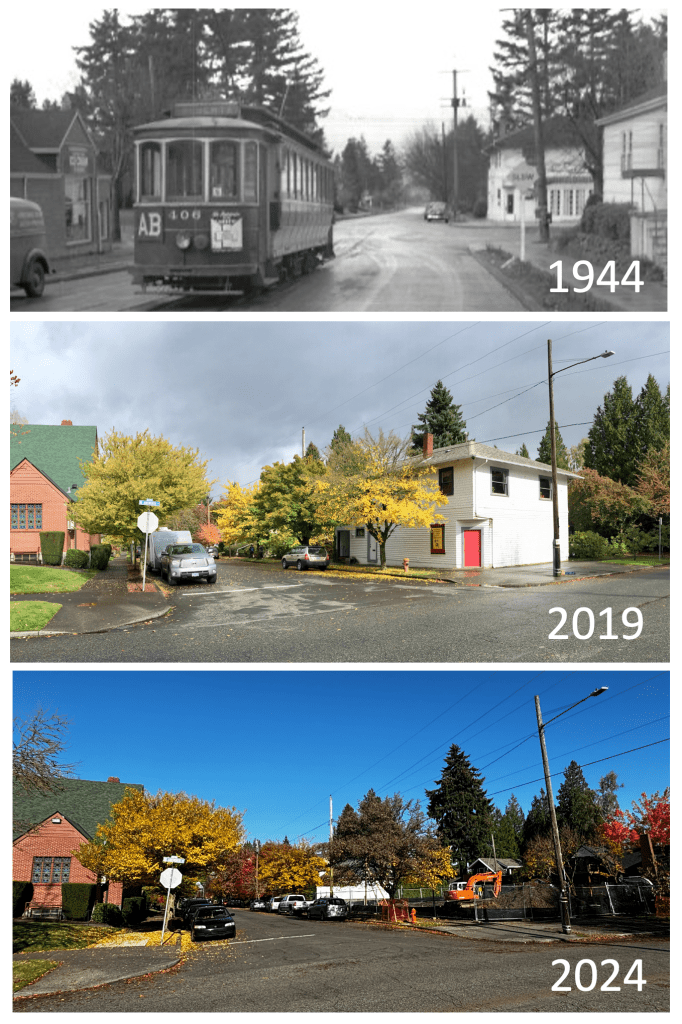

60th and Stark: Epicenter of Mt. Tabor community and Portland’s health spas

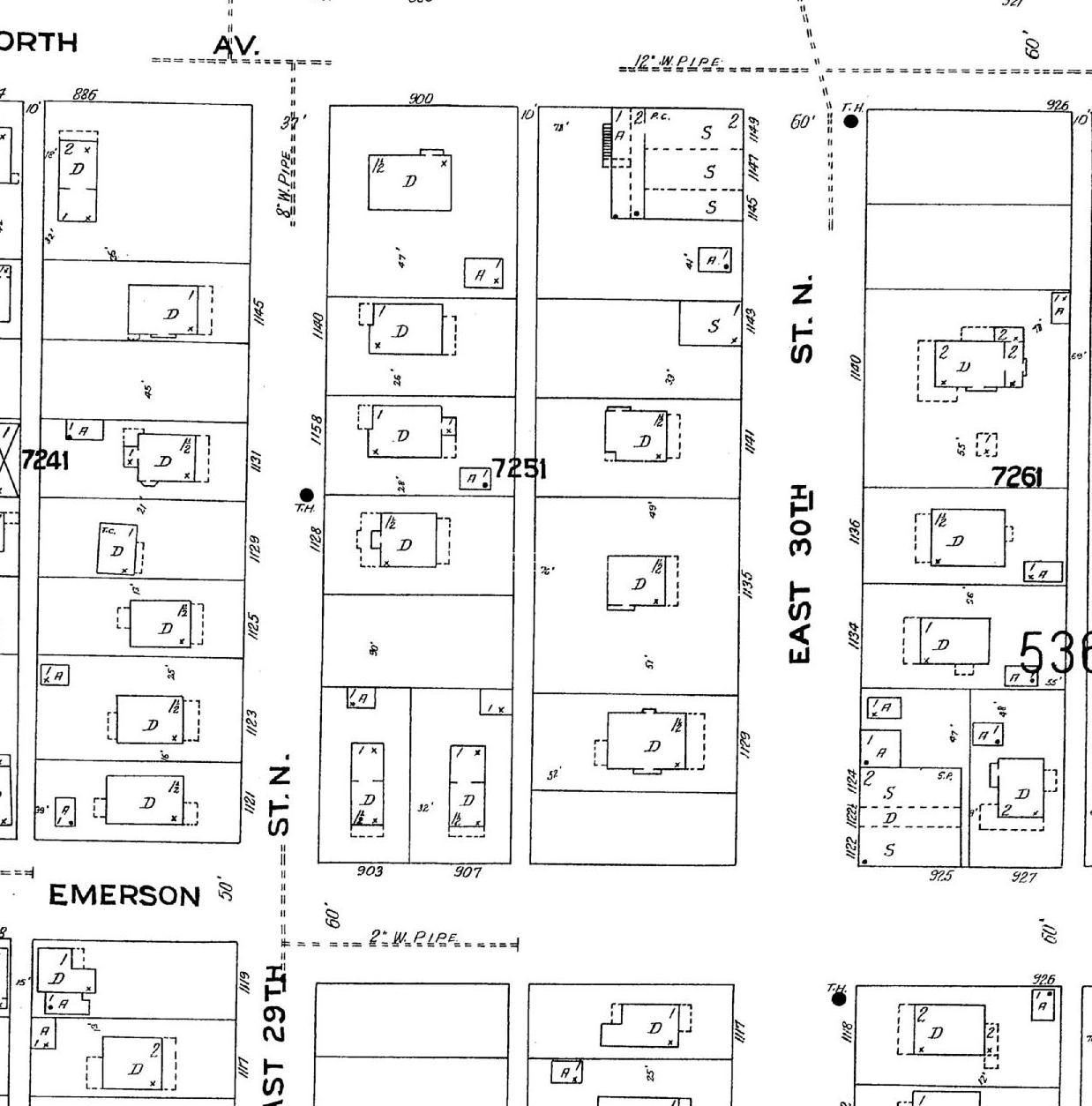

That’s why school and health officials selected the western slopes of Mt. Tabor, then a rural and bucolic elevated place distant from the churn of downtown Portland (Mt. Tabor was annexed into Portland in 1905). In 1902, the Portland Sanitarium opened just a block away at 60th and Belmont (site of the former Adventist Hospital). Another private sanitarium operated at 60th and Yamhill.

60th and Stark was also the crossroads and heart of the Mt. Tabor community. From 1880 until 1911 a former school operated on the site. Before that, a frontier school operated out of a log building in the same place.

Looking south on 60th at the corner with Stark (then known as Baseline Road), about 1907, four years before this school burned, clearing the site that has hosted the Open Air School since 1918. Drying cordwood is stacked for the furnace in the old school. Courtesy of the Oregon Historical Society, image Org-Lot-982, Box 8 Folder 6.

The two-room A.L. Mills Open Air School opened on January 27, 1919 with its full capacity of 50 students ages 5-15, two teachers and care team.

The Stark Street side of Open Air. Photograph Courtesy of the Oregon Historical Society, from the Ben Gifford Collection Box 8, Folder 5. Gifford photographed the school not long after its opening on January 27, 1919.

Miss Anna Thompson was principal of “Open Air,” its often-used nickname, and she never missed an opportunity to let everyone know her students were not tuberculous: they were children with health infirmities that made them vulnerable to TB.

Here’s an essay by Principal Thompson that appeared in The Oregonian on May 14, 1925:

“Because of the ardent interest and material support given by the Oregon Tuberculosis Association in the early history of the school, many people believe ‘Open Air’ to be a school for tuberculous children. This is a very grave mistake. Children who are tuberculous or infections from any cause whatsoever are not admitted. I want this fact impressed on parents and others. We are trying to prevent these children from growing into defective conditions–the purpose is preventative not remedial.“

Got that? Not a place for sick children: Miss Thompson and her colleagues were trying to keep them from getting sick.

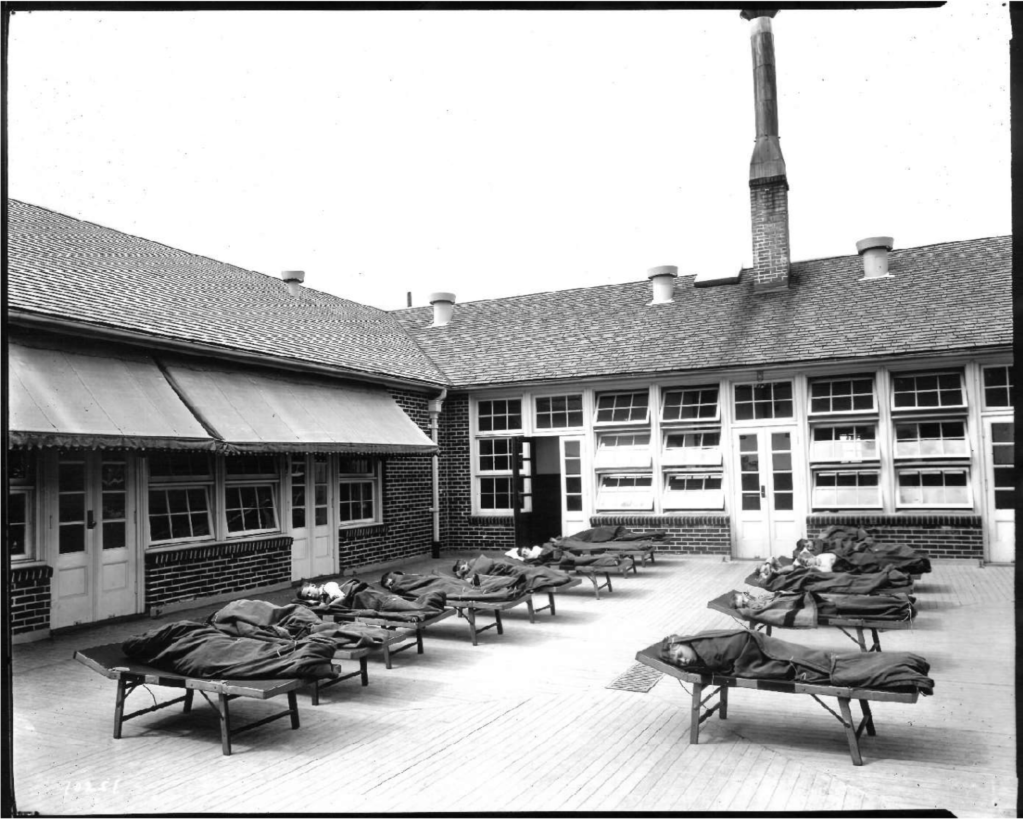

Afternoon nap time at Open Air. Photograph Courtesy of the Oregon Historical Society, from the Ben Gifford Collection Box 8, Folder 5.

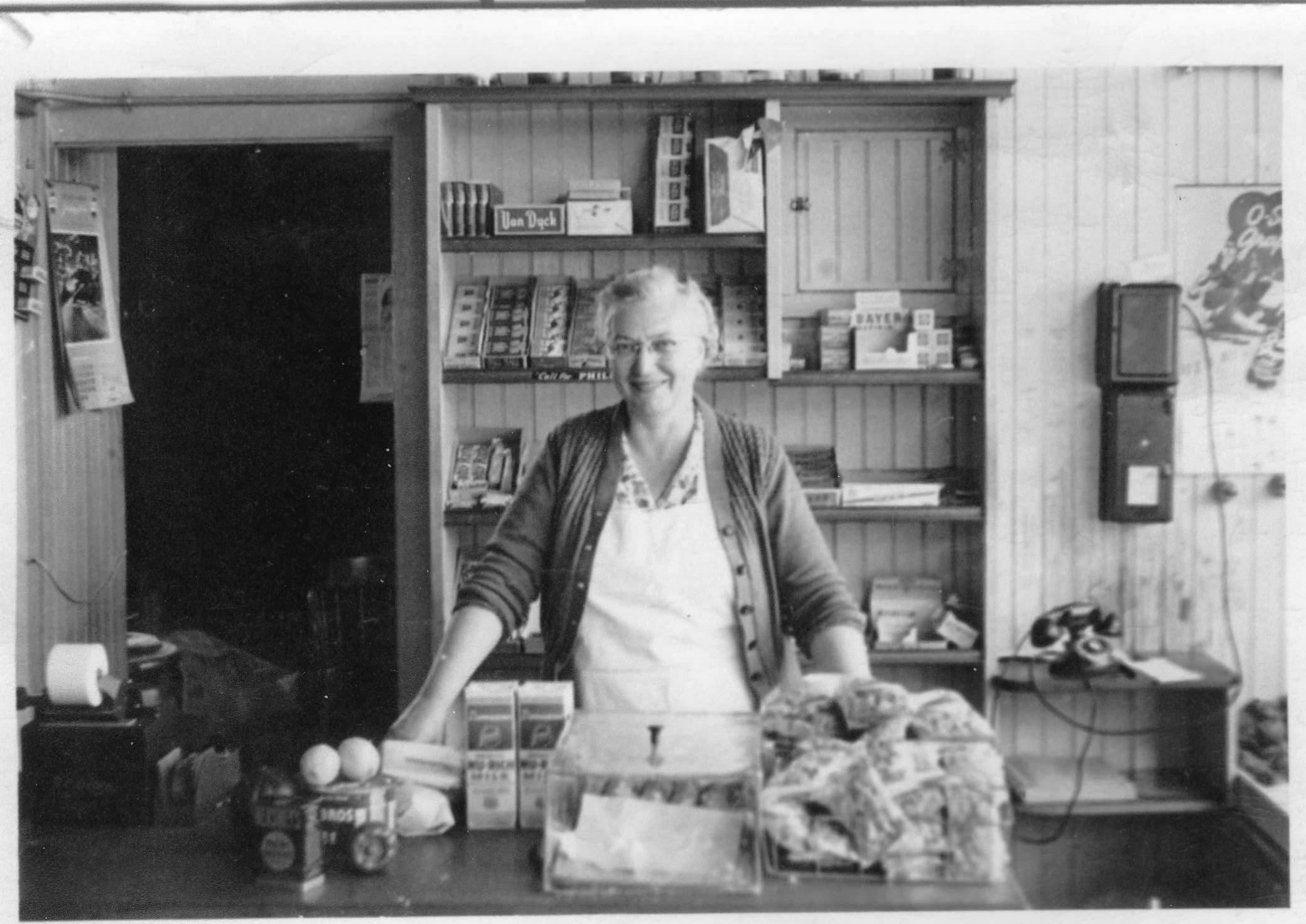

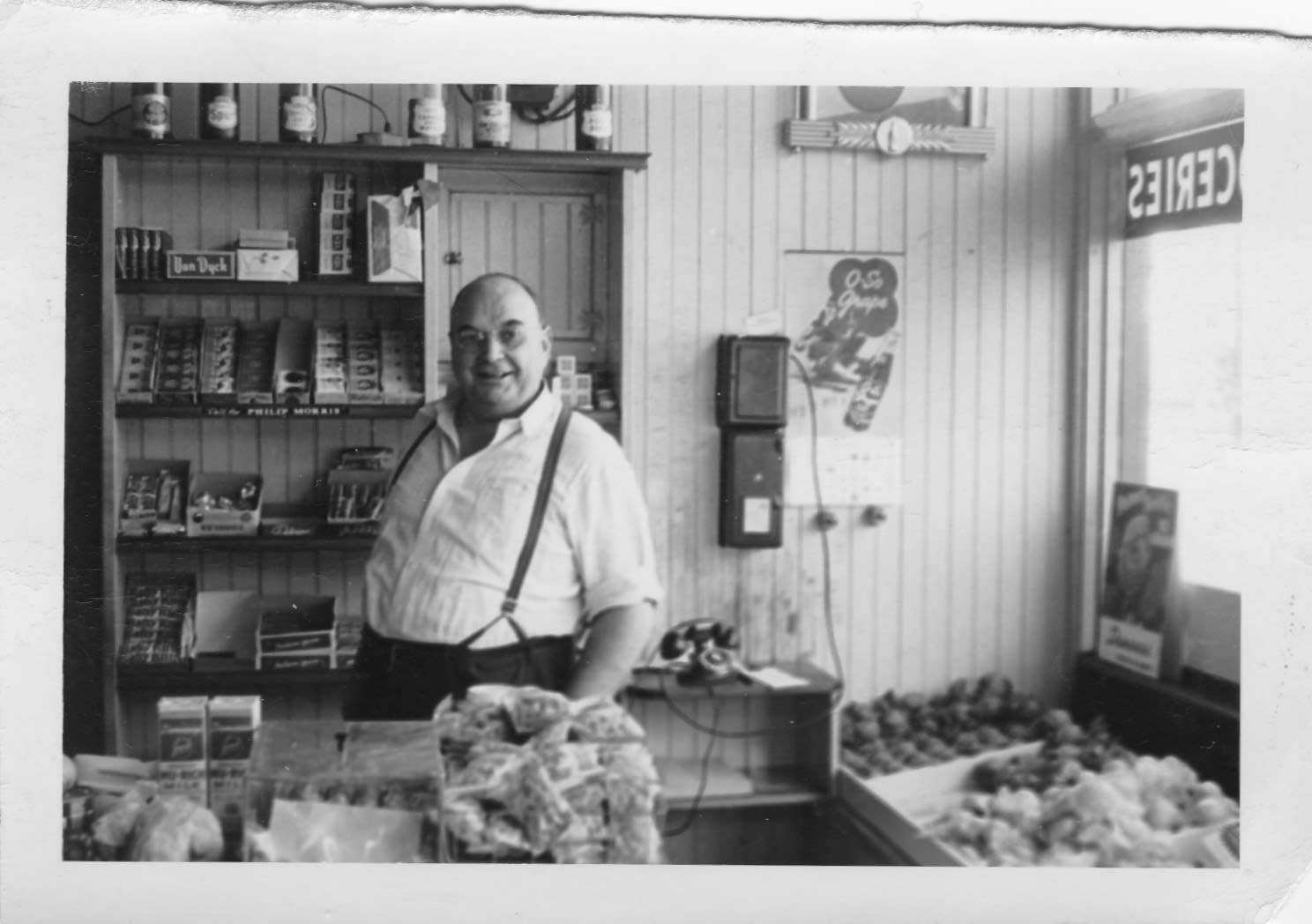

Staff at Open Air included Principal Thompson, who also taught in one of the two rooms; a physician who was on site every Wednesday to examine each child; a full-time nurse; a matron who helped with showers, hygiene and meals; and a second teacher. The nurse visited each student’s home multiple times to make a plan with parents about how to work together and to keep tabs on progress.

There were places for 50 students, drawn from all walks of life across the city. Their families applied and the children had to be examined by the doctor and nurse to be admitted, and to stay enrolled. Students could stay up to three terms to rebuild their weight and improve their health before going back to their neighborhood schools, so the composition of the student body shifted each term.

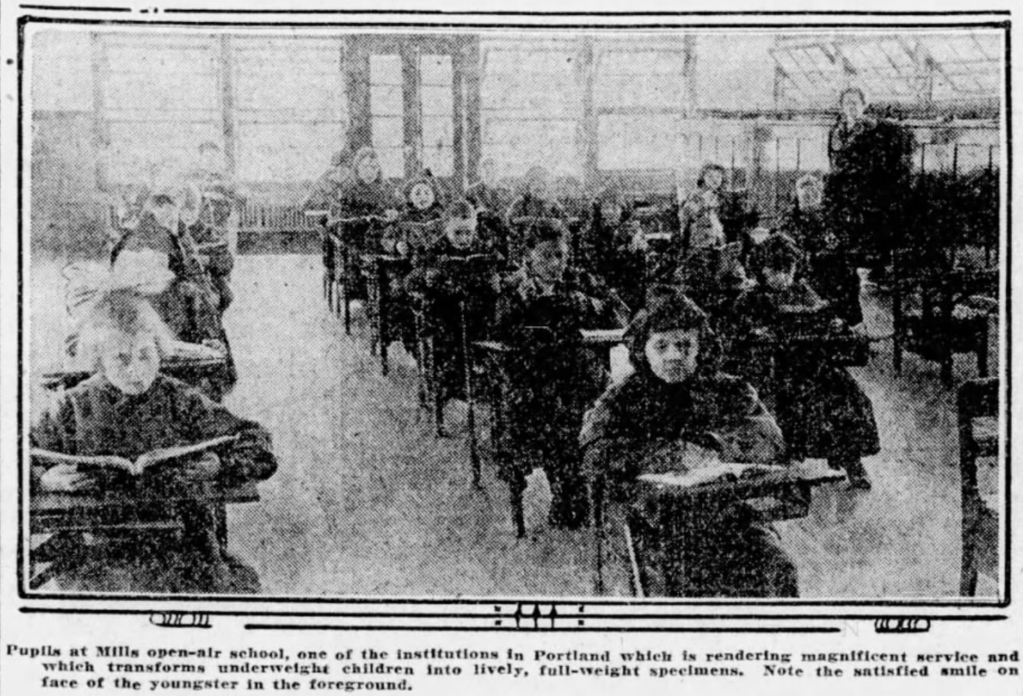

From The Oregonian, February 10, 1931.

In the 1920 school year, 77 total students were in attendance, which means 27 of them were “restored to health” and transferred back to their neighborhood schools, allowing other children to be admitted. The Oregonian in 1920 reported that at one point 15 of the 50 children were “only children,” who theoretically had the undivided attention of their parents–no siblings–a point that Principal Thompson liked to make, perhaps to bolster the fact that unhealthiness was not necessarily related to a lack of resources or attention.

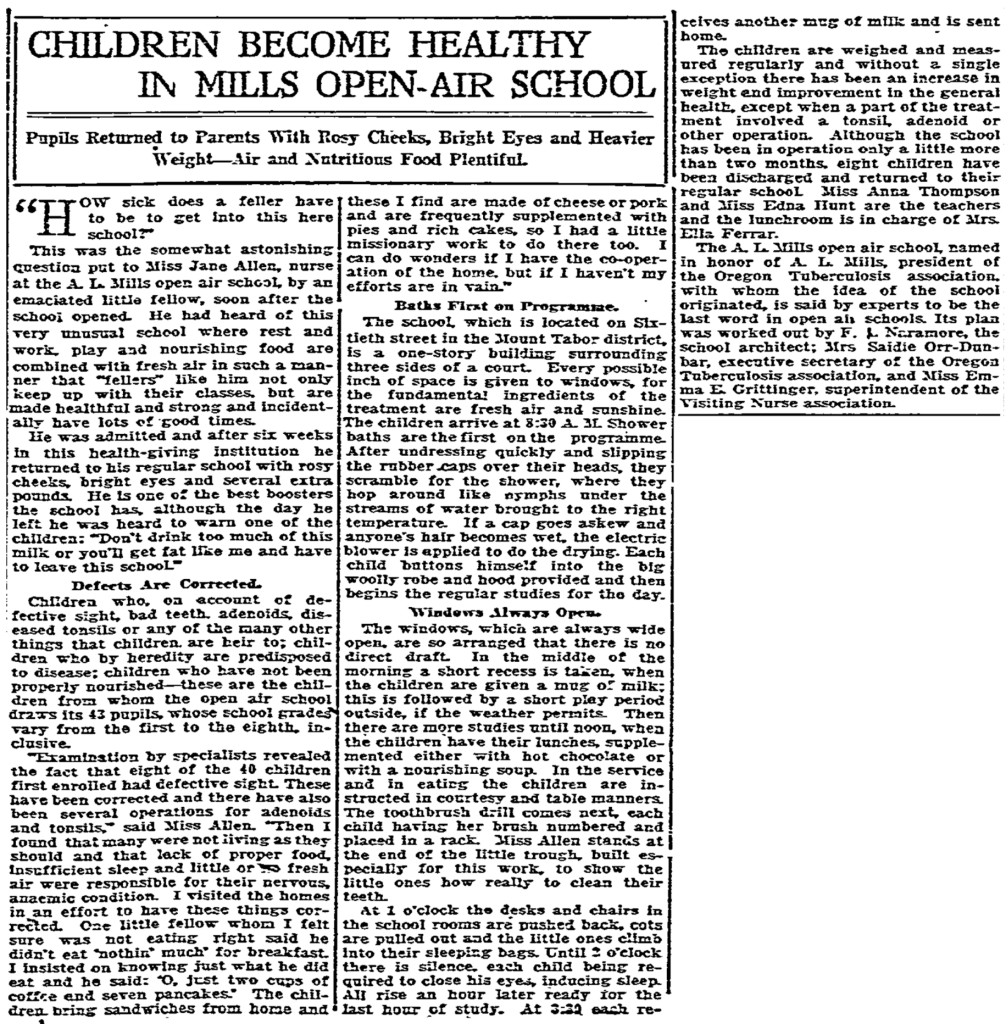

A great description of a day in the life of Open Air ran in The Oregonian on December 10, 1922:

“Shower baths are the first order of the day at 8:00 and during this period once a week the pupils are weighed and inspected for symptoms of physical defects. After baths the pupils put on their sitting robes of heavy blanket material and enter the open window classrooms where they attend their studies until 10:25 at which time half a pint of milk is served in the lunch room to each pupil. This is followed by a period of supervised recreation. When the weather permits games are played on the court or lawn.

“The entire noon hour is given up in preparation for lunch, eating lunch, and preparation for rest. Getting ready for lunch requires washing face and hands, cleaning fingernails, combing hair.

“A copy of the menu of hot dishes for the following week’s lunches is sent home each Friday, so that the mothers will know how to supplement them with the right kind of sandwiches and other foods. For the past week, the menu has been: Monday, hot milk toast; Tuesday, apple tapioca; Wednesday, lamb stew with vegetables; Thursday, hot cocoa; Friday, hot rice”

“After the midday meal, the teeth are brushed and pupils returned to classroom where preparation for rest is made. Cots are spread with warm blankets and after a few vigorous breathing exercises, the rest period begins. At 2:00, the children rise from the cots, faces are washed and hair is combed and studies are resumed until 3:25 when milk is again served and the pupils are dismissed.“

From The Oregonian, December 10, 1922

In cold weather, the children wore heavy robes (pictured above) which were called “Eskimaux suits,” described like this in that same story:

“The brownie coveralls with hood provided by the school to be worn on chilly days are like a fraternity emblem among the pupils and are decidedly popular as their insignia of privileged rank. Sleeping robes are also provided, made of canvas lined with gray woolen blankets that launder well.“

An observation of impact and results were noted in this story from The Oregonian on April 20, 1919, just a few months after the school opened:

From The Oregonian, April 20, 1919

Repurposed to meet current needs

By the late 1940s, the baby boom of Portland’s school-age children brought neighborhood schools to full capacity. With tuberculosis receding as a health threat and the need to make more space, the school board chose to close Open Air, sending students back to their neighborhood schools, and reconfiguring the building as Mt. Tabor Annex, the venue for all kindergarten and first-grade children from Mt. Tabor. A third classroom was built and the converted annex operated as a regular school until 1973.

When the population of school-age children receded, the building was surplussed, ending up in the portfolio of Portland Parks and Recreation, where it was once again repurposed, operating from 1974-1990 as the Mt. Tabor Community Arts Program and Community Theater Workshop.

Budget cuts in the 1990s ended the community arts and theater programs and the building was fallow for several years and on track to be sold to a private school operator, which ended up not happening. In 1994, Parks and Recreation leased the building to the YMCA, which operated it as a daycare for 25 years, until 2019. Operating costs and deferred maintenance ended that chapter just as the pandemic descended, and the old school was once again surplussed, eventually acquired by the Portland Housing Bureau. It’s been vacant since as the Housing Bureau has considered its options.

What’s Next

On each of the recent tours, PHB Capital Projects Manager Kate Piper explained to neighbors that the bureau will soon be deconstructing the old school and salvaging as much of the building material as possible. Redevelopment plans are not yet clear on what happens after that, or when, but removing the existing building from the site is a high priority to manage liability and to set the stage for future development.

This fall’s public tours of the building have helped resurrect and appreciate the stories of Open Air’s past. This time traveler will be going away, but the site has always been a place of change and evolution, meeting the community’s most pressing needs.

No one on the tours questioned the importance of housing, though most couldn’t help but be moved by the stories that have played out there: of Principal Anna Thompson and her team, the children—each on their own pathway to vitality—and the will of a community investing hope and energy in its most vulnerable.

With thanks to colleagues Paul Leistner, President of the Mt. Tabor Neighborhood Association; Kristen Minor, Architectural Historian who completed a detailed survey of the property; and Kate Piper at PHB for recognizing the importance of sharing the Open Air story and connecting with the neighborhood.