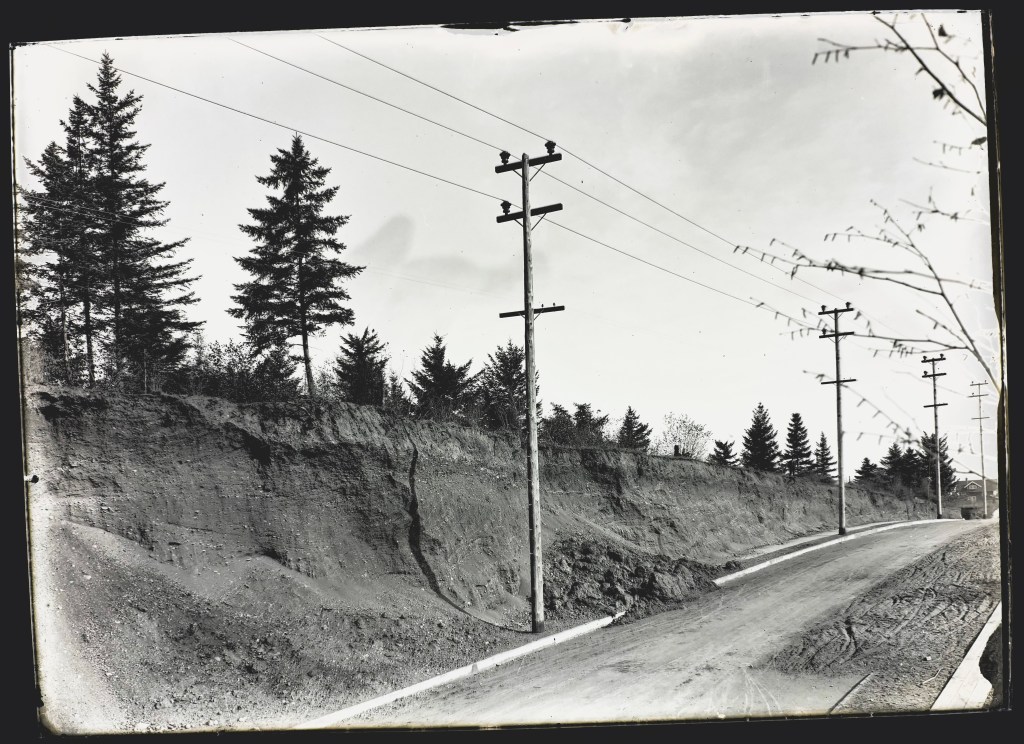

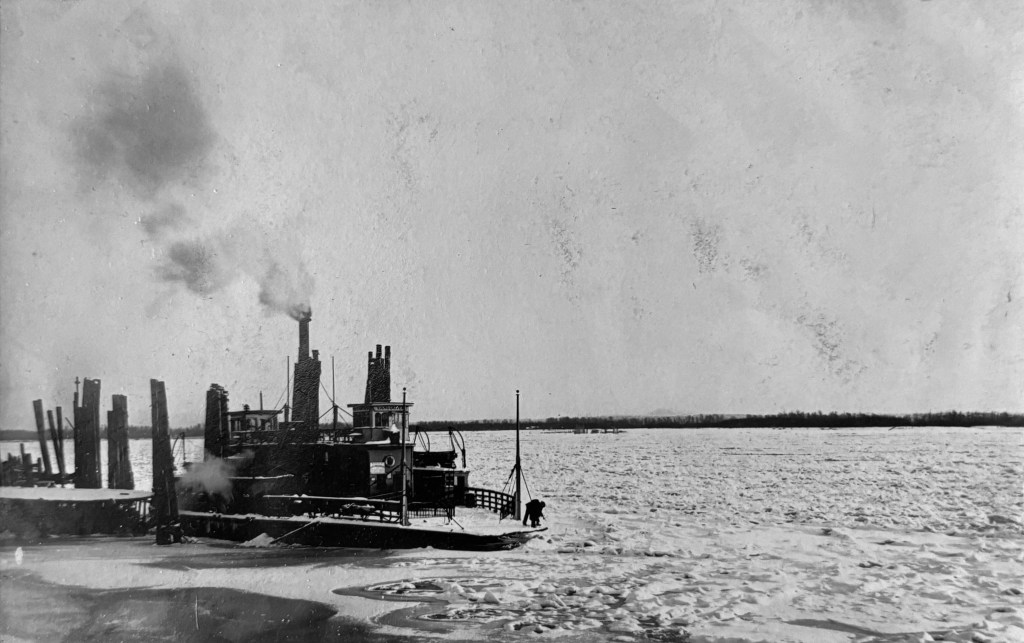

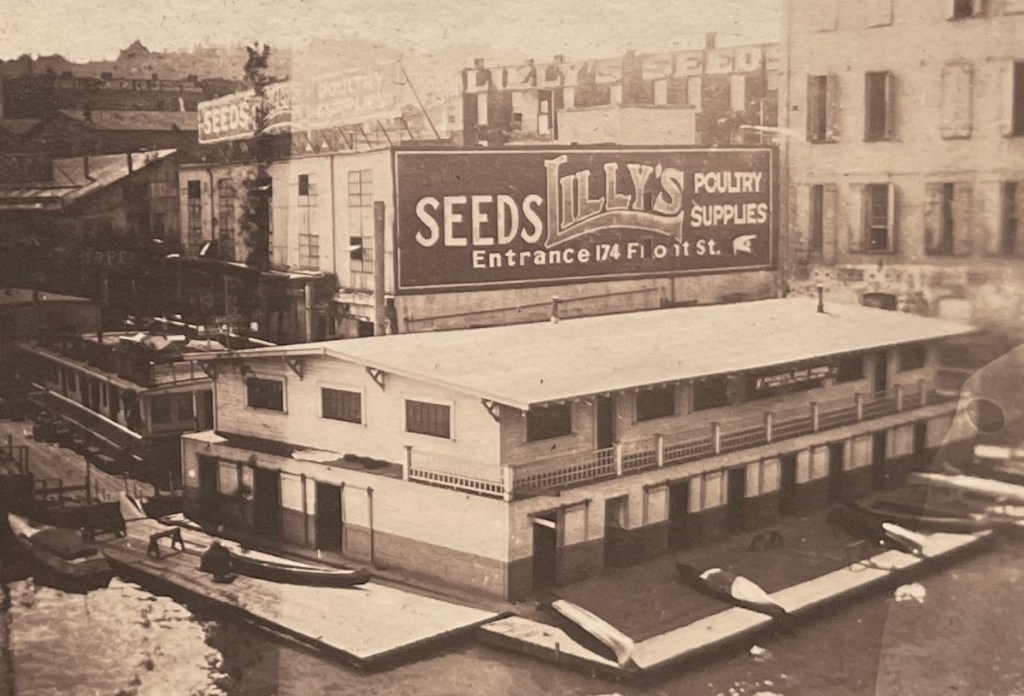

A friendly reader has shared a photograph from her great-grandparents’ photo album and wondered about where it was taken, when, and what it depicts. We love a good photo detective mystery like this, which enables a deep dive back into the landscape of the 1900s. Have a good look at it for detail, and then we’ll discuss:

Courtesy of Phillips Family Archive

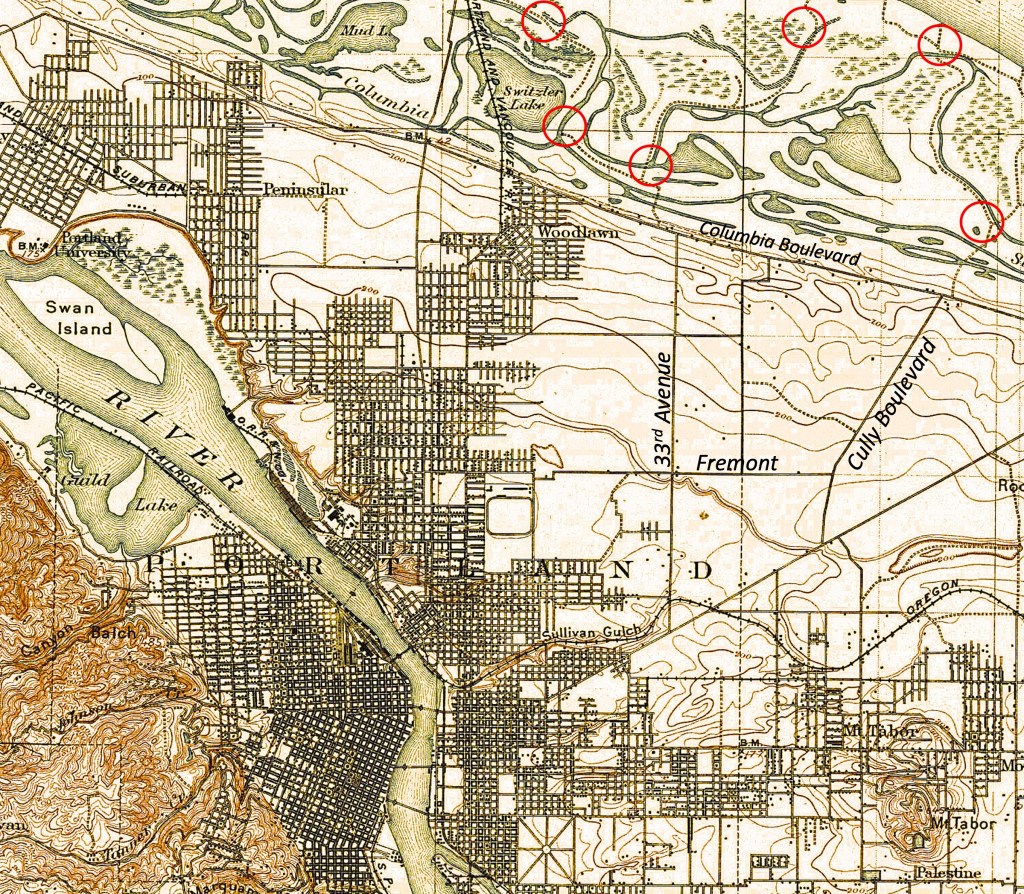

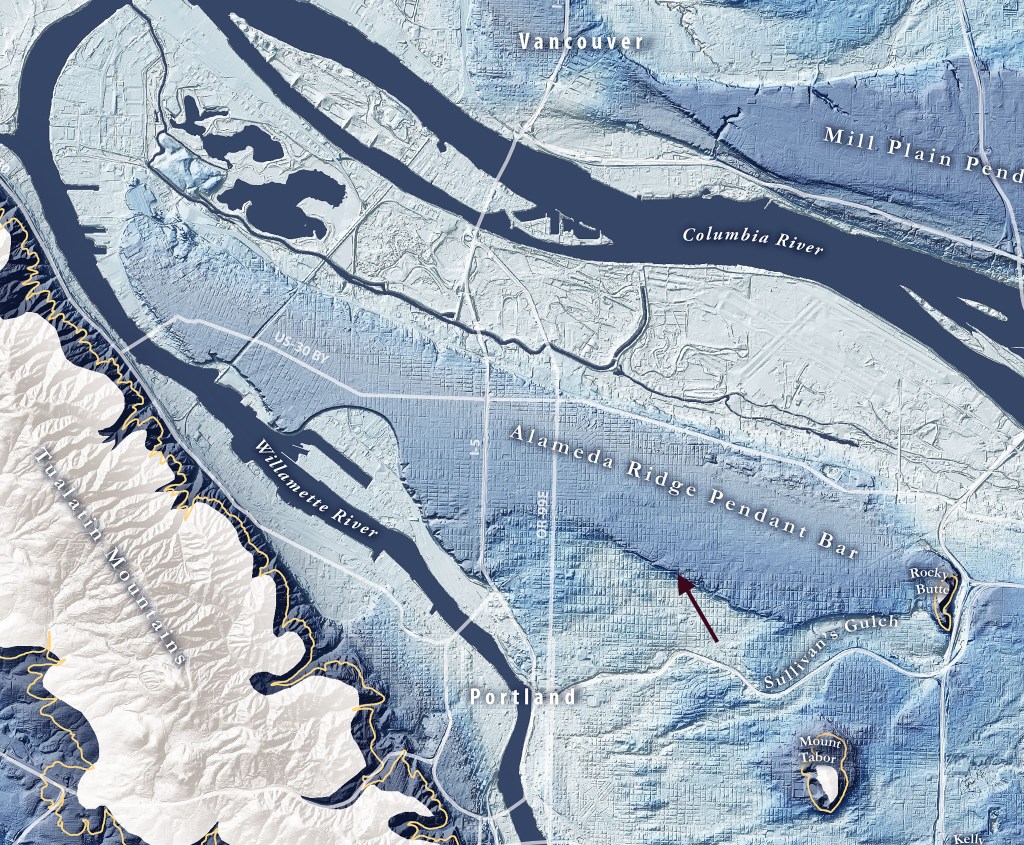

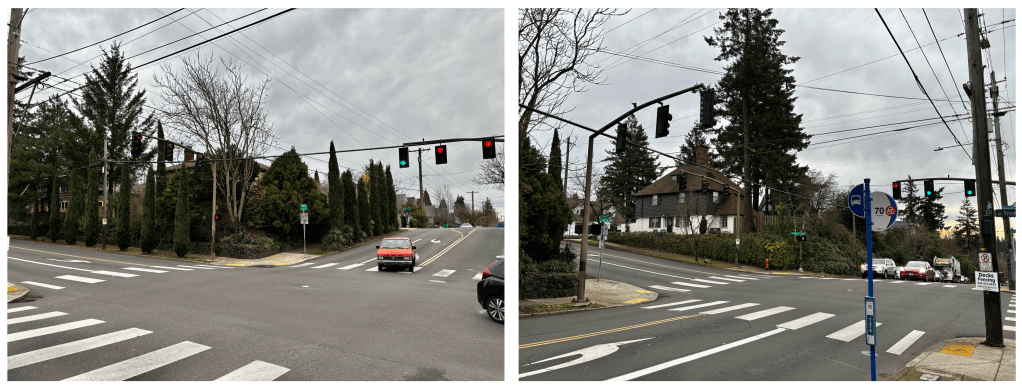

You’re looking north at a newly-completed wooden streetcar and pedestrian trestle bridge over Sullivan’s Gulch (where today’s Banfield / I-84 runs) at about NE 28th Avenue, just south of today’s Hollywood West Fred Meyer. The trestle existed for only a short time–from 1903 to 1908–before pressures from a growing Portland replaced it with a concrete span, which was later echoed by new bridges at NE 21st and then at NE 33rd. Its short lifespan says so much about development about this part of the city during the years immediately after the Lewis and Clark Exposition, which ushered in waves of change for Portland.

But first, the trestle: 800 feet long, an average height over the ground of 35 feet, costing $2,000 to build, including simply a rail line and a narrow sidewalk on the east side of the span. Built between November 1902 and January 1903 by the City & Suburban Railroad, one of the several streetcar companies that served Portland during those years, later subsumed into the Portland Railway Light and Power Company system.

And here’s where it gets interesting: City & Suburban built the trestle under contract to the Doernbecher Manufacturing Company, a furniture factory, which was Portland’s largest private employer at the time and which operated a sprawling five-acre factory site at the bottom of the gulch just beneath the trestle. Thousands of workers made the trip into and out of the gulch each day and having a means of easy access was helpful for the company, which had opened the factory just a few years earlier in 1899. If you haven’t heard about the factory, you can read more and see photos in this piece, which was the second installment of a series we’ve written on the history of Sullivan’s Gulch. Today’s giant U-Store storage complex is the skeleton of what once was Doernbecher Manufacturing.

City & Suburban Railroad operated the East Ankeny Line, which terminated in the streetcar barns that once stood near NE 28th and Couch, about a mile due south. For the executives at Doernbecher, it was an obvious proposition to pay the railroad to extend its line north straight up 28th, build the trestle and two prominent stairways down, so workers could come and go conveniently. Meanwhile, City & Suburban was also eyeing service to the neighborhoods taking shape to the north of the gulch, and the possibility of a loop with the existing streetcar service that ran up Broadway into Irvington and later Alameda.

And so it was in August 1902 when construction of the line extension began:

From The Oregon Journal, August 19, 1902

By November, the extension was in and grading was underway at the lip of the gulch to prepare for the trestle. Wood was being stockpiled for construction:

From The Oregonian, November 12, 1902

Trestle construction began in earnest in December and was completed in January. Later that year, the East Ankeny Line was extended a bit farther north to an end-of-the-line stop at NE 28th and Halsey. The envisioned loop with the Broadway Streetcar never materialized.

The trestle enabled a broader infrastructure that began to serve middle Northeast Portland. In November 1903, an 8-inch water main was secured to the wooden structure carrying public water for the first time into this part of the city:

From The Oregonian, November 5, 1903

In 1907, following the Lewis and Clark Exposition and with home construction and residential land speculation fever running high, residents of the area began to lobby for a wider multi-use crossing of the gulch in this area. The trestle was replaced in 1909 by construction of a concrete viaduct.

The story of sleuthing the photograph is interesting too:

- We knew the Doernbecher story in this location, and could see the “Doernbecher Manufacturing Company” painted on the side of the building in the photo. The alignment of the Doernbecher building, slightly angled to the crossing, is still evident today in what may well be the very same building.

- The homes pictured at the edge of the gulch, several of which are still standing today along NE Wasco and Multnomah streets, provide a tell-tale indicator this view looks north.

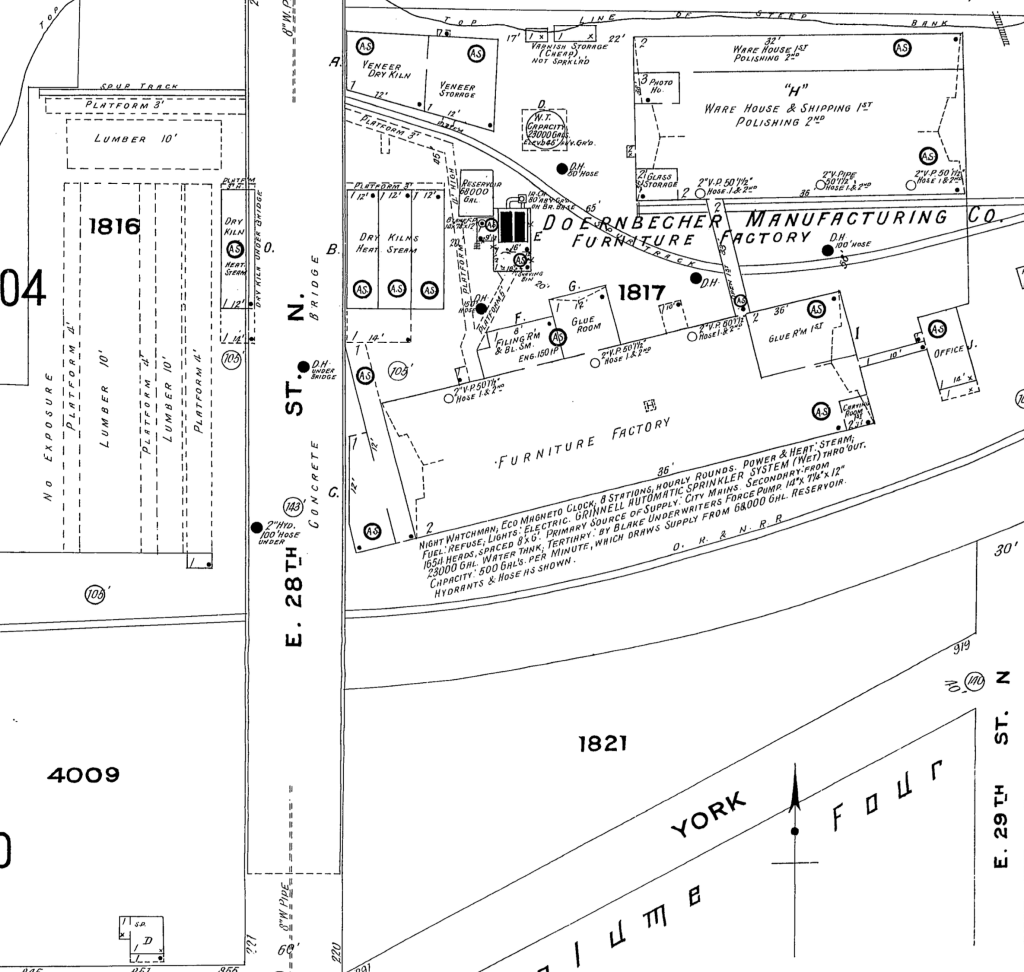

- The Sanborn Fire Insurance Map from 1909 also helped, lining up nicely with the Doernbecher lumberyard seen in the old photo through the rungs of the trestle railing and mentioned in the news stories. Knowing the buildings were to the right (upgulch) and the lumber yard was to the left (downgulch) also confirmed direction of the view.

Detail from 1909 Sanborn Fire Insurance map.

- The Sanborn also shows the Oregon Railway and Navigation mainline (much later the Union Pacific) which travels through the gulch and was the reason Doernbecher cited the factory there in the first place. The bowler-hatted gentlemen on the trestle walkway are probably looking down as a freight train passed by underneath. Look carefully and you can see the electric and telegraph lines that followed the tracks running perpendicular to the trestle in the mid-ground. The 1909 Sanborn shows the concrete bridge which replaced the trestle.

Do you have old photos you’re trying to make sense of? We’re always glad to help.