Sleuthing old photos to determine location, context and insights is a favorite thing to do; the Photo Detective category here on the blog is testament.

But sometimes, the biggest mystery is just finding the old photo.

Such was the case recently when a reader wrote seeking an assist in locating a photograph of a house fixed in childhood memory from the 1950s: his grandparents’ home on the bluff above Ross Island, torn down more than 50 years ago to make room for McLoughlin Boulevard. No known photos of the house had survived.

But in his memory, a version of the house was still there. Burnished over the years and important because it was a house that contained the full arc of life for people he cared about who were also gone. Maybe by having a photo of the house, he could call them to mind, and consider his own experience there as a small person.

When researching houses for clients, we’re always looking for old photos, but there is no single source or easy way to do this. In Portland, it’s worth following your address back through old copies of The Oregonian and the Oregon Journal to see if there is a photo from an advertisement or some random mention over the years. You’d be surprised, it does happen.

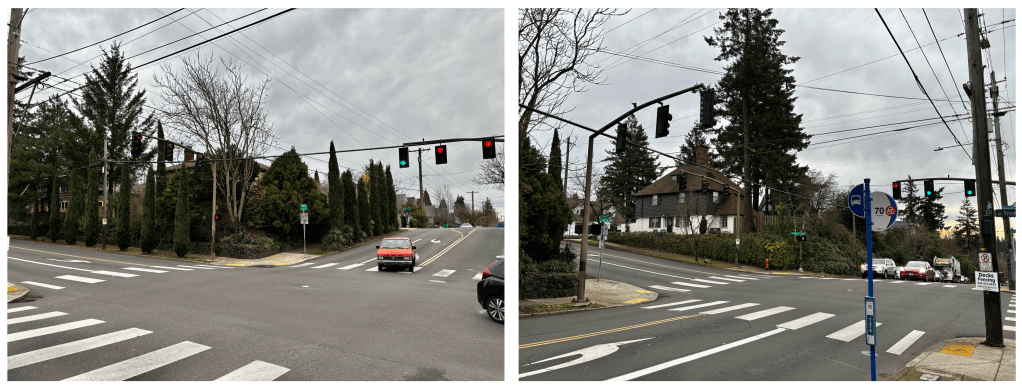

Another potential source is Portland City Archives, which has a deep collection of public works, traffic study, zoning study and “stub toe” photos that might include an incidental catch of a place or building of interest somewhere in the background. You can use the search tool called efiles to search by intersection or street.

The stub toe photos are an interesting subset, documenting sidewalk tripping hazards for liability reasons and occasionally catching a house of interest in the background.

The Oregon Historical Society Library has collections of neighborhood photos that are always worth looking through: you might find something you didn’t even know you were looking for.

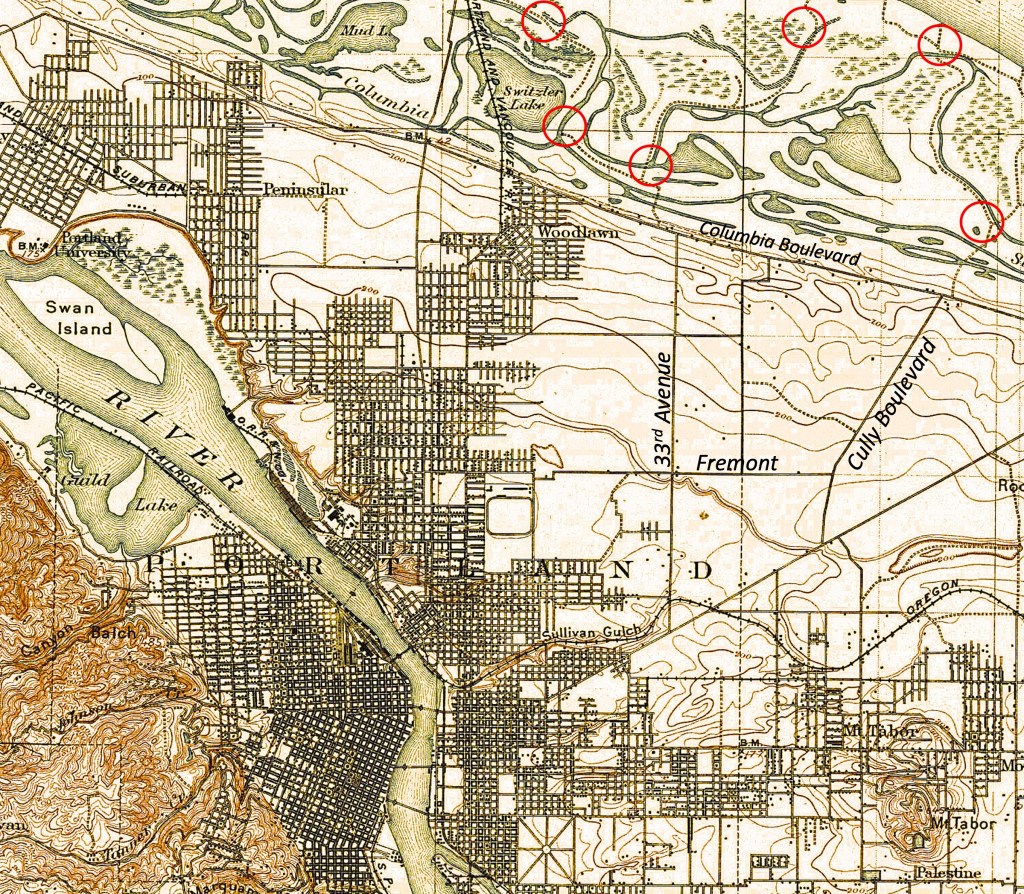

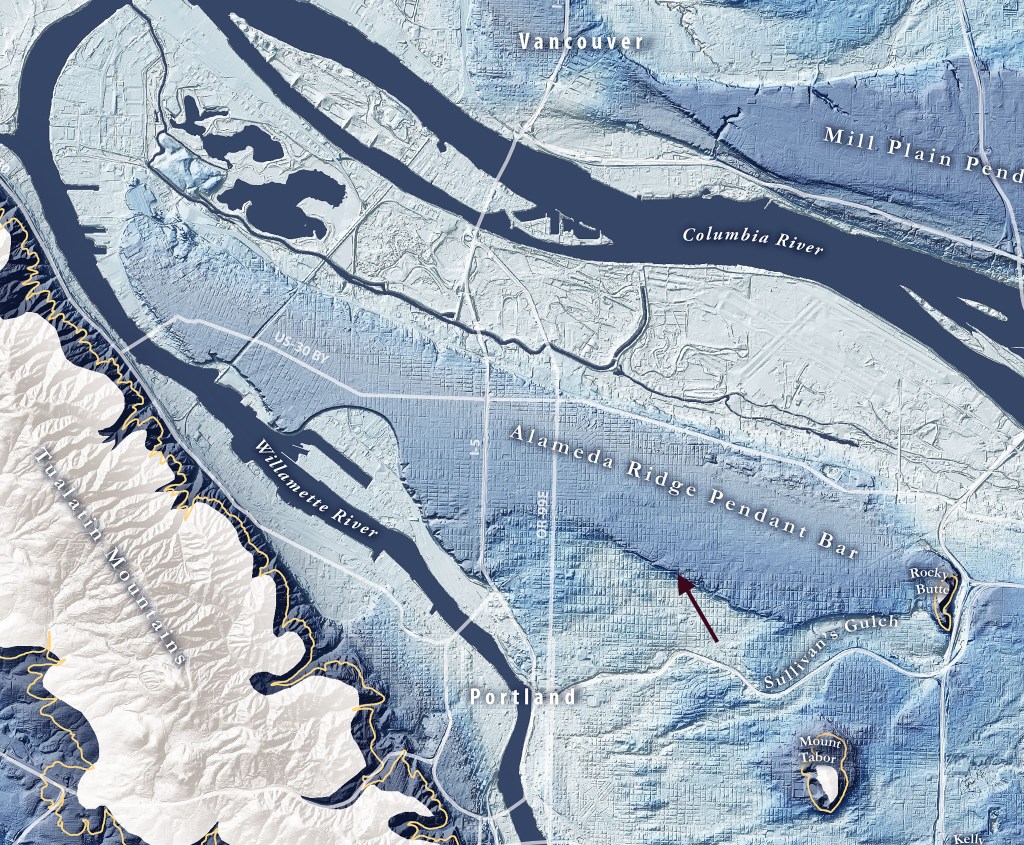

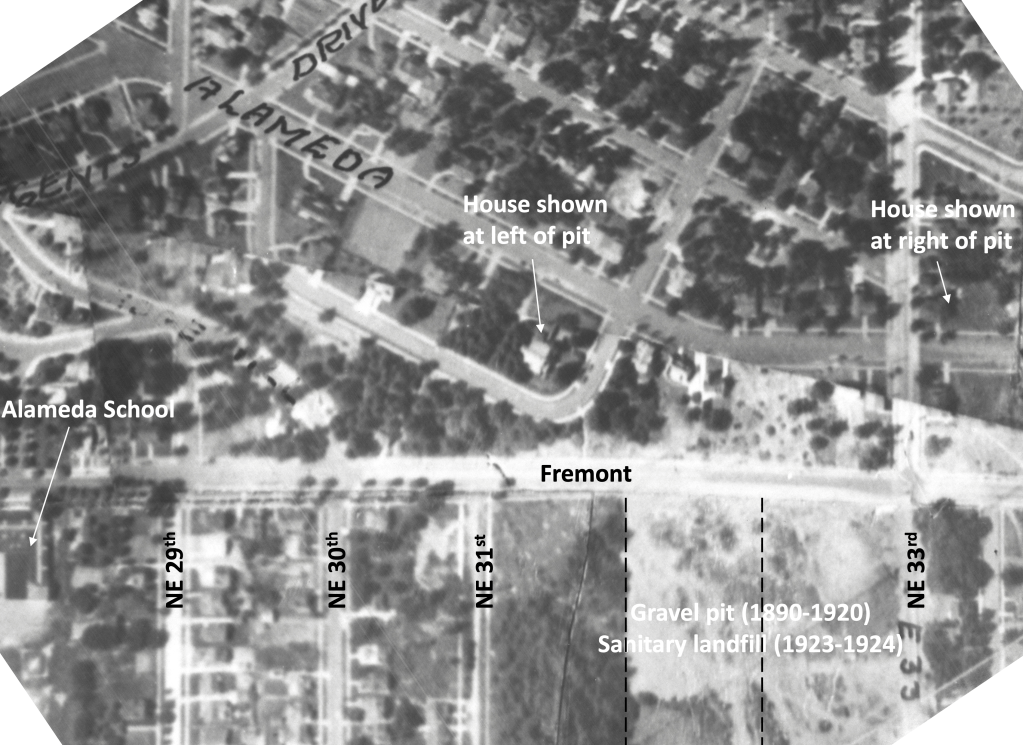

There are aerial photos too, some of which are available through City Archives, and others through the University of Oregon Library’s Aerial Photography Collection. Dating back to 1925, these images are mostly low resolution and grainy, but good enough to help address larger-scale mysteries. Examining the same place from the air every 5-10 years back to 1925 is fascinating and always humbling to see all we’ve missed and don’t know about a place.

An advanced aerial photo function within the indispensable research tool Portland Maps allows a year-by-year look back to 2006 and then in some cases back to 1948. And of course there is Google Streetview.

But the best sources with the best pictures are always private collections, as in family photo albums and attic shoe boxes of photos, which are also the most challenging and rewarding to find. But that’s another blog post.

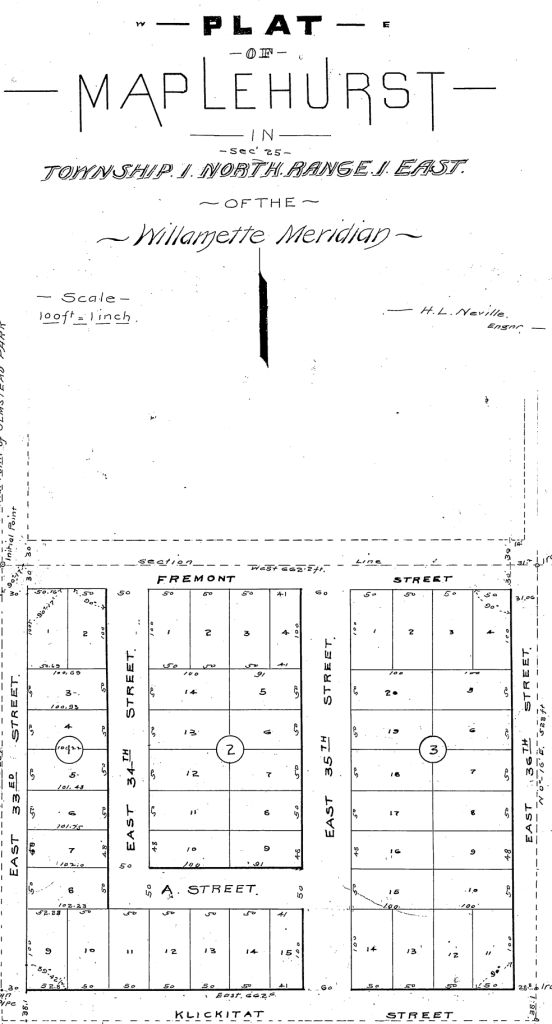

Long before construction of McLoughlin Boulevard, the remembered house on the bluff had a Grand Avenue address, and stood on the east side of the street at the corner of Haig. Back in 1912, Grand Avenue was never intended to be a major thoroughfare connecting downtown and the central eastside with outer southeast Portland. Think: quiet, meandering neighborhood street.

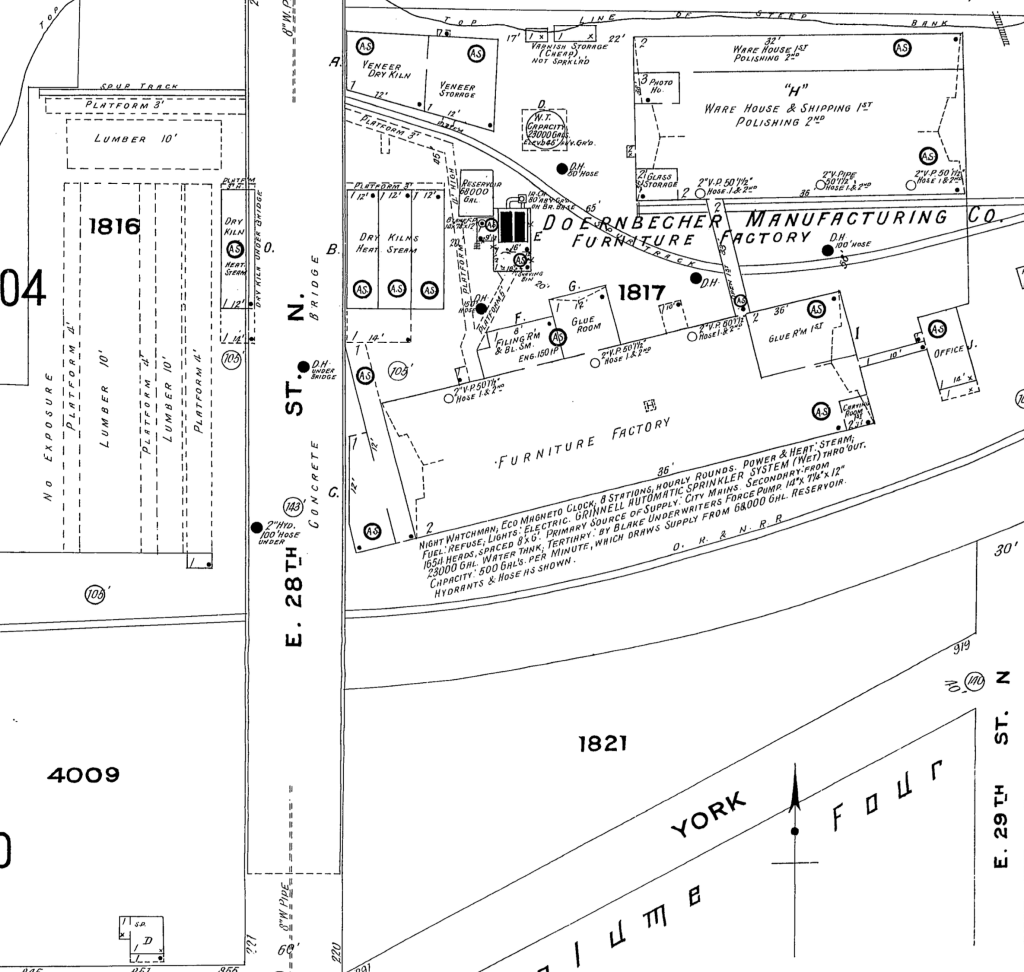

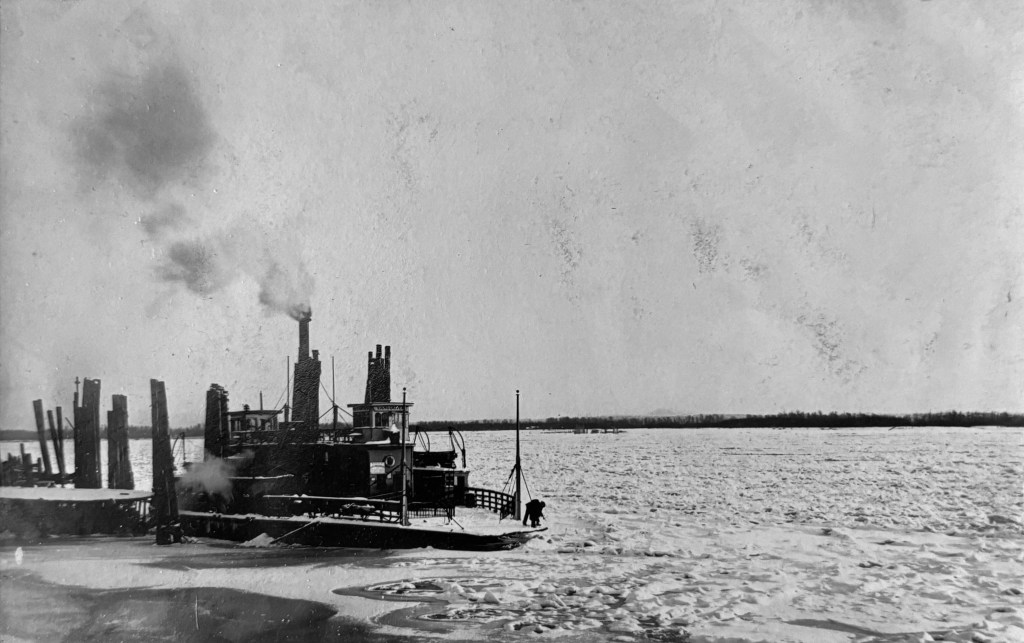

Early on in the search, we used aerial photos and Sanborn maps to understand how Grand Avenue has changed. It once followed a slow, looping route along the high bluff to take in the views of the Willamette River to the west, calling to mind the way in which SE Sellwood Boulevard edges high above Oaks Bottom today. In the river just downslope from the house was the north end of Ross Island, with views straight at Bundy’s Baths and Windemuth.

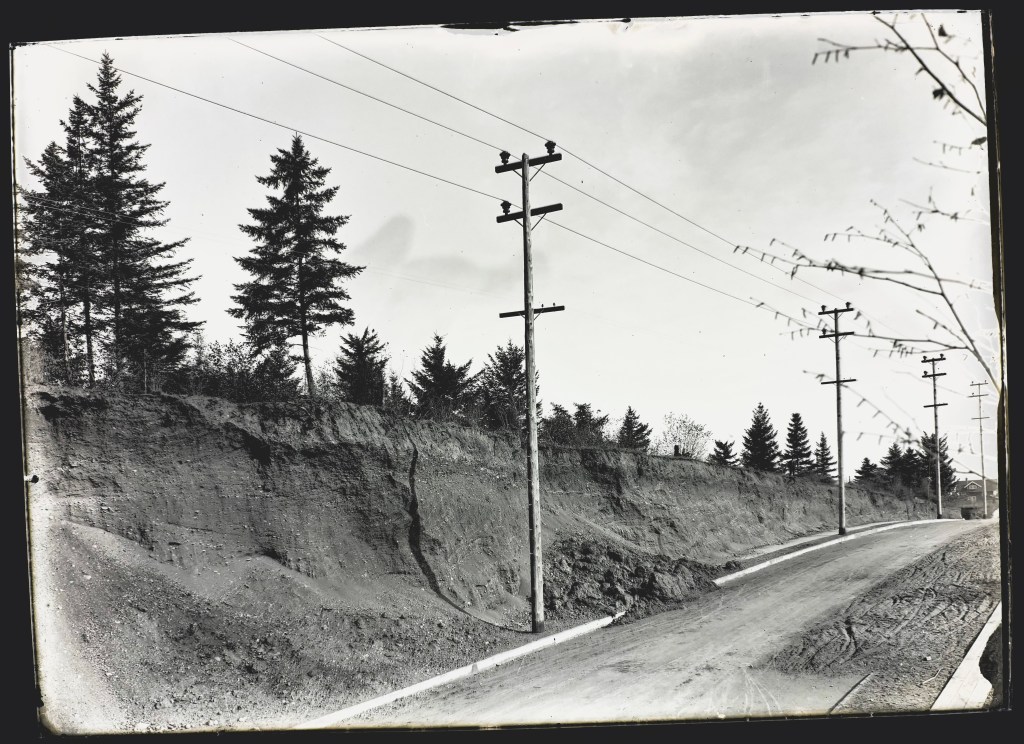

It wasn’t until the late 1930s and early 1940s that Grand Avenue was widened and McLoughlin Boulevard first opened. Given growth in all parts of southeast Portland and northern Clackamas County—and the rise of the automobile in everyday life—traffic volumes began to increase and congestion followed. The Oregon Highway Commission was under pressure to “fix” the problem. By the mid 1960s, traffic engineers with the State Highway Division knew that widening of McLoughlin to six lanes—which had become Pacific Highway East, Route 99E—would be necessary, dooming the former neighborhood street.

By then, the remembered family in the remembered house were gone and the sense of that former neighborhood as a quiet place to look out over the river below was quickly slipping from living memory.

That’s when the studies began: land use studies, traffic flow studies, engineering studies. Surveyors out on the ground taking measurements, and–fortunately for us–taking pictures. And that’s where we were able to pull this house back to life from one sunny Wednesday afternoon in June 1965, through the lens of a traffic engineer. That’s it there on the right, the Craftsman bungalow, dormer facing west. Click in for a closer look.

How does the photo compare with the memory? Maybe an unfair question since how does memory ever compare with anything, but we wanted to know. Certain things were familiar.

But just having the photo created a perch from which other memories and imaginings and questions could now rise. And for an old house researcher like us, it felt like finding the precious needle in the overwhelming haystack.