Planning for spring and summer season guided history walks is underway: I’ll be leading four walks for the Architectural Heritage Center through Northeast Portland neighborhoods. Registration (and fee) with AHC is required for these, and they’ll send you meet-up details as well.

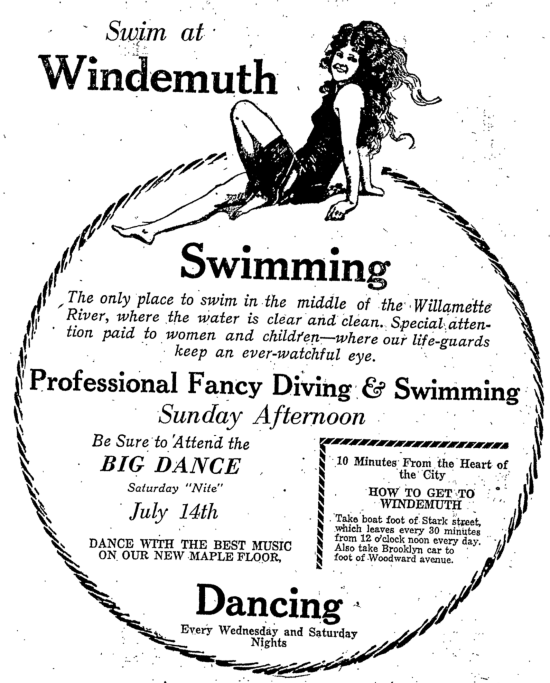

Coming right up on Friday, March 6th at 5:00, I’m doing a free program at the Oregon City Library looking at Portland’s historic love affair with the Willamette River: Windemuth and Bundy’s: Where Portland Played in the River. The OC Library requests registration (which is free!).

Just an FYI, I’m always glad to consider leading walks and programs for groups interested in exploring local history. Let’s talk if you’re interested. Meanwhile, have a look at the calendar:

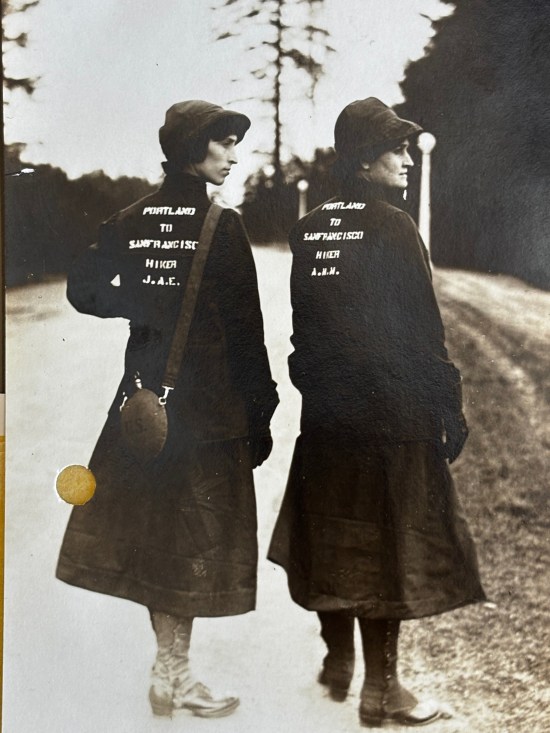

We won’t be walking to California like this Portland mother-daughter duo from 1915 who always inspire us. But we will be walking! Join the fun.

Saturday, May 30, 2026 at 10:00 am – Beaumont Neighborhood History Walk

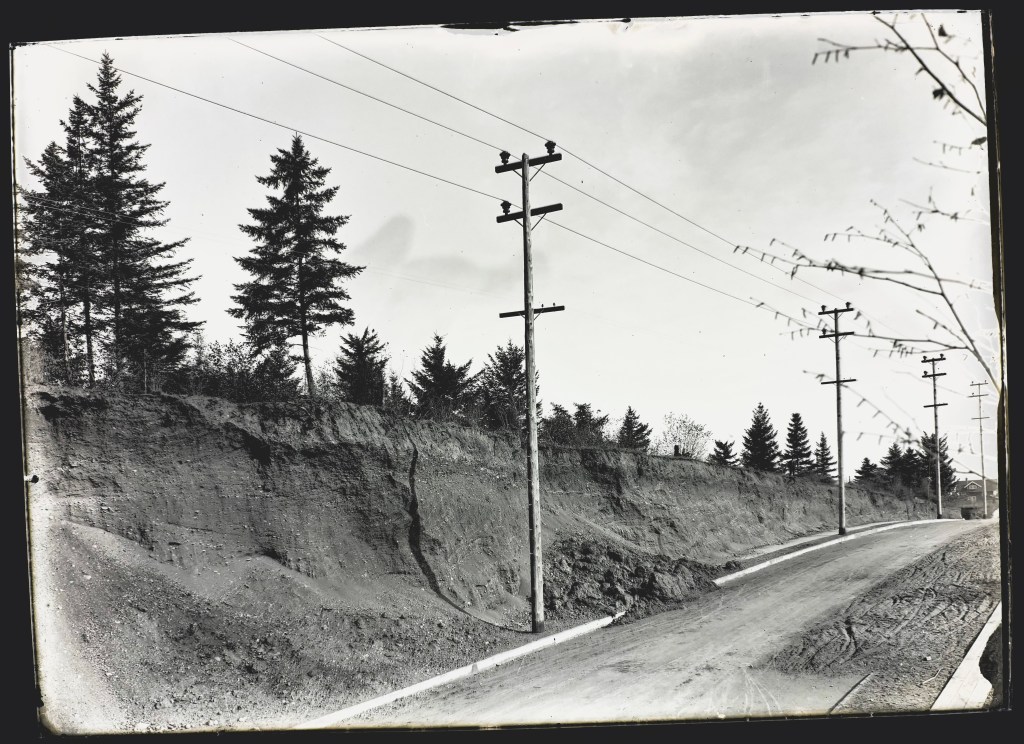

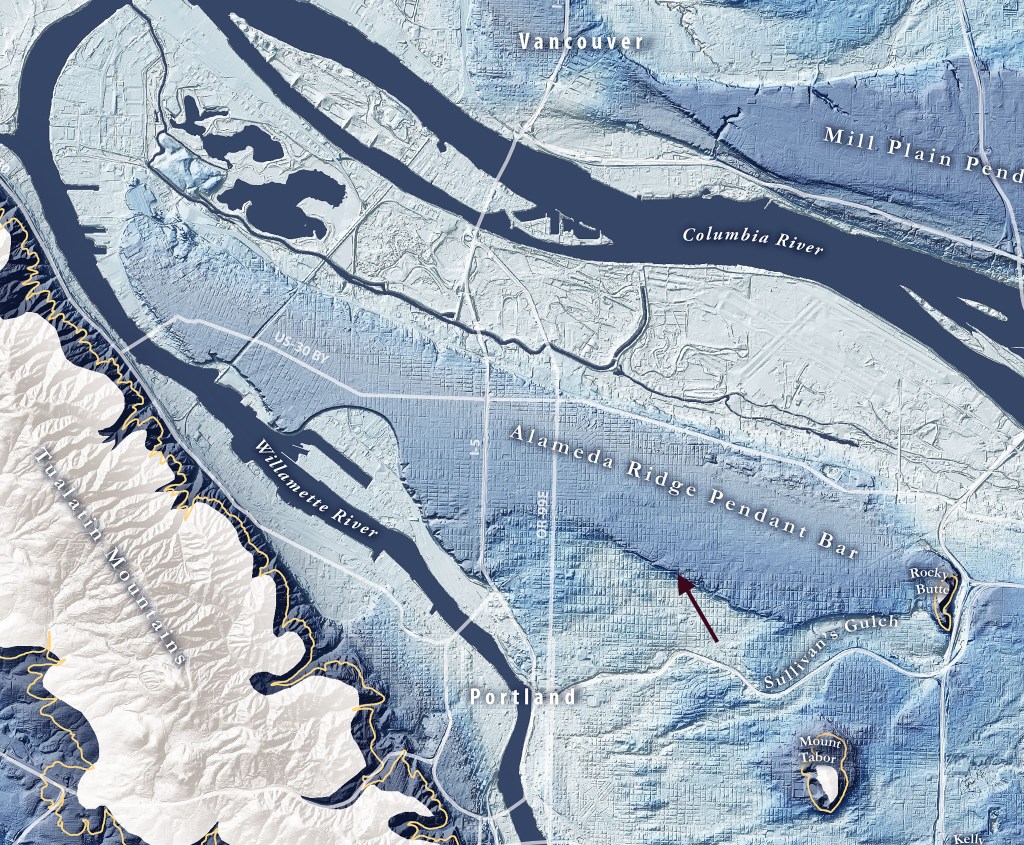

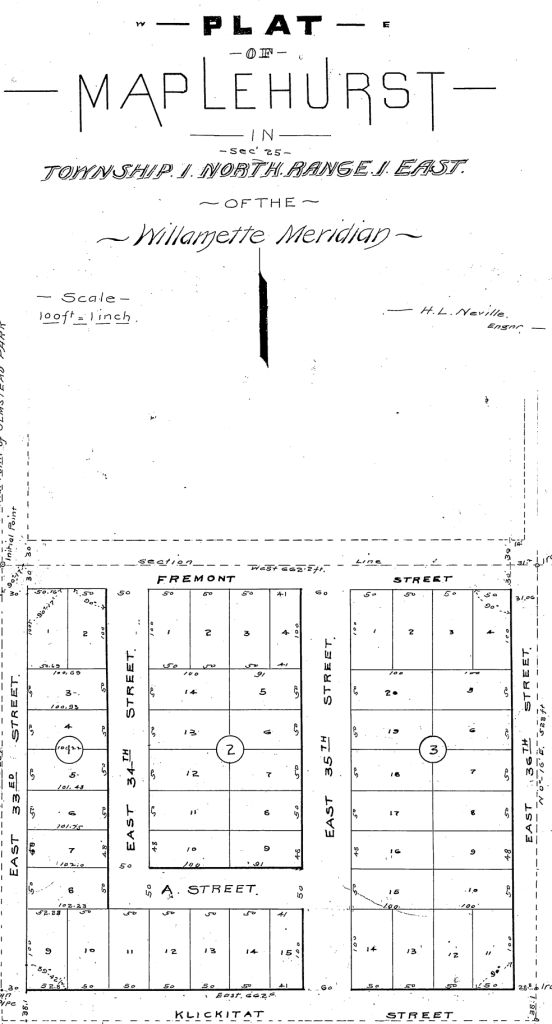

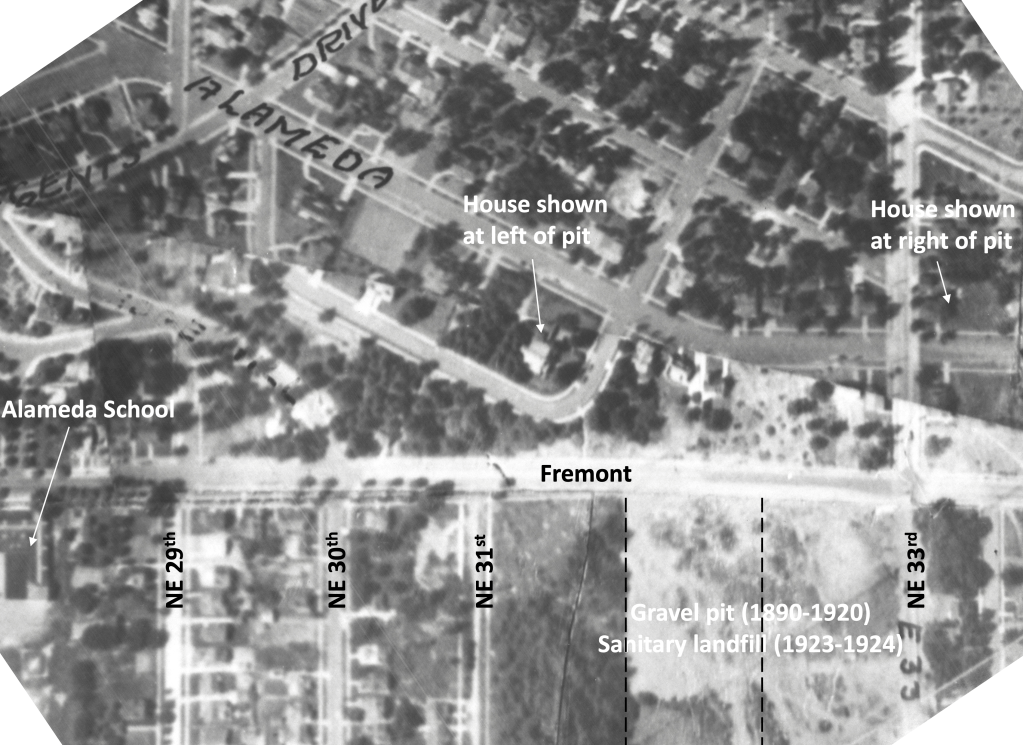

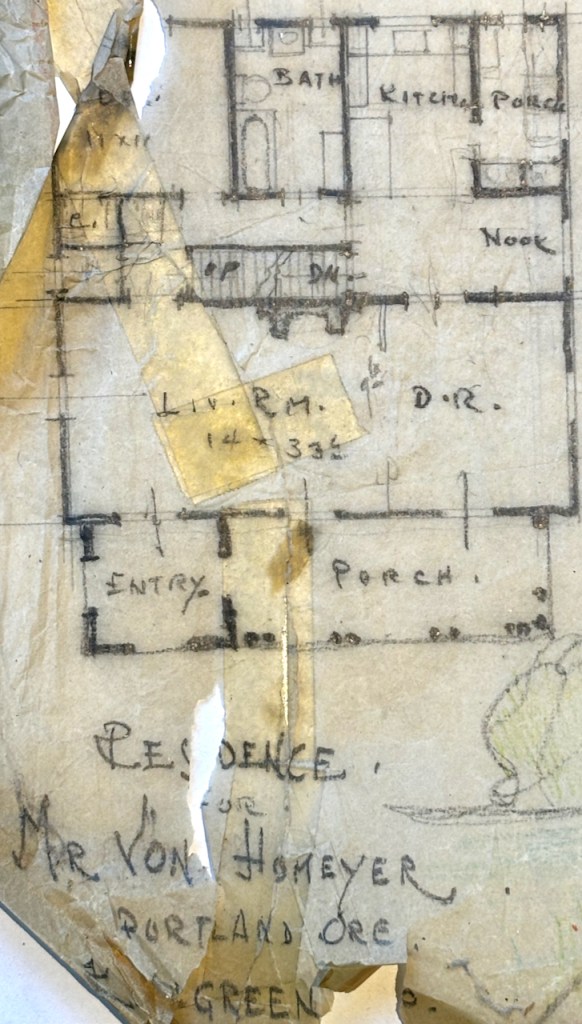

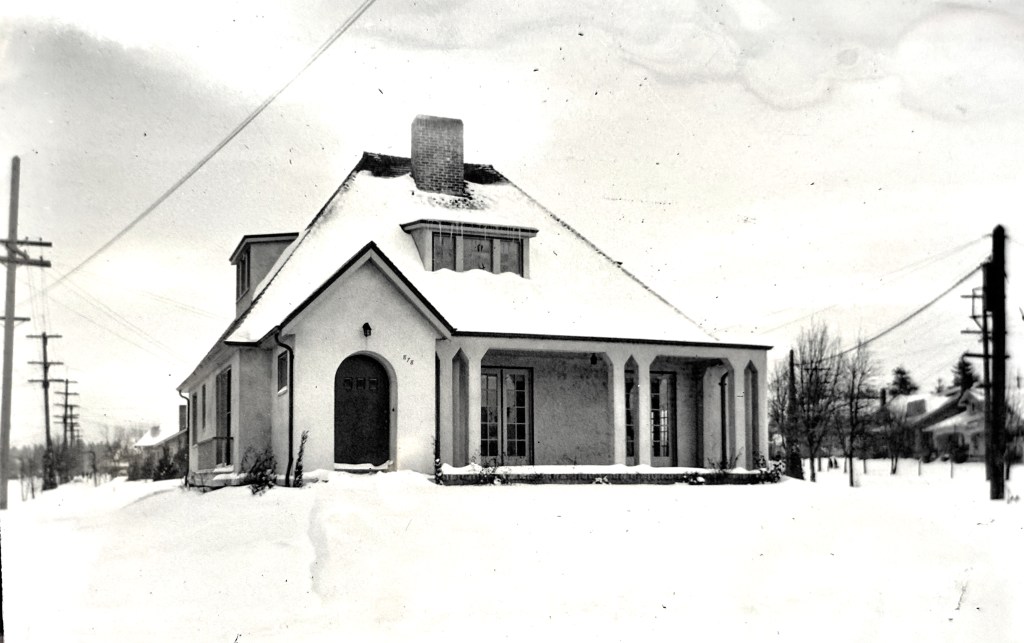

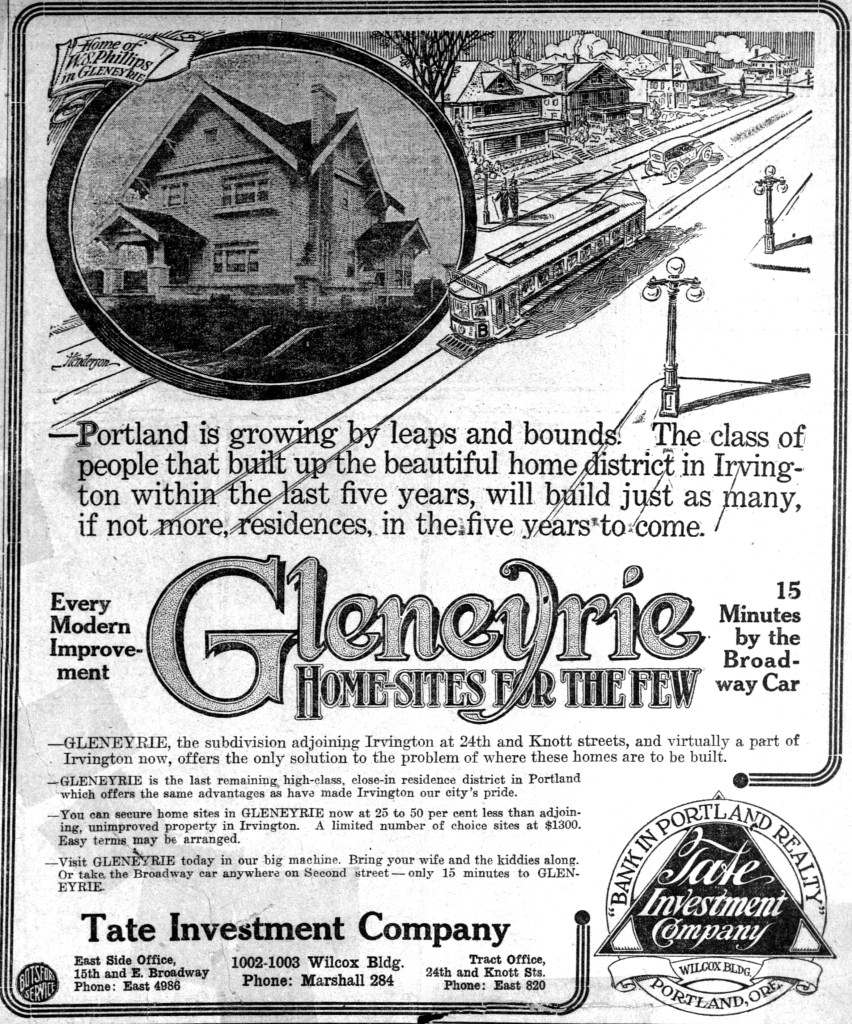

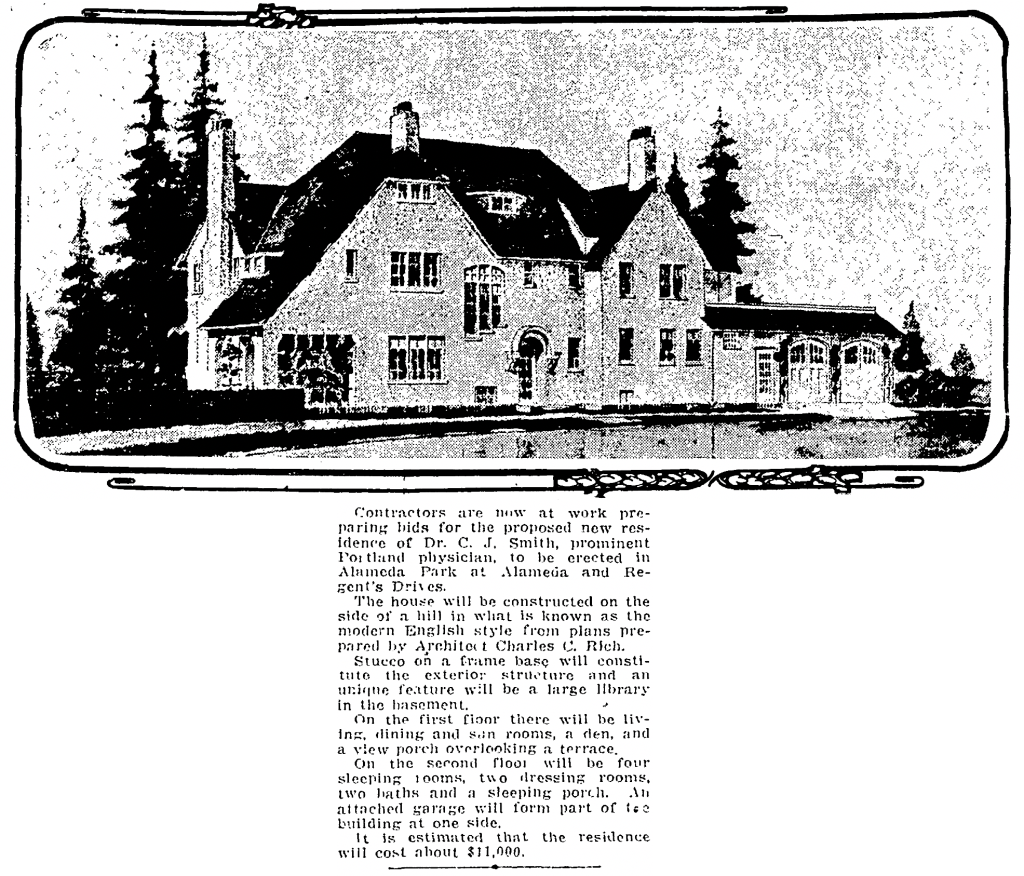

One of Northeast Portland’s signature planned neighborhoods, Beaumont—“the beautiful mountain”—was platted in 1910, had its own named school, business district and streetcar route, and was home to one of Portland’s wealthiest and most powerful families that built a compound for its seven children. Join me for a walk along Alameda Ridge that ties these stories together and explores 116 years of neighborhood development. Registration link.

Saturday, June 6, 2026 at 10:00 am —Wilshire Neighborhood History Walk

Northeast Portland’s Wilshire neighborhood has long been tied to its neighbor Beaumont. But its history and development followed a very different trajectory. On this Saturday morning stroll, we’ll walk through a planned neighborhood that was never developed, explore multiple attempts to create Wilshire Park (which almost failed!), and line up with then-and-now photo points that show dairy pasture and forest stands at the heart of today’s residential neighborhood. Registration link.

Tuesday. June 30, 2026 at 10:00 am —Alameda Neighborhood History Walk

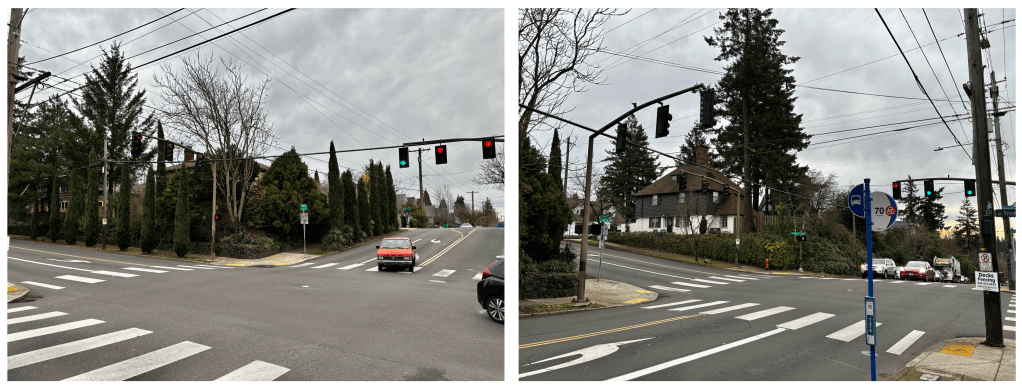

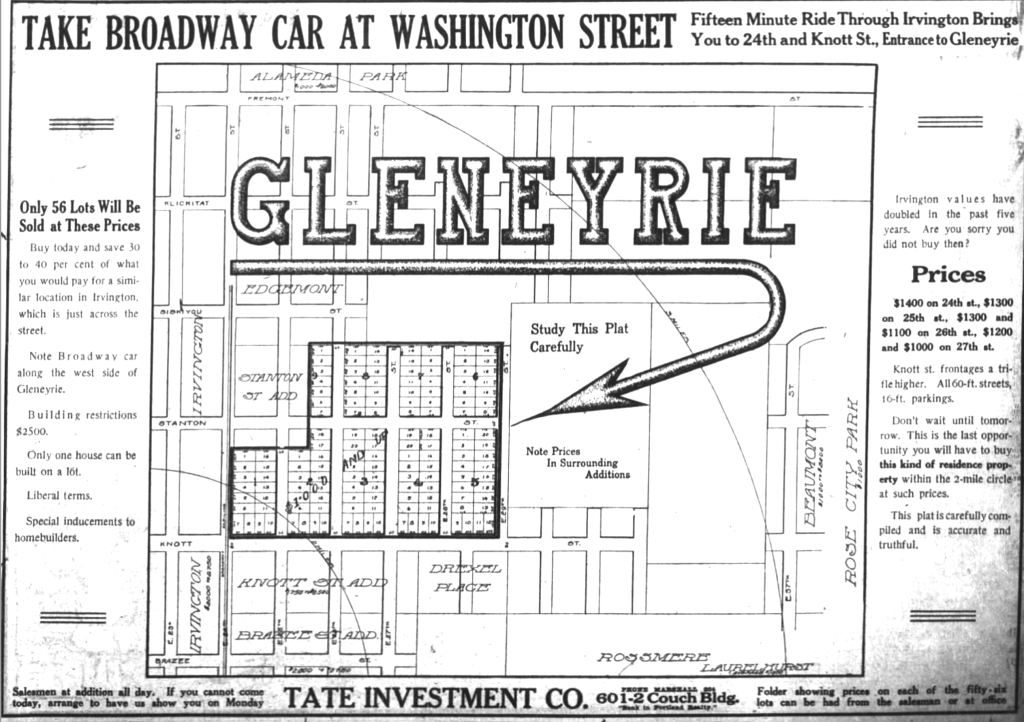

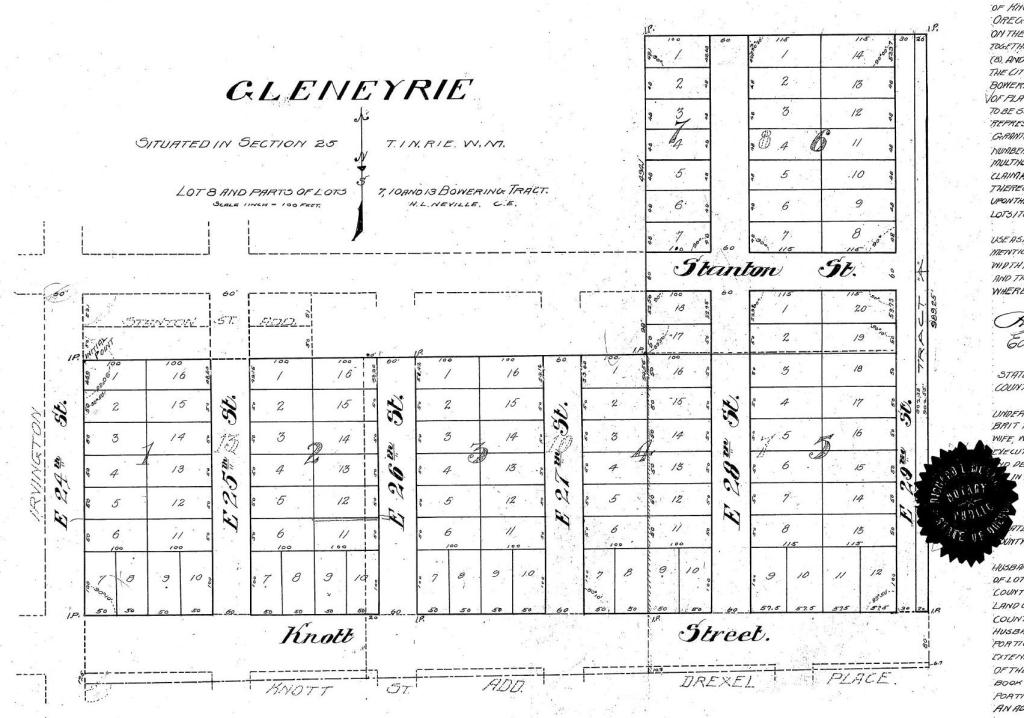

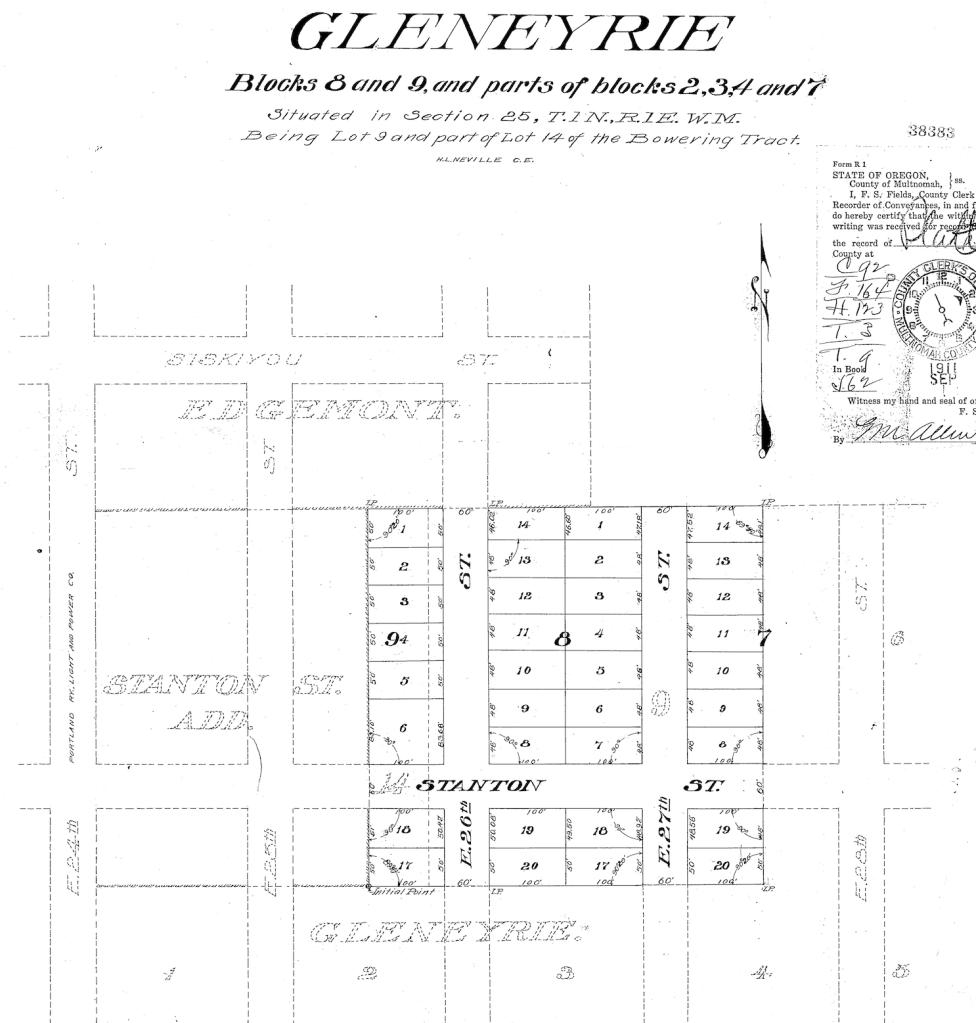

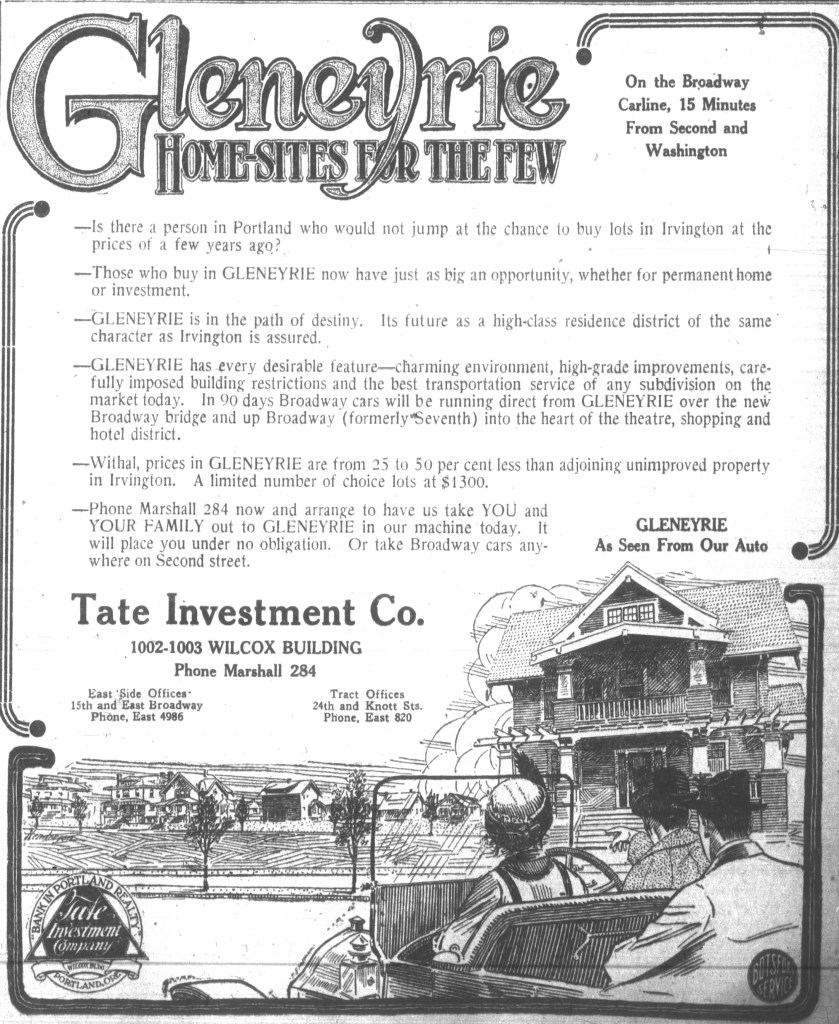

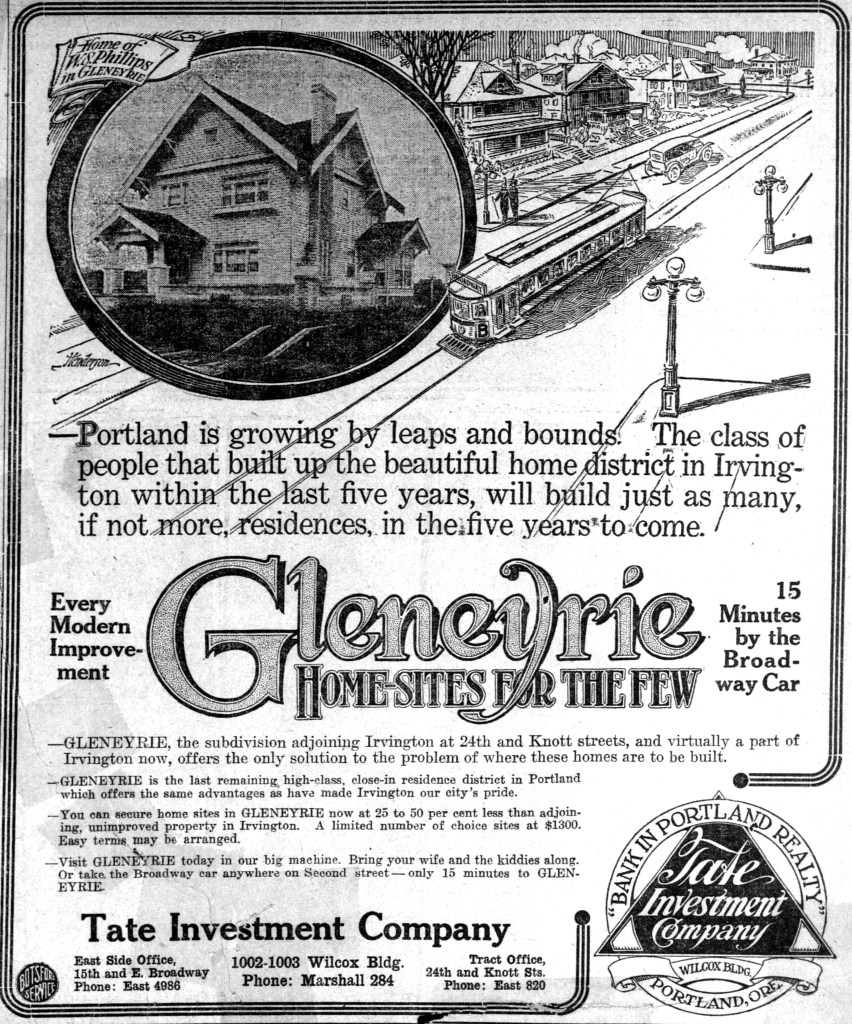

This Tuesday morning walk will explore the connections between past and present that shape the Alameda neighborhood we know today. This 90-minute stroll will cover just over a mile with multiple stops focusing on pre-development conditions, planning and construction of the neighborhood, the Broadway Streetcar, architectural house styles, and stories of local interest. Most of this walk is on flat terrain other than a gradual stretch that ascends the Alameda Ridge. Registration link.

Tuesday, July 14, 2026 at 10:00 am —Vernon Neighborhood History Walk

Come explore the layers of history in the Vernon neighborhood, from development of Alberta Park, to the fall and rise of neighborhood schools, to patterns of redlining from the 1930s-1950s, the presence of dairies, a much-loved old synagogue, a popular streetcar and a street full of small businesses. We’ll walk back in time to understand the how legacies of the past have shaped the neighborhood of today. Registration link.