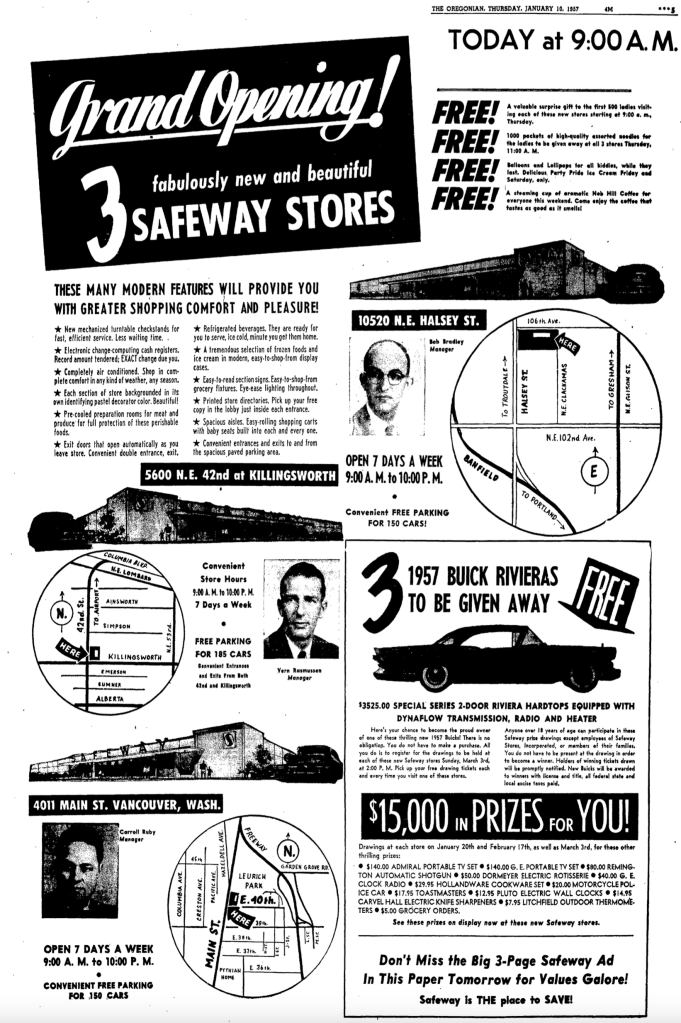

If you’ve spent time in the Alameda neighborhood, you’ve probably seen this house and wondered about its story:

The von Homeyer house, NE 24th and Mason, May 2024. Brothers Karl and Hans lived their entire lives in the house and on summer evenings greeted neighbors and watched the world go by from their front porch chairs.

It’s the steep-roofed, run-down yellow house on the prow of the intersection where NE 24th, Mason and Dunckley streets come together, built and occupied for all of its life—since 1926—by a single family: the von Homeyers.

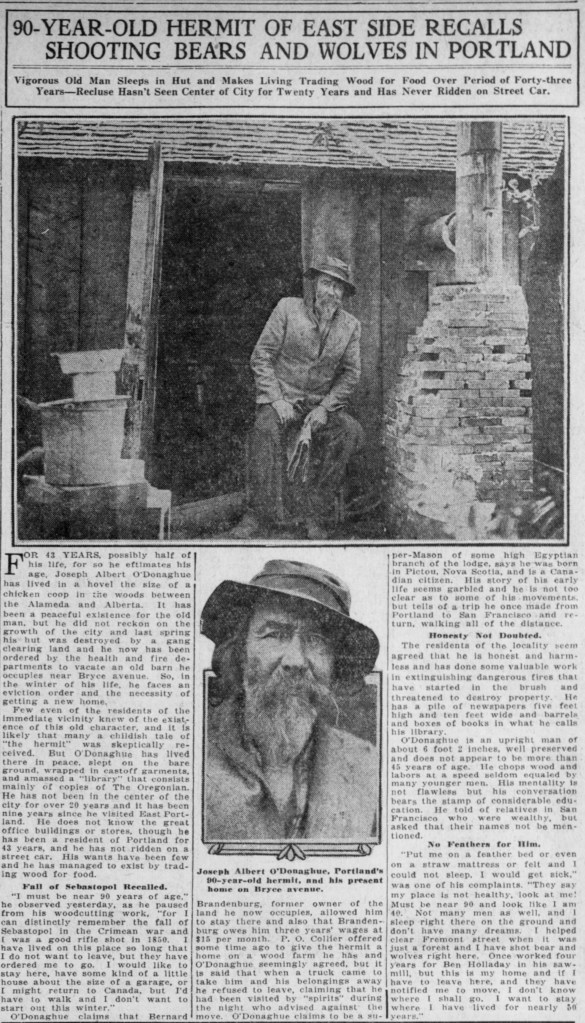

Older neighbors might remember the brothers—Hans and Karl—who on summer afternoons and evenings would sit on the front porch and visit with dog-walkers, runners, and anyone willing to say hello. We’ve lived in the neighborhood since the late 1980s and always enjoyed a brief chat with the idiosyncratic brothers who had tinfoil on their windows and seven cars in the backyard, but were always friendly and ready to visit or share a laugh.

Karl and Hans Homeyer, in the 1990s

Hans and Karl never married and lived in the house all their lives. Hans died in 2002. Younger brother Karl is now in his 90s and moved into a Portland care facility last year. The home was built in 1926 by their parents, Hans W.S. von Homeyer, who died in 1969, and Frances Westhoff von Homeyer, who died in 1990.

Earlier this year, after being unoccupied (but not empty) for almost a year, the house was purchased as-is by across-the-street neighbors Jaylen and Michael Schmitt, who knew “the boys” and couldn’t bear to see the place torn down, which is what most people probably thought was going to happen because it is in such tough shape. Inside, the house was jam packed with decades of papers and other items piled high leaving little room to walk or sit.

“We’ve always been worried that it would be demolished and replaced by something that wouldn’t be right for his iconic piece of property, ” says Michael, recalling the classic bungalow that was torn down in 2017 a few blocks east at NE 30th and Skidmore and replaced by a duplex, despite neighbors’ concerns. And another bungalow on NE Mason that was torn down last summer and replaced by a much larger house.

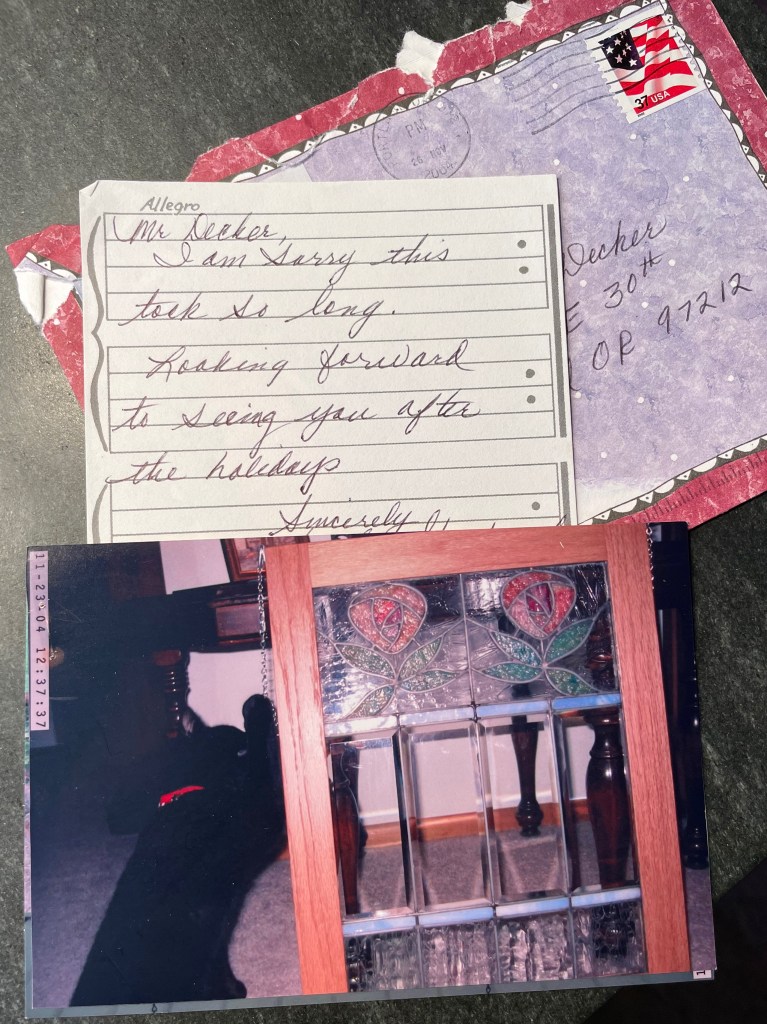

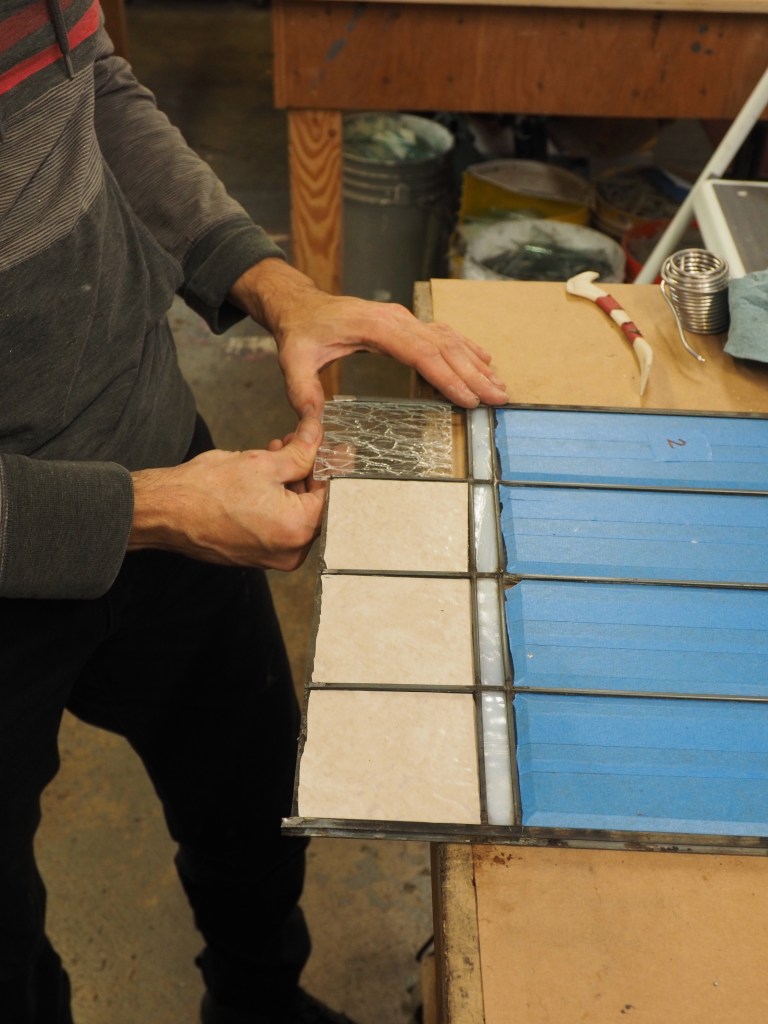

With help from a small army of friends and neighbors, the Schmitts have been sorting through boxes, bags, and containers that were stacked from floor to ceiling holding everything from video games to ammunition; from 1940s-era ice delivery receipts to vintage clothing. Michael reached out to me for help sorting, contextualizing and organizing hundreds of photographs and personal papers that tell the story of the families and the original design and construction of the house. It’s been a fascinating assignment.

This spring, I’m helping the Schmitts create an archive that documents the life of the house and its family that can travel forward in time, and that offers a narrative about the last 100 years here.

In future posts, we’ll write more about that, and about how we’ve been curating the photo archive. The insights are as amazing as the photos and go off on many different and fascinating tangents. We’ll also explore the design, construction and history of this house, its family, and the interesting role they played in the early neighborhood.

But for now, things are beginning to happen and the neighborhood will begin to see activity around the house. The Schmitts are hosting an estate sale starting today through this weekend and the list of items for sale is pretty remarkable: fabrics and sewing patterns from the 1940s-1960s; lot of tools; a pinball machine, magazines galore and an amazing selection of auto racing trophies from the 1960s. Even if you are not in the market for a vintage steamer chest or sewing machine, the estate sale is an opportunity to see this time capsule of a house.

This weekend’s sale is an early step toward restoring and adapting the house for the future. An architect is working with the Schmitts on subtle changes that add bedrooms and bathrooms, and update the kitchen which is still in original and very worn 1926 condition. Other less visible but crucial changes, like updates to all major building systems, are in the plans too.

“Whatever we do, we want to be in keeping with the spirit of the original design and with a sense of the neighborhood,” Michael says, recognizing the real estate market of today is much different than 100 years ago. To make it a marketable property going forward, they’ll be adding a bedroom and bathroom in the basement and also on the first or second floor. The steep rooflines and the shed-roof dormers on the second floor make fitting another bedroom up there a little tricky. More analysis and imagination required before they can answer that question.

One design change we’re looking forward to seeing: the signature west front columns and French doors–walled up long ago–finally set free, a kind of time travel return to the architect’s original vision.

NE 24th and Mason, early 1930s. Photo courtesy of the von Homeyer Collection.

For now as work gets rolling with this spring’s estate sale, it’s enough to acknowledge the significant amount of work required to bring this house back to life, the many stories this place has to tell, and the vision of neighbors committed to restoring and adapting a unique property for its second century.