Alberta Park marks its 100th year in 2017, originally leased from a local property owner and then condemned by the city in 1921 to provide needed park and open space for the growing neighborhood.

Alberta Park 1929. Courtesy City of Portland Archives.

Like many areas of our city, northeast Portland’s neighborhoods evolved from Homestead Act land claims, where settlers bought or received rights from the federal government to develop open land for farms and homes. The recorded real estate transaction history of the Alberta Park area begins in 1866 when Mexican-American War veteran Harry McEntire used his Military Bounty land exchange certificate to acquire the property bounded by today’s Ainsworth, Killingsworth, 19th Avenue and 22nd Avenue: what we know today as Alberta Park.

As developers began to lay out streets and neighborhoods for the area beginning in the early 1880s, the property changed hands. Chinese business leader, landowner and entrepreneur Moy Back Hin, referred to by The Oregonian at the time as “Portland’s first millionaire” acquired the property, along with other real estate he owned downtown and on the eastside. Hin was frequently in the news for his real estate dealings and as a leader of Portland’s vibrant Chinese community: he served as Chinese Consulate General to Portland.

In 1910, Hin called on the city to follow through with plans to open Killingsworth Avenue between Union Avenue and NE 42nd (a $150,000 project for which the funds had not yet been identified) saying that as soon as the street was opened he would begin to build houses on his land.

During those years, eastside home construction was exploding: commercial development booming along Alberta Street; a vibrant home building business across nearby neighborhoods; a major streetcar line—packed with commuters—serving these new communities carved out of the fields and forests northeast of downtown.

Through its community clubs (of which there were many), locals began calling for development of parks. Influential Catholic priest The Reverend James H. Black—who went on to lead southeast Portland’s St. Francis Parish for many years–appeared before the Portland Parks Board to encourage the board to purchase land for a park in the Alberta area before real estate values jumped.

Minutes of the meeting show the chairman informed Father Black that “at present there are no funds on hand to purchase park property, and suggested that he write a communication to the Board incorporating his ideas in regard to the proposed Alberta Street Park property.”

In November 1912, locals petitioned the city, saying the more than 14,000 new residents of the area deserved a safe place to recreate and noting that nearly all the available lots for playground space had already been built over.

From The Oregonian, November 3, 1912

By 1917, the last remaining unplatted stretch of land in the area was the 17 acres bounded by 19th, 22nd, Killingsworth and Ainsworth, owned by Moy Back Hin. While Hin did eventually planned to develop the area for homes, he agreed to lease the property to the city starting in 1917 to serve as a park. Almost immediately, baseball diamonds, a clubhouse, walking paths and restrooms were built on the leased property.

In 1920, with the parcel in popular public use (and Killingsworth Avenue now open and paved between Union and NE 42nd), Hin offered to sell it to the city for $65,000, which was refused. The city responded with an offer to buy it for $39,333, which Hin refused. City Council responded on March 23, 1921 with an ordinance condemning the property and ordering it taken over by the city. After a jury trial, Hin was paid $32,000 and the property was taken over as a “public necessity.”

In 1924, the city passed an ordinance naming the parcel Alberta Park, though it was frequently referred to as Vernon Park as well. Hundreds of newspaper references to the park—and to the robust City League baseball schedule that occupied the new baseball diamond and sometimes drew more than 1,000 spectators—randomly used both names. Use of the Vernon Park name faded by the 1940s.

Investment immediately followed the city acquisition. A 1927 inventory of the property identified the following improvements:

1 wooden field house, built 1922 for $500 (heaters to be installed in 1927)

Two comfort stations (including a tool room) built in 1926 for $5,000

Sewer and water connections

One shelter

1925 plantings: $1,096

1926 plantings: $223.47

27 lights, cost $3,469.21

70 hose bibs and four automatic sprinklers

One large baseball field with backstop

One small baseball field with backstop

One wading pool, built in 1927 for $719

4 sets of horseshoe courts with steel frames and covers

2 sand courts ($100 and $108.72)

1 handball court

2 tennis courts ($1,722.58 and $2,055.86)

1 flag pole

Alberta Park “comfort station” and lamps date to 1926.

Hundreds of references in newspapers of the day called the new parcel as Vernon Park and sometimes used the two names interchangeably in the same story, but on April 9, 1924 the city passed an ordinance officially naming it Alberta Park. The official name change didn’t seem to stick: newspaper references to Vernon Park show up well into the 1940s.

An annual summer community picnic tradition connected neighbors of all ages and included a parade, games, the naming of a local queen, dancing and a lantern parade after dark.

From The Oregonian, August 16, 1924.

In October 1927, the Portland School District tried to acquire the southern five acres of the park as a location for the “new” Vernon School being planned to replace the original Vernon School south of Alberta Street that had become too small for the growing neighborhood. The city attorney, referencing the 1921 condemnation order and its intent that the property was acquired specifically for a park, refused to budge, protecting the park we know today. The school district scurried to find a site, selecting the current school location on the south side of Killingsworth Avenue across from the park.

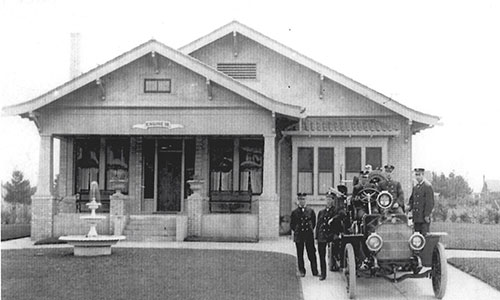

In the 1950s, despite a fractious encounter with the neighborhood that included references to the 1927 decision by the city attorney not to subdivide the park, the city made a different decision and did allow use of the southwest corner of the park for construction of Fire Station 14.

Aside from the new fire station, not much changed in Alberta Park until the 1970s, when a comprehensive planning effort and citizen survey recognized a changing pattern of use. The 1972 report found:

“Alberta Park has remained relatively unchanged from its original development in the 1920’s. However, the interests of the users of Alberta Park have changed extremely. At this time we find Alberta Park as a park with high usage by children, while maintaining a passive character of walking and picnicking.”

In the 1920s and 1930s, the park was a kind of every-person’s backyard, where the community went in family units to picnic, play, celebrate, appreciate the plantings. By the 1970s, the car was much more a fixture of family life. Plus, the demographics of the neighborhood were changing and spending leisure time in a park as a family unit was no longer a high priority. The park was for young people.

As part of the 1972 master planning effort, 1,800 surveys were mailed to homes in a radius of six blocks from the park. The 182 replies that were returned ranked park needs, and 44 percent of the respondents raised concerns about park safety.

Drawing on the survey results, the 1972 Alberta Park Master Plan called for a new set of priorities, including adding a covered and lighted basketball shelter ($73,000); installation of tot play equipment ($2,000); paving of the existing gravel paths ($3,000); and resurfacing of the tennis courts ($2,000). These improvements were carried out over the following years as funds were available.

The park continues to be a community fixture: the sounds of pick-up basketball games can be heard on weekends and evenings; the upgraded playground structures filled with youngsters; and come spring the timeless sounds of baseball.