Six glass plate negatives from 1908 retrieved from the basement of the von Homeyer house in Northeast Portland tell a story about a setting, home and family life that have become extinct but not forgotten.

The first von Homeyer house in northeast Portland at 850 Going Street (today’s NE 27th and Going), from a glass plate negative. Hans O.S. von Homeyer on the roof with sons Hans W.S., and Irvin Erwin Frederick. At the back steps: Minnie and daughter Gretchen. View looking toward the northwest, about 1908.

The glass plates are some of the thousands of photos unearthed by new owners Michael and Jaylen Schmitt earlier this year as they prepared the house for overhaul and adaptive reuse. This winter and spring, we helped the Schmitts sort, organize and add context to the mountain of photos and documents that had accumulated in the house over the last century.

In May after careful review of each image, we sent more than 30 pounds of old photos “home” to the next generation of family members who had never seen many of these long-passed great aunts, uncles, grandparents and family scenes. Duplicates and some others (including the glass plates) went to an estate sale that helped clear out the house in May. A select few of the photos and documents will remain behind with the house going forward.

But these six are special, because they are so old and fragile, and because after some detective work, we now know what they depict.

The first time we saw them this winter, we knew they might be some of the most interesting images in the entire collection: they showed a young family’s connection with an old house–something always near to our hearts.

The von Homeyers at 850 Going: Erwin and Hans at left; Hans, Minnie and Gretchen on the front porch. Looking southwest about 1908.

They showed wide open spaces around the house, hinting at things to come.

The von Homeyers at 850 Going: Hans, Hans and Erwin on the porch; Minnie and Gretchen at the side. No sidewalks, dirt streets and wide open lots all around. Looking east-southeast about 1908.

They showed the home’s interior, three children in the foreground, columns and windows behind.

Gretchen, Hans and Erwin at the bay window, 850 Going Street, about 1908.

And they showed a builder at work upstairs. The backlighting from the second floor window makes it difficult to see, but the carpenter’s square, saw and plane behind him, hammer in hand, and the at-work stance of the human subject, come through clearly.

Hans von Homeyer at work, upstairs at 850 Going, about 1908.

As glass plate negatives go, they are a tad hard to read if you just pick them up for a quick look. Thick with emulsion, it takes a lot of light to reveal the negative image. Which might be one of the reasons why they survived the estate sale: people couldn’t tell what they were seeing.

We made prints and stared at them for a long time. Where is this place, we wondered.

Over the winter, as we continued looking at hundreds of family photos and began to recognize particular people and places, and as we researched the von Homeyer family story, a common thread began to tie some pieces together: this house.

First, we found this paper image in one of the old photo albums. It’s a “Real Photo” postcard showing two generations of a family out front of a tidy house.

This Real Photo postcard was sent from Hans to brother-in-law Karl Tripp about 1909, looking southwest. Minnie and Gretchen at left; Hans center with Hans and Erwin; two unknown visitors. A few more nearby houses and a new coat of paint.

The glass negatives show a slightly earlier version of the house, before paint, less landscaped, a little rough around the edges, but definitely the same place. By 1909 and the postcard to Karl, the von Homeyer home at 850 Going was looking pretty tidy.

Do-it-yourself cards like this were first offered by Kodak in 1903 and almost immediately blew up in popularity as friends and families exchanged their own photos and brief greetings through the postal mail. An early and s l o w version of sharing photos and a few well chosen words across distance. Something families still like to do today. Here’s more about how Real Photo postcards transformed photography between 1905-1915.

This one was sent by the first Hans O.S. von Homeyer (1871-1942), father of Hans W.S. von Homeyer (1898-1969) who built the house at NE 24th and Mason, grandfather of the brothers Karl and Hans E. von Homeyer (1927-2002) who lived in the Mason Street house all their lives. Hans the elder sent the card to his brother-in-law Karl in Chicago, Minnie’s brother. The message on the back was in German which we can’t read, so we sent a picture of the almost undecipherable longhand script to our friends Christiane and Roland in Germany for quick translation. They wrote back immediately with the 110-plus year-old postcard greeting that made us smile:

“Dear Karl, we are all still alive and frisky. How are you? With best greetings from all of us to all of you.”

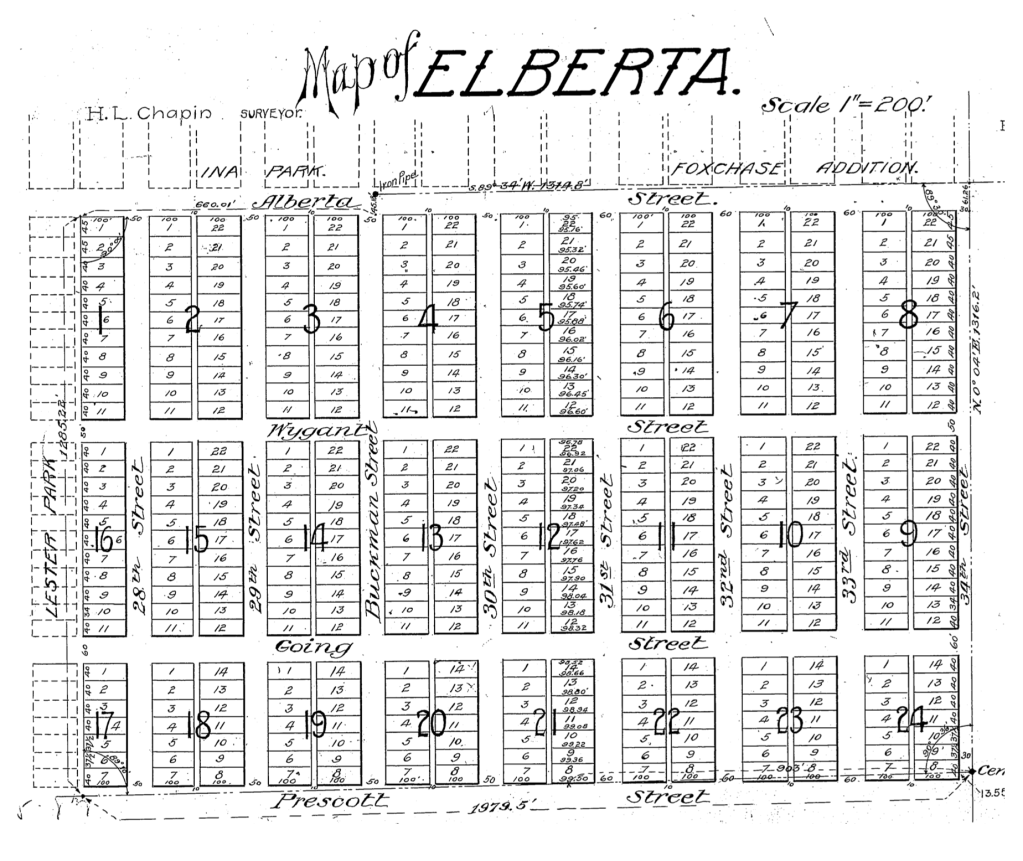

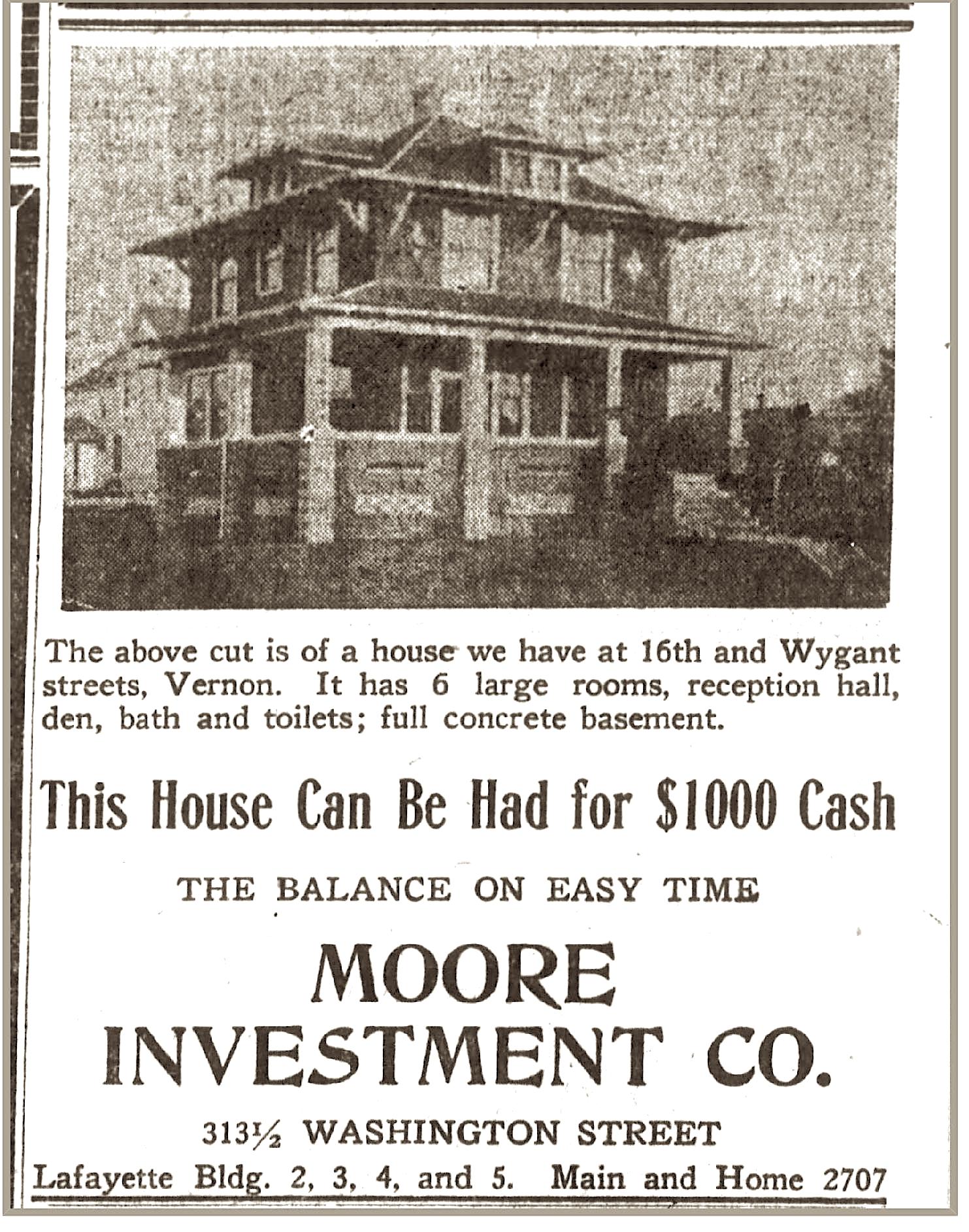

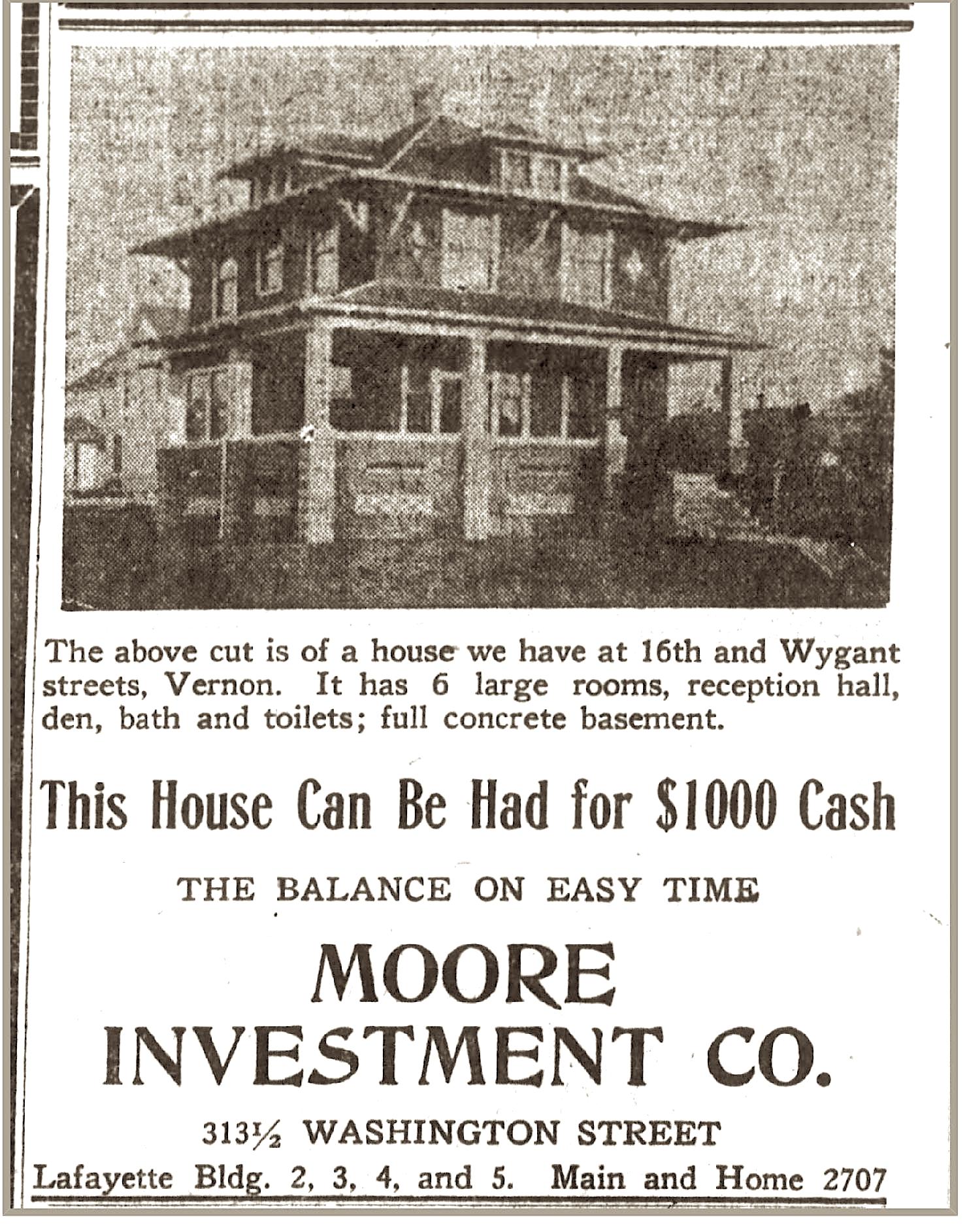

The card was signed “H. von Homeyer, 850 Going Street, Portland, Ore.” which of course also piqued our interest, knowing that Going Street makes its long east-west transit through today’s King, Vernon, Concordia and Cully neighborhoods. We’ve looked at enough old east-west addresses to know 850 was going to be about 27 blocks east of Martin Luther King Jr. Boulevard and would probably end up in the Elberta Addition.

If you search for that address in pastportland.com (which is one of the very best tools for converting between pre-address change addresses and today) it comes up empty. Plenty of numbers either side, but no 850.

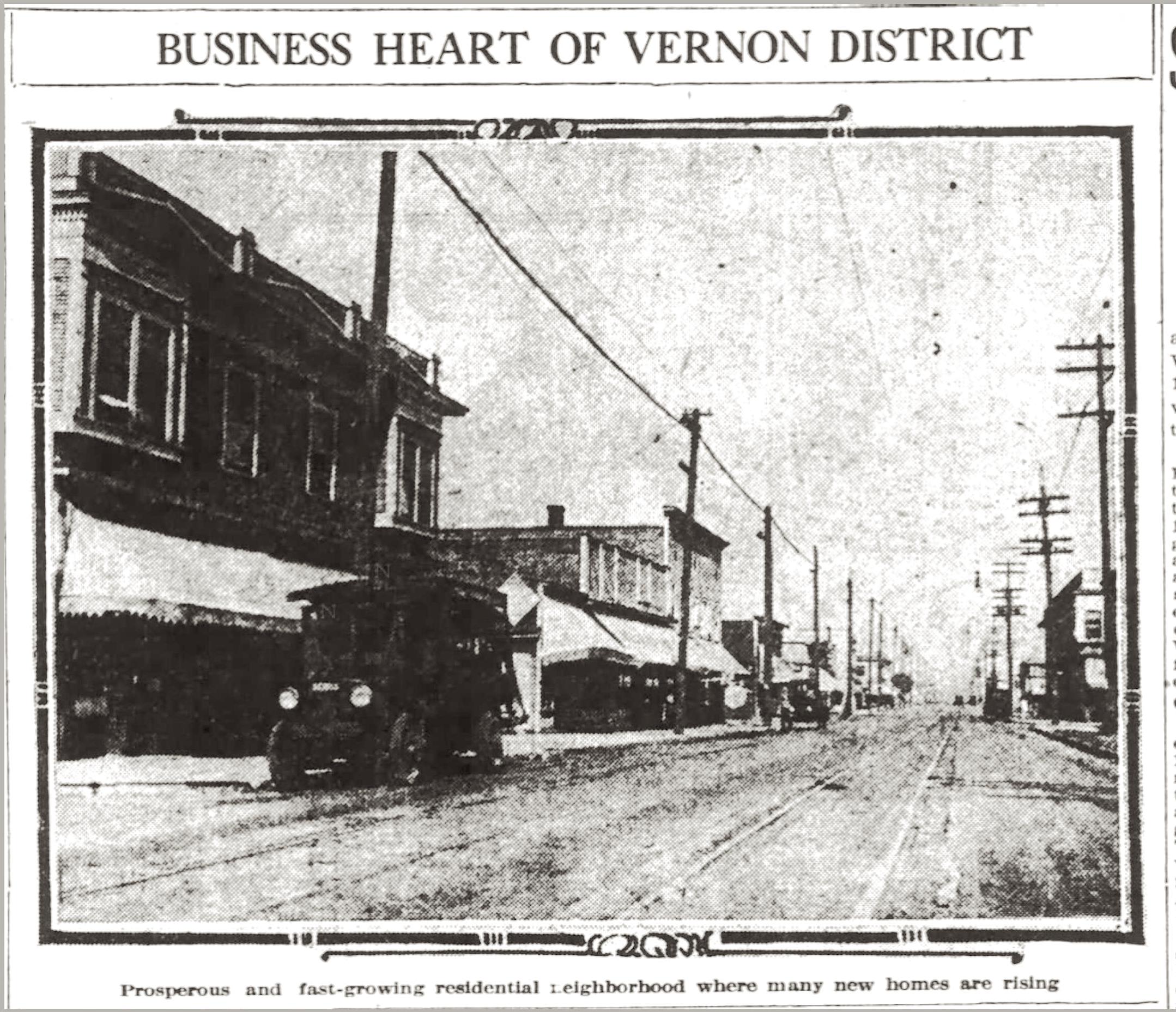

We looked for 850 in the 1909 Sanborn Maps, but this block and several others nearby were still unbuilt brushy vacant lots with dirt roads scratched into the ground. Sanborns were used by fire insurance underwriters to gauge fire risk based on the presence of fire hydrants, distance from fire stations and types of construction materials and heating systems used by various buildings. But out near 27th and Going in 1909, there weren’t any buildings that needed insurance underwriting. So, it wasn’t mapped.

Next we began nosing around The Oregonian and the Oregon Journal, both of which are searchable by word going way back if you have a library card. News stories, letters to the editor from Hans and other mentions began turning up, confirming the von Homeyer’s presence there.

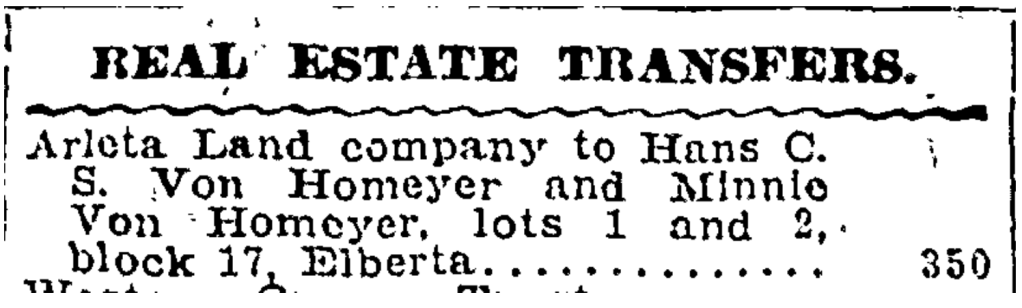

Then we found this buried in the real estate transaction list: Hans and Minnie buying a vacant lot in the Elberta Addition for $350 in late July 1907.

From The Oregonian, July 29, 1907

That gave us a lot and block number and a place to look. So we downloaded the Elberta plat from the Multnomah County Surveyor’s office, and began trial-and-error looking on Portlandmaps.com for block and lot details in that vicinity. We quickly found lots 1 & 2 of Block 17 today–the northeast corner of 27th and Going–but the pre-address-change address for that place says 848 and what’s there today doesn’t look anything like the postcard.

We began to note that after 1910, all references to 850 Going stop. Going, going gone. So how come 850 shows up in some news stories and on the postcard, but then disappears? We had a hunch.

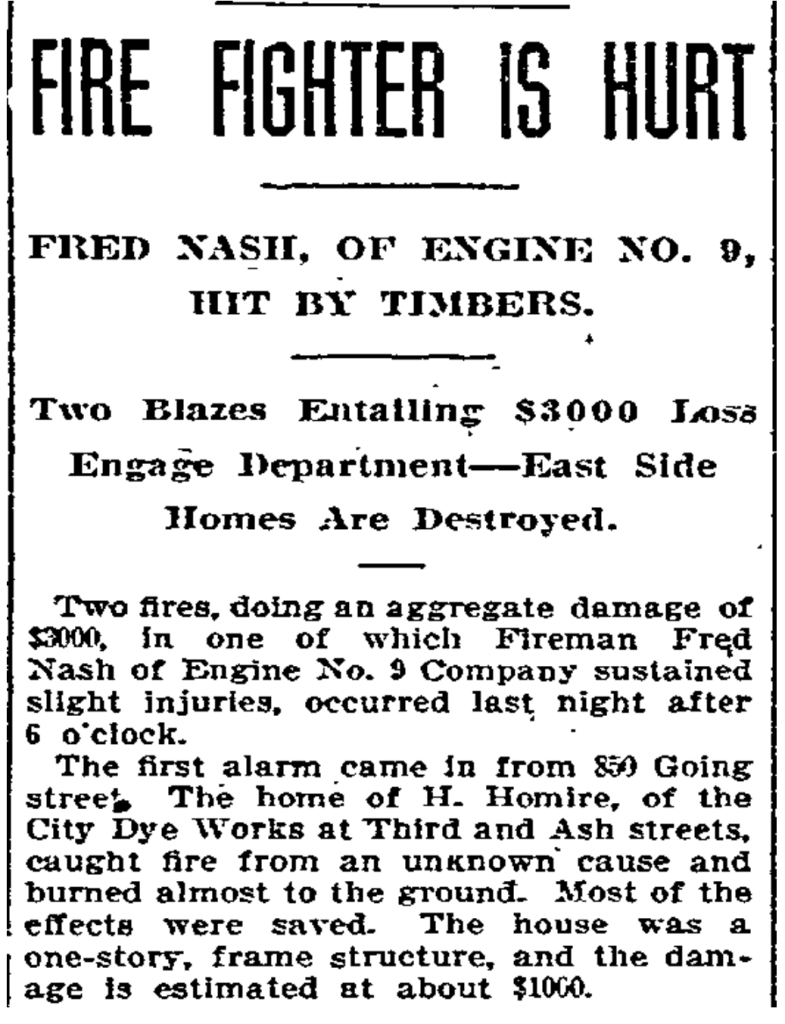

The next newspaper story we found made it clear:

From The Oregonian, September 20, 1909. Creative spelling.

Glancing back and forth between the post card picture and the glass plates, with the fire story in mind, the realization struck: the images on the old glass and the postcard print were showing the same house: the first von Homeyer home, built in 1907 after they arrived in Portland from Chicago. In September 1909, it burned to the ground.

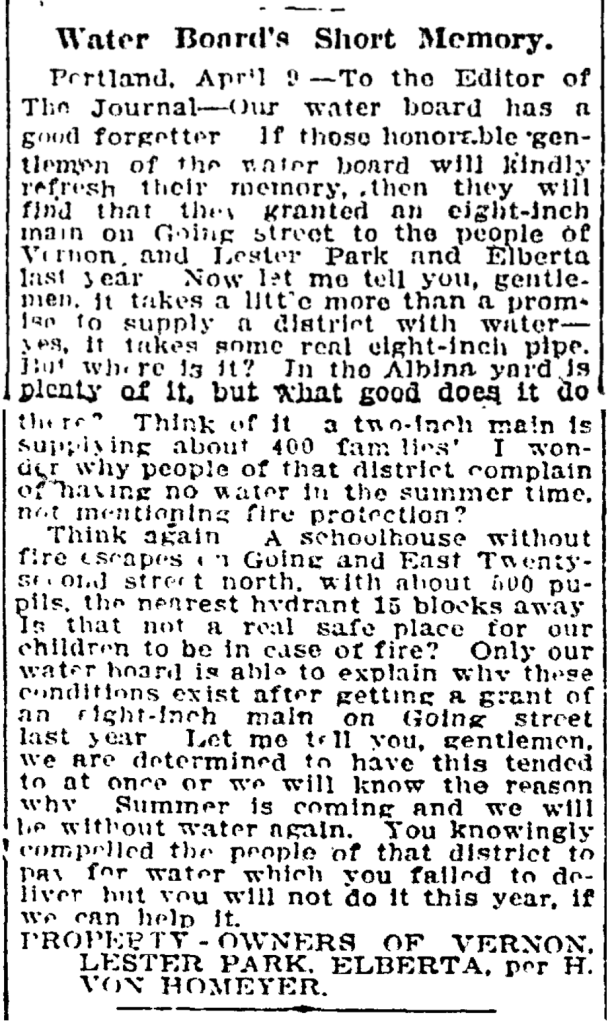

Eerily, Hans von Homeyer foreshadowed what might happen to their new home on Going Street. In a letter to the editor of the Oregon Journal the year before, signed on behalf of area residents, Hans gave voice to frustrations with the city about lack of water pressure in their part of the neighborhood, and worries about the fire safety of the huge wood-frame Vernon School just up the street, where their children attended.

From the Oregon Journal, April 13, 1908

In June 1911, Hans and Minnie sold Going Street and took up residence in a spacious Craftsman-style house on NE San Rafael just east of today’s Martin Luther King Jr. Boulevard. The kids were growing and so was their business. Later, the von Homeyers moved to Vancouver where their story continued.

Have a good look at the 1908 surroundings as you think about the corner of NE 27th and Going today. Just across the street is the former dry goods store. The streets were unpaved gravel, no curbs or sidewalks until 1913. On the property where the von Homeyer house stood, a new home was built: the late Queen Anne Victorian that stands today, known as the Going Queen. Today, that intersection is all concrete streets and sidewalks, topography leveled off, no vacant lots in sight.

Aside from the small miracle of their basic survival all these years is the reality these glass plate negatives somehow made it through the fire or were carried out of the burning house they depict: the news story reported “most of the effects were saved.”

For extra credit, the six glass plates also made it through the estate sale in May. No one was interested in them, so after the sale they made it to the dregs pile that Michael was going to have to deal with one way or another. When we learned this, we very happily rescued them from the dregs. Now they’re in a safe place.

The last of the six glass plates–smaller in size, made a little bit later in a different location–may be the most wonderful, showing youngest sister Marguerita Anna “Gretchen” von Homeyer on a porch, bow in her hair, standing near an ivy-covered column, looking off toward the future. Probably taken in about 1913. She was eight years old.

Marguerita Anna “Gretchen” von Homeyer about 1913.