With many of us home for a while—as life slows down in deference to the social distancing required to reduce spread of the coronavirus—we’re taking stock of just how many interesting blog posts we have on the drawing board, from the history of the Vernon Standpipe to some incredible photos from our history friend Norm Gholston to three new profiles of neighborhood builders and more. Might just as well make good use of this time, right?

But before we do that, it’s appropriate and necessary to make note of this unusual moment in our world (and in the neighborhood) in the midst of a global pandemic. For the record, in March 2020 Portland has come to a stop: schools closed, sports leagues cancelled, workplaces shuttered or greatly limited. Empty grocery store shelves signal our collective desire to get ready for what feels like the leading edge of a slow-moving blizzard about to descend for a while on our city, state, country and beyond. The rhythms of our day-to-day lives now feel uncertain.

Because we often like to look back as a way of seeing our way forward, we’ve been reading news coverage of the 1918 flu pandemic when it descended on Portland. We thought you might be interested in seeing a few clips.

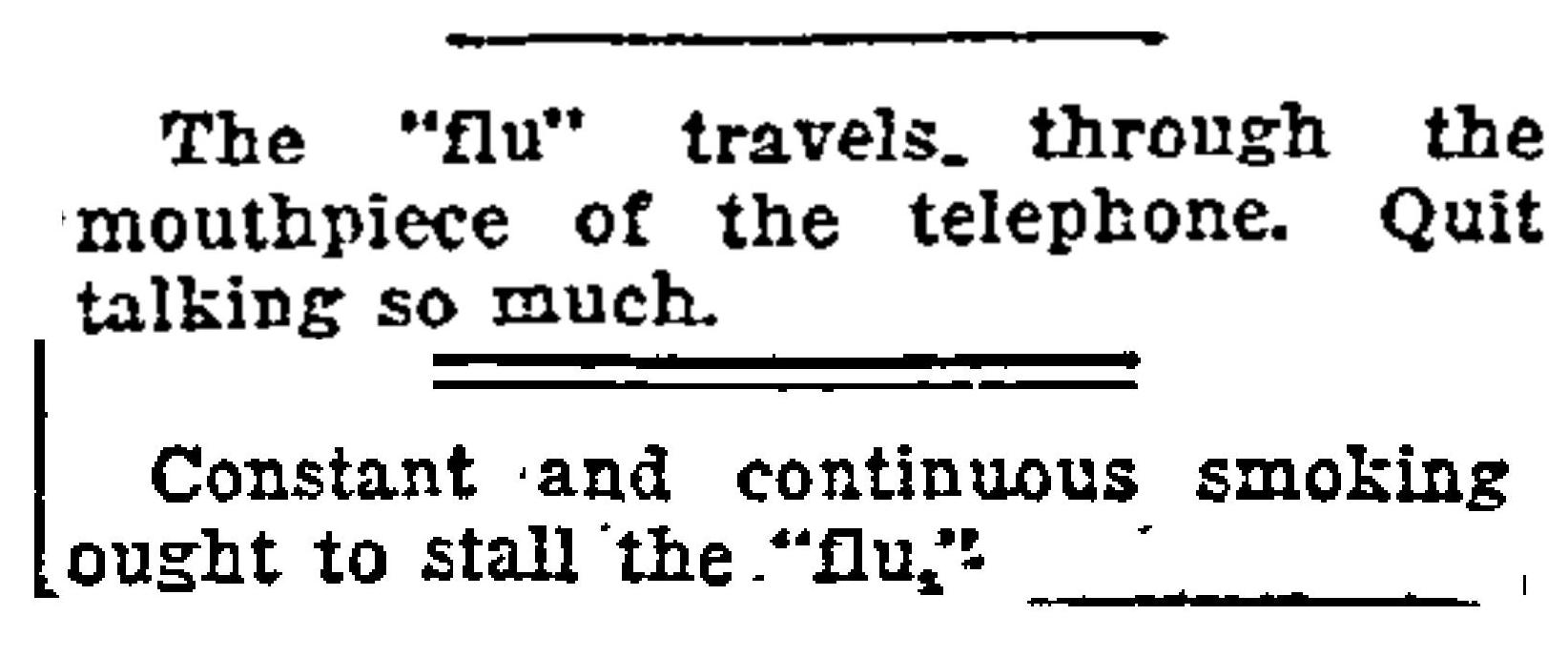

The first mention in the papers in early October 1918 was a simple sentence buried on an inside page: “Seattle thinks it is getting the flu.” At first, the news percolated in conversation and people weren’t sure what to make of it. Jokes were made in small talk:

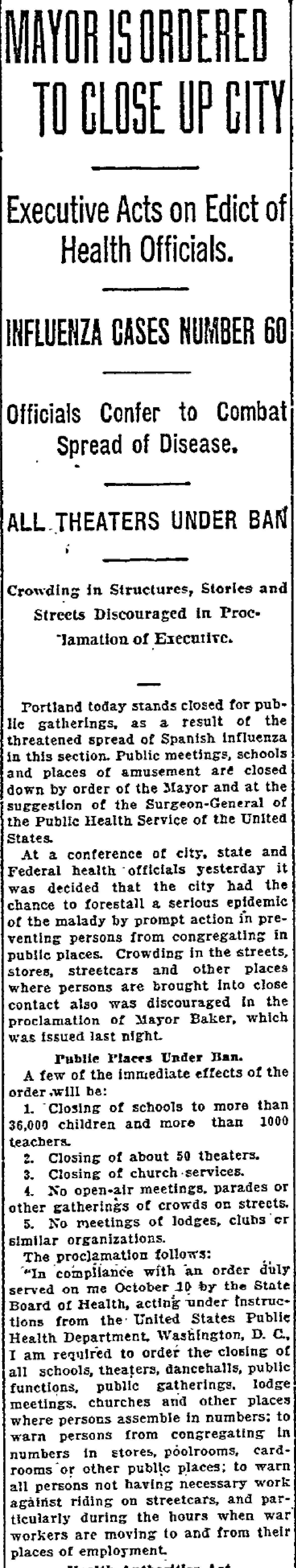

But on October 10th, Portland Mayor George Baker implemented an order that required downtown businesses to close by late afternoon each day, and completely closed “schools, churches, lodges, public places of meetings, and places of amusement.”

From The Oregonian, October 11, 1918

Needless to say, this was very unpopular and most of the ink we saw in local papers was about the disruption to sporting events. Tensions in the community as people sought “social distance” were captured by W.E. Hill, an artist for The Oregonian who captured this scene on a streetcar in late October 1918. The caption reads: “With all this Spanish influenza around, it was not time for the delivery boy at the other end of the car to choke on a chocolate almond and start coughing.”

From The Oregonian, October 25, 1918

A near daily recitation followed in November about the number of new cases diagnosed, and the number of deaths, with victims and addresses named. Auditoriums and gyms were converted to makeshift hospitals. Coos Bay ran out of coffins.

From The Oregonian, October 24, 1918

But by mid-November–more than a month after Baker’s complete shutdown–the ban was lifted and life seemed to get back to “normal.”

From The Oregonian, November 17, 1918

There were false starts with plenty of ups and downs–and more deaths–as localized outbreaks continued to be reported through November and December and into the new year. This article from December 1918 indicates school was back in session and the city had progressed to locally specific quarantines when cases of the flu were diagnosed. Signs were put up on individual homes.

From The Oregon Daily Journal, December 12, 1918

It was well into 1919 before local newspapers stopped writing about the flu on a daily basis and the former rhythms of life in Portland resumed.

We know the 2020 outbreak is its own thing and the world has changed in the last 100 years. We’re making history right now, which is an unpredictable business. There’s solace, we guess, in knowing our homes and neighborhoods have endured these uncertainties before, and that spring and warmth (despite this morning’s snowfall) are right around the corner.

Now, back to the life of old buildings and neighborhoods. Stay tuned.